3 Leaning into difference to respond to catastrophic bushfires

Jessica K Weir[1]

Abstract

The presence of catastrophic bushfires (wildfires) is escalating with climate change, and societal debates have shifted to consider the contribution of Indigenous peoples’ fire leadership. These debates, however, are constrained by very different worldviews about what nature even is, and, then, who has expertise about it. Miscommunication is rife, and so too is discrimination. This chapter unpacks these debates to help find more respectful terms, and, then, facilitate meaningful connection and action. Whilst the focus is often on different burning techniques to reduce flammable materials in the landscape, this analysis foregrounds the intention behind different burning traditions and how this relates to understanding the bushfire risk faced by both humans and nature.

Keywords

Indigenous rights; bushfire risk; natural hazards; cultural burning; discrimination; public sector; expert evidence; geography

Introduction

Thinking deeply about the different ways different people understand what nature even is may seem a world away from protecting ourselves from catastrophic bushfires (or wildfires), but this is exactly what Indigenous leaders have been saying over and over again (Pettersen 2021; Steffensen 2020). This communication, however, is often missed by those who are unfamiliar with Indigenous peoples’ knowledge traditions, in part because the same words are being used but with different meanings. As a white, non-Indigenous scholar, I have learnt that much is lost in the miscommunication. Instead, by leaning into the differences, it has been possible to better hear what is being communicated, whilst building a deeper appreciation of my own perspective, and, then, find opportunities for meaningful connection and action.

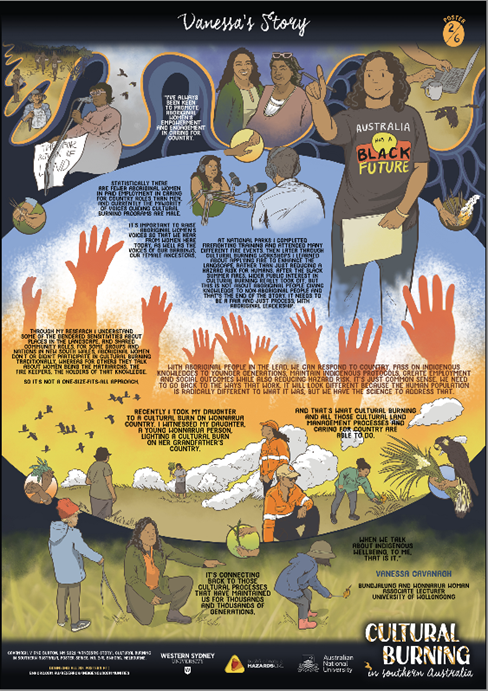

Undeniably, there is fertile intellectual ground in learning from Indigenous peoples’ fire expertise, but there are also far-reaching discriminatory practices working against this expertise. This discrimination needs to be addressed as part of the learning, paying attention to how different expertise sets are resourced and judged as carrying authority. This includes understanding that Indigenous peoples’ expert knowledge about nature arises out of, and is sustained by, their custodial relationships with nature (Graham 2009). Currently, Indigenous leaders spend too much energy arguing for the space to speak, to be taken seriously, and to be supported to enjoy their landscape burning and other traditions – as illustrated in the poster Vanessa’s story (Figure 1).

Catastrophic fire

In the 2019-2020 spring and summer, catastrophic bushfires along the east coast of Australia became the global symbol of climate change loss, generating intense debate about why this was happening and how it might be avoided in future. Many debates centred on Indigenous peoples’ landscape burning practices. Could this burning expertise help reduce the destructive reach of catastrophic bushfires in the future?

When the British Empire arrived on this continent it encountered park-like lands that Indigenous people had cared for by regularly lighting small fires, now known as cool burns or cultural burns (Pascoe 2014). As the colonial powers attacked Indigenous peoples’ societies and seized their territories, these cool fires were suppressed and thick flammable scrub became prolific and has remained so. Climate change is now escalating the risks associated with this flammable landscape.

But what was specifically being asked of Indigenous peoples’ landscape burning practices during the catastrophic bushfires? I think there were two propositions. First, whether Indigenous burning could be added to the suite of government approaches to bushfire risk as a discrete burning practice. Or, second, whether Indigenous fire leadership could help re-think the government’s approach to bushfire risk itself. Either way, both propositions require grappling with the different meanings and assumptions that Indigenous fire leaders bring to their landscape burns.

Unpacking difference

Indigenous fire practitioners have explained that there are multiple reasons for lighting landscape fires as part of holistic approaches to care for and with Country – an Indigenous word for hearth, home and territory (Cavanagh 2022; Pettersen 2021; Steffensen 2020; Williamson 2022). By regularly lighting cool burns to reduce thick bushes, bark, grasses and leaf litter, the frequency and intensity of large bushfires are reduced (Fletcher et al. 2021). This protects the canopy, which is destroyed in large bushfires, and also nurtures plants that need fire, such as seedpods that require smoke to open. After the burns, game for hunting is attracted to the new green growth, and it is easier to walk through the landscape (Garde et al. 2009). The burns are an opportunity to teach and practice law, ceremony and song, as passed down from ancestors and ancestral creators (Brown 2021). This governance approach is a reciprocal relationality of life with all species, landscape features, the sky, stars and more (Tynan 2020; Pascoe et al. 2024). It is both an expertise and worldview, which is taught through stories about the importance of humility and respecting Country (Bodkins et al. 2016).

In comparison, the traditional government approach to landscape burning is an almost singular focus on bushfire risk – to reduce the thick bushes, bark, grasses and leaf litter because they are so flammable (Morgan et al. 2000). These are called hazard reduction burns and are stereotyped as ‘making the ground black’. Their purpose is to protect people and assets. They are primarily conducted along the edge of towns and cities, and are authorised by wildfire science expertise about bushfire likelihood and behaviour (Leavesley, Wouters and Thornton 2020). Instead of an all-encompassing relationality of life, the environment is considered an asset for protection in hazard reduction burns, such as a watershed for a dam or a threatened species. For example, during the catastrophic bushfires, fire agencies protected the very rare Wollemi pine trees that date back to the time of dinosaurs. Criticism about the singular focus of hazard reduction burns has led to government experiments with cool burns for ecological purposes (Weir 2023). This is informed by ecological science expertise about the genetic, species and habitat diversity of ecological life.

Clearly, the different purposes of these landscape burns are fundamentally influenced by their different worldviews and expertise sets. The hazard reduction and ecological burns are supported by natural science expertise and the accompanying worldview of a nature separate to society. The natural sciences seek to observe and describe this nature as objectively as possible by minimising politics, culture and values in the observational method. In comparison, the Indigenous worldview and expertise holds nature with society as co-constituted forms. Indigenous people describe themselves as coming from Country, which is also where their expert knowledge comes from and is maintained. And it is not just humans who have society, but nature has society too: lively worlds with culture and language, of which humans are a part (Tynan 2020). Instead of separating out nature and society for study and analysis, as represented in the orthodox natural and social science traditions, the focus is on relationships: which relationships are important, why, and what might be done in response. Thus, whilst wind and weather are important factors in the two different expert knowledge traditions, in the Indigenous approach these elements are observed as part of custodial ethics to nurture the ethical relationality of life.

There is considerable interest in the different techniques – the Indigenous landscape burns are smaller, cooler, and more frequent, whilst the government hazard reduction burns are larger, hotter and focused on protecting places where people live; however, this chapter foregrounds the intention behind these burning practices. The Indigenous burning approach arises out of inter-generational custodial ethics that understand human lives as lived within and with nature through ethical relationships of mutual co-dependency. Whereas the hazard reduction approach is about protecting values important to people from a powerful and dangerous nature. It might not seem like an important difference, but it is an ordering of what matters, and what might be done about it, as discussed further below.

Understanding the logics and authority of Indigenous peoples’ fire expertise is, however, thwarted by discriminatory knowledge politics. The natural sciences are judged as being the more objective knowledge set and thus closer to truly knowing this assumed separate nature. The corollary is that all other expertise sets only have subjective expertise about nature because they do not have the natural science methodology. Indigenous peoples’ expertise is cast as a less authoritative cultural contribution. Bringing these two knowledge sets onto less discriminatory terms is challenged by the assumption that a separate terrestrial nature really does exist, even though it does not (Ellis et al. 2021). Instead, it is a naming of reality that co-evolved with the natural sciences (Robin 2018).

Addressing discrimination

In that terrifying moment when it felt like the whole of Australia was ablaze, it also seemed possible that this extreme experience combined with societal interest in Indigenous fire leadership might catalyse a broader national reckoning to respect Indigenous peoples’ fire leadership. Unfortunately, that conversation was abruptly cut short by the March 2020 COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns. Who knows what might have happened without this truncation? Indigenous peoples’ fire leadership has remained on the agenda of bushfire agencies, albeit largely couched within the terms of supporting a cultural practice (Williamson 2022). This is the first and less ambitious proposition I introduced earlier.

In addition to nature, the term culture also needs consideration to address both miscommunication and discrimination. Culture is used by Indigenous leaders to signal that they are saying something different to the government, and that it is from their culture, as with cultural burns. Yet, this strategy risks compounding the discriminatory view that Indigenous fire leadership is a cultural contribution to the assumed normal and objective government approach based on the natural sciences. Further, it is not just knowledge politics to contend with here, but also the racial discrimination and violence wrought by imperialism. Globally, imperial and colonial powers rationalised their seizure of Indigenous territories by arguing they brought a superior civilization with superior expert knowledge (Pascoe 2014). This has continued in settler-colonial public policy, with its language of care for those whom it has dispossessed (Strakosch 2024). Indeed, not expected to be part of modern Australia, Indigenous peoples’ presence was still being included as ‘The Past’ in bushfire inquiries until recently (Williamson et al. 2020: 13-15).

As government and academic institutions increasingly engage with Indigenous peoples’ fire expertise, it has become apparent that addressing the legacies of discrimination are inherent to any collaborative approach (Pascoe et al. 2024). This involves both identifying and overturning their own discriminatory practices, and supporting Indigenous peoples’ self-determination to practice their laws and teach their culture (Hoffman et al. 2022). Currently, non-Indigenous people form some 96% of the population of Australia; Indigenous peoples are marginalised and their authority invalidated in a democratic system based on majority rule, with a taxation system funding a very different bushfire risk mitigation approach. The 2023 failure of the constitutional referendum to recognise an Indigenous Voice to Parliament compels the urgency of this work within the public sector and universities (Behrendt 2024).

Re-thinking and re-purposing risk together

During the catastrophic bushfires, cultural burns in southeast Australia made headlines for saving property in multiple locations, but this should not distract from the broader communication at hand. Indigenous fire leadership is more than a burning method. It is a transformative agenda with powerful logics for action, that are laws held by Indigenous peoples across the continent. Backing Indigenous leadership can absolutely mobilise a re-think of Australia’s bushfire risk onto broader and more connected terms. Lives lived in ethical relation is a paradigm shift in who we are and where we are, and what we know, and how we know it.

Traditionally, the bushfire risk priorities of the emergency management agencies are to protect people, and then property, with the environment a distant third. In this assumption the environment is not Country but ecological assets – such as threatened species. However, Indigenous leadership turns this ordering of risk priorities on its head: Country comes first, and people and property are protected within that. This is not to disregard people and property, but to understand that they are looked after within Country (Steffensen cited in Weir 2020).

Here I present two critical contributions as consequential for re-thinking risk. First, the holding of nature with society as both/and, rather than either/or, means taking lives lived in connection very seriously. Nature is not a separate place to visit, protect or neglect, but life forces within which are own lives are held. A double movement is required to move away from nature as separate – return people to nature, and return nature to its cultural and ethical domains (Plumwood 2002). To do the former without the latter is to constrain nature to energy flows rather than embracing relational accountability.

For bushfire agencies and academics to join a re-thinking risk conversation with Indigenous leaders, a double movement is required to reposition humans and nature in relation to each other. First, to return people to nature, and, second, to return nature to its cultural and ethical domains (Plumwood 2002). To do the former without the latter is to constrain nature to energy flows, rather than embracing the ethical relationality of all life and culture. Nature is not a separate place to protect or neglect, but lively life forces, ways of knowing and being, within which are own lives are held. This double movement also has consequences for understanding Indigenous peoples’ expert knowledge about nature, to value its logics of investigating what is (observational expertise) together with what will be (ethical expertise) (Graham 2009). This holistic expertise has much broader reach than bushfire risk mitigation as land management (Marks-Block and Tripp 2021). It articulates the immediacy of all that is at stake whilst charging everyone with responsibilities to do something about it.

Catastrophic fires are a dramatic experience of climate change and our embedded lives together. There is much traction for bushfire agencies and bushfire academics to learn from Indigenous leadership, yet it also requires power sharing: addressing discrimination and respecting the presence of another authority. Indigenous peoples’ fire expertise is embedded in Country and cannot be transferred to the public sector and universities in a briefing, workshop, project or book. It needs to be supported through Indigenous peoples’ own institutions. If you are motivated to support this shift, there are many actions you can take for change:

- Prioritise respectful intercultural communication by building your own capacity and the capacity of others, including through education and research

- Address knowledge discrimination by supporting more resources for Indigenous peoples’ expert knowledge institutions, including the return of land

- Create space for Indigenous leadership rather than presenting Indigenous people the false choice of fitting in with the mainstream or being excluded, including tax reform to fund Indigenous peoples’ governance

- Amplify Indigenous leadership in national and international forums

Acknowledgements

I thank my Indigenous and non-Indigenous colleagues who have supported this cultural burning research, and the funders of the Bushfires and Natural Hazards Cooperative Research Centre. I thank the editors and peer reviewers for their support in bringing this chapter to publication. All errors and omissions remain my responsibility.

SDG Alignment

First Nations knowledges and practices have much to contribute to the global UN SDG 2030 agenda and there is an acknowledged critique of this current lack of explicit recognition and referencing. Global discussions are underway to consider how the next set of goals amend this.

SDG 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities

Target 11.4

Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage

SDG 13 – Climate Action

SDG 15- Life on Land

SDG 16 – Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

Target 16.7

Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels

References

Behrendt, L., 2024. Country beyond “no.” ARENA, 19(Spring): 29-32).

Bodkin-Andrews G, Bodkin AF, Andrews UG, Whittaker A (2016) Mudjil’Dya’Djurali Dabuwa’Wurrata (How the White Waratah Became Red): D’harawal storytelling and welcome to country “controversies.” Alternat Int J Indig Peoples 12(5):480–497

Brown, A. 2021. Adrian’s story. In J. K. Weir, D. Freeman, and B. Williamson, editors. Cultural burning in Southern Australia. Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, Melbourne, Australia.

Cavanagh, V. 2021. Vanessa’s story. In J. K. Weir, D. Freeman, and B. Williamson, editors. Cultural burning in Southern Australia. Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Cavanagh, V. 2022. The (re)emergence of Aboriginal women and cultural burning in New South Wales, Australia. Global Application of Prescribed Fire. CSIRO, Canberra.

Fletcher, M.-S., A. Romano, S. Connor, M. Mariani, and S. Y. Maezumi. 2021. Catastrophic bushfires, Indigenous fire knowledge and reframing science in southeast Australia. Fire 4 (61):1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire4030061

Ellis, E.C., Gauthier, N., Klein Goldewijk, K., Bliege Bird, R., Boivin, N., Díaz, S., Fuller, D.Q., Gill, J.L., Kaplan, J.O., Kingston, N., Locke, H., McMichael, C.N.H., Ranco, D., Rick, T.C., Shaw, M.R., Stephens, L., Svenning, J.-C., Watson, J.E.M., 2021. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2023483118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023483118

Garde M, Nadjamerrek BL, Kolkkiwarra M, Kalarriya J, Djandomerr J, Birriyabirriya B, Bilindja R, Kubarkku M & Biless P (2009). The language of fire: seasonality, resources and landscape burning on the Arnhem Land Plateau. In: Russell-Smith J, Whitehead P & Cooke P (eds), Culture, ecologyecology, and economy of fire management in north Australian savannas: rekindling the Wurrk tradition, CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, 85–165.

Graham, M. (2009). Some thoughts about the philosophical underpinnings of Aboriginal worldviews. Australian Humanities Review, 45, 181–194.

Hoffman, K.M., Christianson, A.C., Dickson-Hoyle, S., Copes-Gerbitz, K., Nikolakis, W., Diabo, D.A., McLeod, R., Michell, H.J., Mamun, A.A., Zahara, A., Mauro, N., Gilchrist, J., Ross, R.M., Daniels, L.D., 2022. The right to burn: barriers and opportunities for Indigenous-led fire stewardship in Canada. FACETS 7, 464–481. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0062

Leavesley, A M. Wouters, and R. Thornton, editors. 2020. Prescribed burning in Australasia: the science, practice and politics of burning the bush. AFAC, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Marks-Block, T., and W. Tripp. 2021. Facilitating prescribed fire in Northern California through Indigenous governance and interagency partnerships. Fire 4(37):1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire4030037

Morgan, G.W., Tolhurst, K.G., Poynter, M.W., Cooper, N., McGuffog, T., Ryan, R., Wouters, M.A., Stephens, N., Black, P., Sheehan, D., Leeson, P., Whight, S., Davey, S.M., 2020. Prescribed burning in south-eastern Australia: history and future directions. Australian Forestry 83, 4–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049158.2020.1739883

Pascoe, B. 2014. Dark Emu, Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident. Broome: Magabala Books.

Pascoe, J., Shanks, M., Pascoe, B., Clarke, J., Goolmeer, T., Moggridge, B., Williamson, B., Miller, M., Costello, O., Fletcher, M., 2024a. Lighting a pathway: Our obligation to culture and Country. Eco Management Restoration 24, 153–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/emr.12592

Pettersen, C. 2021. Carol’s story. In J. K. Weir, D. Freeman, and B. Williamson, editors. Cultural burning in Southern Australia. Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Plumwood, V. (2002). Decolonising Relationships with Nature. PAN: Philosophy Activism Nature, 2, 7–30.

Robin, L. 2018. Environmental humanities and climate change: understanding humans geologically and other life forms ethically. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 9(1):1-18. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.499

Steffensen, V. 2020. Fire Country: How Indigenous fire management could help save Australia, Hardie Grant Travel: Richmond, Victoria.

Strakosch, E., 2024. Violence as care: Indigenous policy and settler colonialism, in: Lightfoot, S., Maddison, S. (Eds.), Handbook of Indigenous Public Policy. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 18–34. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800377011.00007

Tynan, L. 2020. Thesis as kin: living relationality with research. AlterNative: an International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 16 (3):163-170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180120948270

Weir, JK. 2023 Expert knowledge, collaborative concepts, and universal nature: naming the place of Indigenous knowledge within a public-sector cultural burning program, Ecology and Society 28(1):17 https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-13822-280117

Weir, J. K. 2020. Bushfire lessons from cultural burns. Australian Journal of Emergency Management 35(3):11-12.

Williamson, B. (2022) Cultural burning and public forests: convergences and divergences between Aboriginal groups and forest management in south-eastern Australia, Australian Forestry, 85:1, 1-5, DOI: 10.1080/00049158.2022.2054134

Williamson, B., F. Markham, and J. K. Weir. 2020. Aboriginal peoples and the response to the 2019-2020 bushfires. Working Paper No. 134/2020. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, Canberra.

How to Cite this Chapter

Weir, J. S. (2025). Leaning into difference to respond to catastrophic bushfires. In Boddington, E., Chandran, B., Dollin, J., Har, J. W., Hayes, K., Kofod, C., Salisbury, F., & Walton, L. (Eds.). Sustainable development without borders: Western Sydney University to the World (2025 ed.). Sydney: Western Sydney University. Available from https://doi.org/10.61588/TESB2263

Attribution

Leaning into difference to respond to catastrophic bushfires by A/Prof Jessica Weir is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical 4.0 International https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

- Jessica Weir, Western Sydney University, Institute for Culture and Society, Australia ↵