4 Redrawing the Circular Economy: Organic Waste and Peri-Urban Futures

Stephen Healy[1], and Abby Mellick Lopes[2]

Abstract

This paper examines the circular economy’s application in addressing sustainability challenges, focusing on organic waste and peri-urban futures. Critically reflecting on the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s definition of circularity, we explore how waste minimization and ecosystem regeneration align with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) like climate action and responsible production. Realising this more ambitious and transformational version of circularity involves us in a process of redrawing the “circle” and in the process reimagining economies. We explored this possibility through a case focused on redirecting organic waste, in particular spent coffee grounds, from urban centres to peri-urban farms.

Using co-design and action research methods, we established a reverse logistics supply chain, highlighting collaborative efforts among social enterprises, family farms, and academic institutions like the University of Technology Sydney. Drawing on Diverse Economies scholarship and George DeMartino’s insights, we advocate for involving diverse economic actors and minimising risks through iterative development. This approach underscores the potential of regenerative practices, including hemp cultivation, to mitigate climate impact and foster sustainable economic linkages.

Keywords

Circular economy; Organic waste; Diverse economies; Regenerative farming

Introduction

The circular economy framework is now widely adopted by governments and the corporate sector as an alternative to the “take-make-waste” approach. Think tanks like the Ellen MacArthur Foundation define circularity as a system where materials never become waste and nature is regenerated, emphasising product life extension, reuse, repair, recycling, and composting (EMF n.d.). Applying circular economy principles can help achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 13 on Climate Action and SDG 12 on Responsible Production and Consumption. This paper argues that circularity can be expanded to address other SDGs, such as ending hunger (SDG 2) and achieving gender equality (SDG 4).

Realising this more ambitious and transformational version of circularity involves us in a process of redrawing the “circle” but also, and in equal measure, reimagining economies. There is a growing recognition of the role of social and cooperative enterprise, as well as social and solidarity economy in developing circular economies and in achieving SDG goals. This speaks to a need to consider the role that more-than market exchange and more-than capitalist enterprise might play in achieving these ambitions.

This chapter is part of the “Investigating Innovative Waste Economies” project, funded by the Australian Research Council. Following Çalışkan and Callon (2009, 2010), the project used a case-based approach to explore various and innovative enterprises in which waste is economised: what organisational efforts are involved in detaching from some forms of waste (single use plastics), reattaching to others (organics), or developing new regimes in governing discarded materials (bulk textiles). We studied these dynamics by following these materials and working with others in Australia already involved in innovative economisation. Through co-design and action research, we redirected organic waste, specifically spent coffee grounds (SCG), from Sydney’s urban centre to its agricultural outskirts. This in-vivo experiment revealed the social, economic, and ecological aspects of a reverse supply chain.

This paper makes two conceptual moves. First, using the Diverse Economies scholarship, we analyse the relationships that enable this chain, expanding the “circle” to include both market and non-market exchanges, and capitalist and non-capitalist actors (Gibson-Graham et al 2013; Hawkins and Healy 2023; Healy and Mellick Lopes 2023). This reverse supply chain creates a “vernacular-circle,” meeting diverse interests (Quirk et al 2024). Second, drawing on the insights of economist George DeMartino (2022) we consider how a reflexive, co-design approach works to minimise risk while pursuing a pathway to innovation. DeMartino calls this a “harm-centric” approach to economics, which allows us to avoid the error of leaping to scale too quickly.

Reverse Logistics, Diverse Economies, different circularities

Our research identified actors who could help transport organic waste, particularly spent coffee grounds and chaff – a by-product of the roasting process – from the Central Business District (CBD) to peri-urban farms. A key figure was Michelle Zeibots, a transport planner and the owner of Hartley Vale Good Garlic Company, a farm 150 km west of Sydney CBD. Since purchasing the 12-acre farm in 2017, Michelle and her family have been growing garlic commercially for wholesale in Sydney. To amend the rocky soil, she started using compost from a Newtown café in the CBD, discovering through windrow composting numerous benefits for soil regeneration.

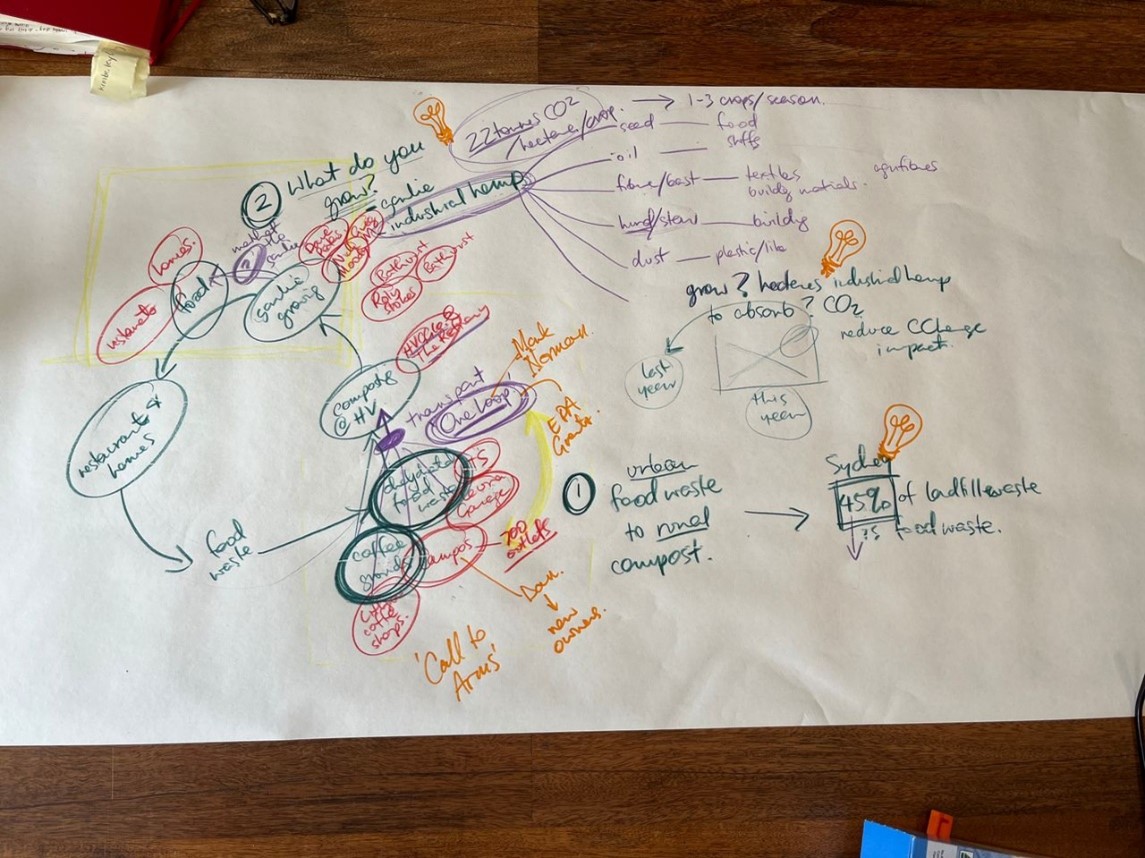

We asked Michelle to map the current economy at her farm—Hartley Vale’s diverse relationships with suppliers, haulers, and consumers. She explained how her family collected coffee grounds from coffee roasters and the University of Technology Sydney, which had industrial-scale food dehydrators to reduce organic waste pickups. Michelle also mentioned other interested cafes and waste haulers, with some connections weakened during the pandemic. The result was a colour-coded diagram showing the relationships, both existing and hoped-for, needed to strengthen her enterprise post-pandemic.

Using Michelle’s map as a guide, we held a collaborative design workshop in December 2022 to create a reverse logistics supply chain for organics. Participants included organic farmers, vermiculturalists, three large-scale coffee roasters, the University of Technology Sydney, local council representatives, City of Sydney officials, and a social enterprise aiding ex-prisoners with waste-hauling employment.

The goal of the workshop was to collaboratively create a circular supply chain, bringing together existing but fragmented efforts. Participants gathered around a four-metre map representing the reverse logistics of food waste—from disposal and gathering to dehydration, transport, and windrow composting. As they discussed and brainstormed problems, the conversation flourished, identifying four enabling conditions.

- Family farms can receive tons of waste for windrow compost as a gift (rather than acting as commercial tippers).

- Social enterprises can haul this waste in a cost-effective way because their mission is employment and training, not profit.

- University of Technology Sydney (UTS), which originally purchased the food dehydrator to minimise waste handling costs, along with disused council land, could act as intermediate sites for the storage and processing of organic waste, and

- Cafes, roasters, and institutions that want to do the right thing, and be seen to do the right thing, can also be enrolled in this system.

| Actor | Family farm | University | Social enterprise | Coffee roasters and cafes |

| Organisation type | non-capitalist

(Family enterprise) |

state supported (not for profit) | “Alternative capitalist” | capitalist firms |

| role in supply chain | reception | client | service provider | client |

| exchange

relationship |

gift | commercial transaction with waste management company | contractual relation to provide service | commercial transaction with WM company |

Table 1: Diverse Economy Reverse Logistic Supply Chain

This story illustrates how different economic logics—gift, rational self-interest, employment, creation, and environmental governance—interact, and overlap. From a Diverse Economies perspective, non-capitalist actors like social enterprises and family farms collaborate with capitalist enterprises such as cafés and coffee roasters, as well as publicly supported institutions like UTS. These exchanges address various needs, from improving soil quality to enhancing corporate Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) commitments, effectively “economising” the reverse logistics supply chain. These findings are consistent with others who have documented how community-based responses to organic waste rest upon more-than market and more-than Capitalist logics (e.g. Hobson and Lynch 2016; Morrow and Davies 2022; Zapata Campos et al 2023).

During the workshop and subsequent meetings, all participants agreed that the social enterprise representative’s assertion that they never collect waste without also collecting data, is a core principle of a reverse logistics supply chain. The value of this chain lies not only in soil improvement, plant growth, and carbon sequestration but also, consonant with the integrative and holistic approach of the SDGs, in realizing broader social, ecological, and economic impacts.

Thinking With the World, Minimising Harm

Reflecting on this in-vivo experiment to assemble a reverse supply chain for organic waste, we see how diverse organisations with different motivations can align for a greater good.

Since the initial workshop, researchers, farmers, café owners, and roasters have continued to meet to explore forming an alliance to advance this agenda. Initially, capacity will be small. Sydney produces 3,000 tons of SCG (spent coffee grounds) annually, a tiny fraction of its organic waste stream, which accounts for 50% of municipal waste (Planet Ark 2016). Mayor Clover Moore aims to divert 80% of this from landfills within seven years. As several participants in the workshop pointed out, because of its material properties–relatively lightweight, non-putrescible, not contaminated with weed seed–spent coffee grounds and chaff are good materials to learn from and with.

Redirecting organic waste from landfills to regenerative farms helps achieve sustainability targets while pursuing other beneficial goals. One critical need is soil improvement considering increasing acidification and the continuing decline of soil organic carbon (NSW EPA 2021). A farmer at our workshop, operating on a larger acreage, estimated requiring 6000 truckloads of soil-improving organics annually to achieve adequate ground cover. While growing high-value crops like garlic is one outcome, farmers like Michelle in the central west are also exploring industrial hemp. Hemp fibres can enhance cement’s durability, fire resistance, and aesthetic appeal when mixed, and hemp cultivation in the central west can sequester significant carbon—15 to 22 tons per hectare—while requiring minimal fertiliser with good soil (Adesina et al 2020). Like the reverse supply chain, regenerative hemp cultivation fosters diverse exchange relationships and links primary and secondary sectors with the building trades.

While there is considerable promise involved in scaling-out this relationship, the reverse circular supply chain’s “economisation” would require the construction and maintenance of relationships between growers, processors, and builders concurrent with the growth of the sector–a fact recognised as a recent industry conference.

Success in relation to both ventures in turn requires, we would argue, a different approach to risk and the possibilities of harm. George DeMartino (2022) argues against what he refers to as the moral geometry of harm which shapes much of the “tragic science” of economics. The risk of harm is at the centre of how mainstream economics conceptualises cost-benefit calculations. He represents this dominant conceptualisation of harm through the following syllogism.

- Harm is treated as inevitable, someone’s welfare will always be diminished,

- All harms of fungible, any harm can by compensated for

and - The economist role is there for the unbiased adjudication of cost, benefit, harm, and compensation

An alternative approach, for DeMartino, is to start with an approach that centres harm, particularly the perspectives of those most likely to be impacted by a process of change. He draws on recent efforts facilitated by the RAND corporation to convene a harm-centric approach to allocating water access in the Colorado River–a difficult situation now compounded by the consequences of climate change.

Taking a harm-centric approach, starting small, and nurturing relationships over time in an iterative, reflexive process, offers a way to minimise risks. The cautionary tale of Red Cycle underscores this approach. Initially a backyard social enterprise, Red Cycle rapidly became the main collectors of High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) waste for Australia’s supermarket giants, aiming to address single-use plastics concerns. However, the scheme collapsed when the market for this material proved insufficient, leaving municipalities in New South Wales and Victoria with warehouses of potentially hazardous material (Olamide et al 2024).

DeMartino suggests that leading with harm reframes how we view economics and economic futures. Rather than trying to predict the unpredictable future, he encourages us to ask, “What can we do today to shape the future to our liking?” (DeMartino, 2022, p. 203). Action research, like our own, embodies this approach by addressing future uncertainties and moving towards shared goals, included the SDGs. Building a reverse logistics supply chain using organic waste to regenerate soil represents a new regional vision where farms contribute significantly to mitigating climate change. In this context, while the future remains uncertain, our next steps are clear.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the ARC discovery scheme for supporting the innovative waste economies project (ARC Discovery Grant 20191.50389).

SDG Alignment

By centring social enterprises and diverse livelihoods this circular economy research shows the multiplier effect of thinking and dealing with waste differently and how this engages with multiple SDGs.

SDG 2 – Zero Hunger

Target 2.3

By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment

SDG 5 – Gender Equality

SDG 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities

SDG 12 – Responsible Consumption and Production

Target 12.2

By 2030, achieve the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources SDG 13 – Climate Action

Additional Resources

Healy, S., & Mellick Lopes, A. (2023). Postcapitalist composting: Reverse logistics and organic waste, designing for diverse livelihoods. Journal of Cultural Economy, 16(4), 622-630.

Communities Economies Institute. (2021, November 11). Drawing/Redrawing Economics: Waste and the appeal of circularity [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/7LxE3d0idPw?si=OruAQVmu4NMgZoZk

Mellick Lopes, A., Healy, S., & Zeibots, M. (2024, August). Commoning by design: Making room for life in the designed world. In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2024: Exploratory Papers and Workshops-Volume 2 (pp. 127-134).

Healy, S., & Mellick Lopes, A. (2024). Bringing organics back to the land: Co-creating the circular value chain. Circular Australia.

Healy, S., & Mellick Lopes, A. (2023). Postcapitalist composting: Reverse logistics and organic waste, designing for diverse livelihoods. Journal of Cultural Economy, 16(4), 622-630.

References

Adesina, I.; Bhowmik, A.; Sharma, H.; Shahbazi, A. A Review on the Current State of Knowledge of Growing Conditions, Agronomic Soil Health Practices and Utilities of Hemp in the United States. Agriculture 10 (2020): 129.

Çalışkan, Koray, and Michel Callon. “Economization, part 1: shifting attention from the economy towards processes of economization.” Economy and society 38, no. 3 (2009): 369-398.

Çalışkan, Koray, and Michel Callon. “Economization, part 2: a research programme for the study of markets.” Economy and society 39, no. 1 (2010): 1-32.

City of Sydney. (2017) Leave nothing to waste Sydney2030/Green/Global/Connected Managing resources in the City of Sydney area: Waste strategy and action plan 2017 – 2030. https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/-/media/corporate/files/2020-07-migrated/files_l/leave-nothing-to-waste-strategy-and-action-plan-20172030.pdf?download=true

DeMartino, George F. The tragic science: how economists cause harm (even as they aspire to do good). University of Chicago Press, 2022.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. “What is a Circular Economy?” https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/circular-economy-introduction/overview

Hawkins, Gay, and Stephen Healy. “Waste/economy/ecology: redrawing the circular economy.” Journal of Cultural Economy 16, no. 4 (2023): 576-578.

Healy, Stephen, and Abby Mellick Lopes. “Postcapitalist composting: reverse logistics and organic waste, designing for diverse livelihoods.” Journal of Cultural Economy 16, no. 4 (2023): 622-630.

Hobson, K. and Lynch, N. (2016). Diversifying and de-growing the circular economy: radical social transformation in a resource-scarce world. Futures 82, pp. 15-25. 10.1016/j.futures.2016.05.012 file

Hobson, Kersty, and Nicholas Lynch. “Diversifying and de-growing the circular economy: Radical social transformation in a resource-scarce world.” Futures 82 (2016): 15-25. 10.1016/j.futures.2016.05.012 file

Environmental Protection Authority. “NSW State of the Environment 2021.” Soe.epa.nsw.gov.au.

Morrow, O., and Anna Davies. “Creating careful circularities: community composting in New York City.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47, no. 2 (2022): 529-546.

Shittu, Olamide, Kate Arnautovic, Simon Lockrey, Joanna Vince, Roelof Vogel, Ananya Bhattacharya, Elyse Stanes, Nicole Garofano, Monique Retamal, and Matthew Harkness. “Governance Solutions for Soft Plastics in Australia: Lessons from the Discontinuation of REDcycle.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 31, no. 3 (July 2, 2024): 269–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2024.2367960.

Planet Ark and City of Sydney. “Coffee 4 Planet Ark.” https://planetark.org/newsroom/documents/coffee-4-planet-ark-trial-report

Quirk, Sam, Chris Gibson, and Nicole Cook. “More-than-transactional circular economies: the café-urban farm nexus and emergent regional food waste circuits.” Local Environment 29, no. 6 (2024): 750-765.

Zapata Campos, María José, Patrik Zapata, and Jessica Pérez Reynosa. “(Re) gaining the urban commons: everyday, collective, and identity resistance.” Urban Geography 44, no. 7 (2023): 1259-1284.

How to Cite this Chapter

Healy, Stephen, and Abby Mellick Lopes. (2025). “Redrawing the Circular Economy: Organic Waste and Peri-Urban Futures.” In Sustainable development without borders: Western Sydney University to the World . 2025 ed., edited by Emma Boddington, Bhadra Chandran, Jen Dollin, Jefrrey W. Har, Katies Hayes, Charina Kofod, Fiona Salisbury and Lucy Walton. Sydney: Western Sydney University, 2025. Available from https://doi.org/10.61588/TESB2263

Attribution

Redrawing the Circular Economy: Organic Waste and Peri-Urban Futures by A/Prof Stephen Healy and Prof Abby Mellick Lopes is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/