Version of Record (VoR)

Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G. O., Ishaya, T., Osuagwu, U. L., Abu, E. K., Nwaeze, O., Oloruntoba, R., … Agho, K. E. (2020). Factors associated with the myth about 5G network during COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal Of Global Health Reports, 4. https://doi.org/10.29392/001c.17606

Factors associated with the myth about 5G technology during COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa.

Running head: The myth about 5G technology during COVID-19 pandemic

Abstract

Background: Globally, the conspiracy theory claiming 5G technology can spread the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is making the rounds on social media and this could have significant effect in tackling the spread of the pandemic. This study investigated the impact of the myth that 5G technology is linked to COVID-19 pandemic among sub-Saharan Africans (SSA).

Methods: A cross sectional survey was administered on 2032 participants few weeks immediately after the lockdown in some SSA countries (April 18 – May 16, 2020). Participants were recruited via Facebook, WhatsApp, and authors’ technologys. The outcome measure was whether respondent believed that 5G technology was the cause of the coronavirus outbreak or not. Multiple logistic regression analyses using backward stepwise were used to examine the associated factors.

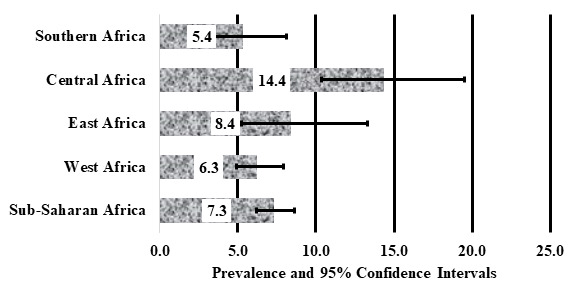

Findings: About 7.3% of the participants believed that 5G technology was behind COVID-19 pandemic. Participants from Central African reported the highest proportion (14.4%) while the lowest proportion (5.4%) was among those from Southern Africa. After adjusting for potential covariates in the multivariate analysis, Central Africans (Adjusted odds ratio, AOR 2.12; 95%CI: 1.20, 3.75), females (AOR 1.86; 95%CI: 1.20, 2.84) and those who were unemployed at the time of this study (AOR 1.91; 95%CI: 1.08, 3.36) were more likely to believe in the myth that 5G technology was linked to COVID-19 pandemic. After adjustment for all potential cofounders, participants who felt that COVID-19 pandemic will not continue in their country were 1.59 times (95%CI: 1.04, 2.45) more likely to associate the 5G technology with COVID-19 compared to those who thought that the disease will remain after the lockdown. Participants who were younger were more likely to believe in the 5G technology myth but the association between level of education and belief that 5G technology was associated with COVID-19 was nullified after adjustments.

Conclusions: This study found that 7.4% of adult participants held the belief that 5G technology was linked to COVID-19 pandemic. Public health intervention including health education strategies to address the myth that 5G was linked COVID-19 pandemic in SSA are needed and such intervention should target participants who do not believe that COVID-19 pandemic will continue in their country, females, those that are unemployed and those from Central African countries in order to minimize further spread of the disease in the region.

Keywords: COVID-19, Myths, sub-Saharan Africa, 5G technology, Attitude

Introduction

During the outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the subsequent global spread of the pandemic, there arose a myth that the outbreak was associated with the fifth generation mobile telecommunication technology, known as 5G [1]. Holding such myths could have implications for compliance with non-pharmaceutical preventive strategies prescribed for the control of the novel coronavirus [2]. These myths include that 5G was the cause of the novel coronavirus; that the electromagnetic radiation from the 5G technology was responsible for the mutation of the coronavirus; and that the 5G technology was a strategy of the industrialized nations to control the population of the less industrialized nations among others [2-4]. This is because of the fact that radiofrequency radiation (RF) is increasingly being identified as a new form of environmental pollution [3]

The fifth generation mobile telecommunication is the new, high-speed wireless communications technology, promising faster bandwidth speeds of 1 – 10 Gbps, wider coverage, reduced congestion and improved latency [4]. The technology is expected to be transformative, fueling innovation across every industry and every aspect of our lives. The combination of its high-speed and potential to transform the human way of life by fully supporting the implementation of Internet-of-things (IoT) solutions generated various myths about 5G.

Whereas myths are usually associated with individuals who may be unlearned in the subject matter, the myths of the harmful effects of 5G have been promoted by some scientists [1]. The evidence for the biological effects of mobile phone technology and non-ionizing radiofrequency used in the 5G technology are inconclusive at present [4-9]. While available research till date, do not reveal any adverse health effect being causally linked with exposure to wireless technologies, [10] further health related studies need to be carried out at the frequencies to be used by 5G. Notwithstanding the lack of evidence to support the link between the 5G technology and the pandemic, the myth has continued to grow globally. Besides the myth linking 5G technology with coronavirus, several other myths have been held regarding COVID-19 [11]

South Africa and Lesotho are the only countries in sub-Saharan Africa that have launched the 5G technology with limited coverage [12]. Notwithstanding, the myths about the association of the technology with the outbreak of COVID-19 continue to be held in sub-Saharan Africa. Myths (unsubstantiated beliefs) [13] [14] held by individuals have played a significant role in public health interventions including acceptance of immunization and use of preventive health strategies [15-18].

As the novel coronavirus outbreak assumed pandemic proportion, and as a result of lack of treatment and vaccine for the disease several community directed strategies are recommended to contain and mitigate the outbreak. Some of the recommended strategies include international and local travel restrictions, quarantine and self-isolation of suspected cases for a period equivalent to the incubation period of the disease (14 days), lockdown of commercial activities in major cities, closure of schools, restriction of movement, frequent hand washing, use of face masks and social distancing [19]. It is widely believed that the spread of the virus in the community can be minimized if citizens follow these recommendations and practices.

There have been concerns with the level of compliance with these preventive strategies in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. Using the health belief model (HBM) it has been postulated that behavior and perception influence the development of preventive health behavior [20]. This study was designed to examine factors associated with the myth that 5G technology was linked to COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from this research will enable researchers and policy makers target sub-population who will not comply with preventive measures proposed for the mitigation of the present pandemic and any other outbreaks when myths held by these sub-populations are the reasons for non-compliance.

Methodology

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted between April 18 and May 16, 2020 when most of the countries surveyed were under mandatory lockdown and restriction of movement. As it was not feasible to perform nationwide community-based sample survey during this period, the data were obtained electronically via survey monkey. Only participants who had access to the internet, were on the respective social media platforms and used them, may have participated. An e-link of the structured synchronized questionnaire was posted on social media platforms (Facebook and WhatsApp) which were commonly used by the locals in the participating countries, and was sent via emails by the researchers to facilitate response. The questionnaire included a brief overview of the context, purpose, procedures, nature of participation, privacy and confidentiality statements and notes to be filled out.

Study population

The participants were sub-Saharan African nationals from different African countries either living abroad or in their countries of origin including Ghana, Cameroun (only distributed to the English speaking regions), Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda etc. To be eligible for participation, participants had to be 18 years and over, and should be able to provide online consent.

Survey questionnaire

The survey tool for the COVID-19 knowledge questionnaire was developed based on the guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO) for clinical and community management of COVID-19. The questionnaire was adapted with some modifications to suit this study’s objective namely to explore the potential impact of the myth about the 5G technology on compliance with strategies to control the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Prior to launching of the survey, a pilot study was conducted to ensure clarity and understanding as well as to determine the duration for completing the questionnaire. Participants (n=10) who took part in the pilot were not part of the research team and did not participate in the final survey as well. This self-administered online questionnaire consisted of 58 items divided into four sections (demographic characteristics, knowledge, attitude, perception and practice). Supplementary Table 1 is a sample of the tables showing the items used in the data analysis.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable for this study was Myth about the 5G technology which was categorized as “Yes” (1 = if COVID-19 is associated with 5G communication) or “No” (0 = if COVID-19 is not associated with 5G communication).

Independent variables

The independent variables included: a) demographic characteristics of the participants which included age, country of origin, country of residence, sex, religion, educational, marital and occupational status; b) attitude towards COVID-19 which included practice of self-isolation, home quarantine, number of people living together in the household; c) compliance during COVID-19 lockdown which included whether they attended a crowded event, used face mask when going out, practiced regular hand-washing, used hand sanitizers; and d) risk perception which included whether participants think they were at risk of becoming infected, at risk of dying from the infection, if they were worried about contracting COVID-19, and thought the infection will continue in their country (Table 1).

Table 1. Covariates used in the multiple logistic regression

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region*and Socio-demographic

Age in years Sex Marital Status Highest level of Education Employment status Religion Occupation Number living together |

Region*and Socio-demographicᵖ

Attitude towards Covid-19 Self-Isolation Home quarantined due to Covid-19 |

Region*and Socio-demographic and attitudeᵖ

Compliance during lockdown during Covid -19 Attended crowded religious events Wore mask when going out Practiced regular Hand washing |

Region*and Socio-demographic and attitude and Complianceᵖ

Covid-19 risk perception$ Risk of becoming infected Risk of becoming severely infected Risk of dying from the infection How much worried are you about COVID-19 How likely do you think Covid-19 will continue in your country Concern for self and family if COVID-19 continues |

| * West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa & Southern Africa; $ High/ very worried/very concerned/very likely for “High/ Concerned/worried & Very High/ Extremely Concerned/extremely worried” & Low/ not worried/ not concerned/no very likely for" Very low/Not at all/ Very unlikely/ Extremely unconcerned; Unlikely/Unconcerned/ A little & Neither likely nor unlikely/moderate/ Neither Concerned nor Unconcerned ᵖ = only significant variables were added. |

|||

Data analysis

Demographic, compliance during lockdown, attitude and perception variables were summarized as counts and percentages for categorical variables. and two-way frequency table was used to obtain the proportion estimates of those who reported that 5G technology was linked to COVID-19. In the univariate and bivariate analyses, Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated in order to assess the unadjusted risk of independent variables on selected covariates.

In the univariate logistic regression analysis, variables with a p-value <0.20 were retained and used to build a multivariable logistic regression model which examined the factors associated with the myth about 5G technology during COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, we performed a stage modelling technique employed by Dibley et al. [24], and a four-staged modelling technique was employed. In the first stage, regions and demographic factors were entered into a baseline multivariable model. We then conducted a manually executed elimination method to determine factors associated with the myth about 5G technology during COVID-19 pandemic at P <0.05. The significant factors in the first stage were added to attitude towards COVID-19 variables in the second staged model; this was then followed by manually executed elimination procedure and variables that were associated with the study outcomes at P <0.05 were retained in the model. We used a similar approach for compliance to public health measures and COVID-19 risk perception factors in the third and fourth stages, respectively. The odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were also calculated to assess the adjusted factors. All analyses were performed in Stata version 14.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval for the study was sought and obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Cross River State Ministry of Health (CRSMOH/HRP/HREC/2020/117). The study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration for Human Research. The confidentiality of participants was assured in that no identifying information was obtained from participants. The study adhered to the tenets of Helsinki’s declaration and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to completing the survey. Participants were required to answer a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the consent question during survey completion to indicate their willingness to participate in this study.

Results

Demography of participants

Table 2 shows the descriptive data of the participants. Of the 1969 participants that indicated their country of residence, majority (n=1,108, 56.3%) were from West Africa and few from East Africa (n = 209, 10.6%). Over 65% of the participants were aged 38 years or younger and 55.2% were males. More than two-third of the participants (79.2%) had at least a Bachelor degree while 20.8% had either a secondary or primary (basic) school education. About 52% were living with 4 – 6 persons during the study period while 18.6% lived alone.

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Demography | |

| Region | |

| West Africa | 1,108 (56.3) |

| East Africa | 209 (10.6) |

| Central Africa | 251 (12.7) |

| Southern Africa | 401 (20.4) |

| Place of residence | |

| Locally (Africa) | 1855(92.5) |

| Diaspora | 150 (7.5) |

| Age category | |

| 18-28 years | 775 (39.0) |

| 29-38 years | 530 (26.7) |

| 39-48 years | 441 (22.2) |

| 49+years | 242 (12.1) |

| Sex | |

| Males | 1099 (55.2) |

| Females | 892 (44.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 879(44.1) |

| Not married | 1116 (55.9) |

| Highest level of Education | |

| Postgraduate Degree (Masters /PhD) | 642 (32.2) |

| Bachelor’s degree | (939) 47.0 |

| Secondary/Primary | 416 (20.8) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 1321 (66.0) |

| Unemployed | 679 (34.0) |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | 1763 (88.4) |

| Others | 232 (11.6) |

| Occupation | |

| Non-health care sector | 1,471 (77.3) |

| Health care sector | 433 (22.7) |

| Number living together | |

| <3 people | 506(28.8) |

| 4-6 people | 908 (51.7) |

| 6+ people | 341 (19.4) |

| Attitude towards Covid-19 | |

| Self-Isolation | |

| No | 1237 (66.7) |

| Yes | 564 (31.3) |

| Home quarantined due to Covid-19 | |

| No | 1091 (60.7) |

| Yes | 707 (39.3) |

| Do you live alone during COVID-19 | |

| No | 1,624 (81.4) |

| Yes | 372 (18.6) |

| Compliance during Covid-19 lockdown | |

| Attended crowded religious events | |

| No | 1097 (54.0) |

| Yes | 935 (46.0) |

| Wore mask when going out | |

| No | 485 (23.9) |

| Yes | 1547 (76.1) |

| Practiced regular Handwashing | |

| No | 762 (37.5) |

| Yes | 1270 (62.5) |

| Covid-19 Risk Perception | |

| Risk of becoming infected | |

| High | 669 (37.2) |

| Low | 1128 (62.8) |

| Risk of becoming severely infected | |

| High | 466 (25.9) |

| Low | 1333 (74.1) |

| Risk of dying from the infection | |

| High | 349 (19.5) |

| Low | 1445 (80.6) |

| How worried are you because of COVID-19 | |

| worried | 1037 (57.5) |

| not worried | 766 (42.5) |

| How likely do you think COVID-19 will continue in your country | |

| Very likely | 1152 (64.0) |

| not very likely | 649 (36.0) |

| Concern for self and family if COVID-19 continues | |

| Concerned | 1667 (94.2) |

| Not concerned | 102 (5.8) |

| Outcome measure | |

| COVID caused by 5G | |

| No | 1723 (92.6) |

| Yes | 137 (7.4) |

Perspective of Sub-Saharan Africans on 5G technology and COVID-19

The belief that 5G technology was linked to the COVID-19 pandemic was upheld by 7.4% of the participants in this study, and some participants (31.3%) stated that they practiced self-isolation while 39.3% practiced home quarantine during the pandemic. Responding to the question of how worried they were about COVID-19, over 57% of the participants stated that they were either very worried or somehow worried about the disease (Table 2). During the COVID-19 lockdown in SSA, nearly half (46%) of the participants in the study attended crowded religious events and a majority (76.1%) wore a mask when going out.

Figure 1 showed the regional proportion and 95% confidence intervals of participants in this study who believed 5G technology was behind COVID-19 pandemic in Sub-Saharan Africa. According to the figure, Central Africa had the highest proportion (14.4%) of participants that believe in the 5G technology myth while few participants (5.4%) from Southern Africa believed in the 5G technology myth.

Table 3 reported the proportion and unadjusted odds ratio (OR) as well as the 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio that 5G technology was associated with COVID-19. The unadjusted odd ratios revealed that participants from Central African countries, female participants, those who were not married and unemployed, and participants with primary/secondary education qualification, were more likely to believe that 5G technology was linked to the COVID-19 disease. Compared with the younger age group (age 18-28 years), older participants (29 to 48 years) were less likely to believe that 5G technology was linked to the COVID-19 pandemic while, those who perceived that COVID-19 was less likely to continue in their country were 1.50 times (95% confidence interval of unadjusted odds ratio 1.05 – 2.15) more likely to believe that 5G technology was linked to COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 3).

| Variables | Proportion | Odds Ratio | [95%CI] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | ||||

| Country of origin | ||||

| West Africa | 6.3 | 1.00 | ||

| East Africa | 8.4 | 1.38 | [0.78, 2.44] | 0.271 |

| Central Africa | 14.4 | 2.51 | [1.61, 3.93] | <0.001 |

| Southern Africa | 5.4 | 0.85 | [0.51, 1.42] | 0.531 |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Local | 7.4 | 1.00 | ||

| Diaspora | 8.3 | 1.15 | [0.60, 2.00] | 0.678 |

| Age category | ||||

| 18-28 years | 10.7 | 1.00 | ||

| 29-38 years | 5.6 | 0.5 | [0.32, 0.79] | <0.001 |

| 39-48 years | 3.7 | 0.32 | [0.18, 0.57] | <0.001 |

| 49+years | 7.8 | 0.70 | [0.41, 1.21] | 0.202 |

| Sex | ||||

| Males | 5.5 | 1.00 | ||

| Females | 9.5 | 1.80 | [1.26, 2.57] | <0.001 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 5.7 | 1.00 | ||

| Not married | 8.7 | 1.56 | [1.08, 2.25] | 0.017 |

| Highest level of Education | ||||

| Postgraduate Degree | 5.4 | 1.00 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 8.1 | 1.53 | [1.00, 2.35] | 0.051 |

| Secondary/Primary | 8.8 | 1.69 | [1.02, 2.80] | 0.041 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 5.6 | 1.00 | ||

| Unemployed | 10.9 | 2.08 | [1.46, 2.96] | <0.001 |

| Religion | ||||

| Christianity | 7.5 | 1.00 | ||

| Others | 6.1 | 0.80 | [0.45, 1.45] | 0.47 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Non-health care sector | 7.6 | 1.00 | ||

| Health care sector | 7.4 | 0.96 | [0.63, 1.47] | 0.856 |

| Number living together | ||||

| <3 people | 6.3 | |||

| 4-6 people | 8.6 | 1.41 | [0.90, 2.21] | 0.133 |

| 6+ people | 7.8 | 1.27 | [0.73, 2.20] | 0.406 |

| Attitude | ||||

| Self-Isolation | ||||

| No | 6.7 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 8.4 | 1.29 | [0.89, 1.87] | 0.186 |

| Home quarantined due to Covid-19 | ||||

| No | 6.3 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 8.7 | 1.43 | [0.99, 2.05] | 0.054 |

| Compliance with mitigation practices | ||||

| Attended crowded religious events | ||||

| No | 6.5 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 8.6 | 1.37 | [0.96, 1.93] | 0.08 |

| Wore mask when going out | ||||

| No | 7.3 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 7.4 | 1.01 | [0.68, 1.50] | 0.978 |

| Practiced regular Hand washing | ||||

| No | 9 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 6.6 | 0.71 | [0.50, 1.01] | 0.06 |

| Risk Perception | ||||

| Risk of becoming infected | ||||

| High | 8.5 | 1.00 | ||

| Low | 6.5 | 0.74 | [0.52, 1.07] | 0.106 |

| Risk of becoming severely infected | ||||

| High | 9 | 1.00 | ||

| Low | 6.6 | 0.71 | [0.49, 1.05] | 0.085 |

| Risk of dying from the infection | ||||

| High | 8 | 1.00 | ||

| Low | 7.1 | 0.87 | [0.56, 1.35] | 0.533 |

| Worried are you because of COVID-19 | ||||

| Very worried | 7 | |||

| not very worried | 7.4 | 1.05 | [0.73, 1.50] | 0.805 |

| Concern for self and family if COVID-19 continues | ||||

| Very concerned | 7 | |||

| Not very concerned | 10.8 | 1.6 | [0.83, 3.08] | 0.158 |

| Likelihood of COVID-19 continuing in your country | ||||

| Very likely | 6.3 | 1.00 | ||

| not very likely | 9.1 | 1.50 | [1.05, 2.15] | 0.027 |

| Variables with confidence intervals CI that include ‘1’ were not statistically significant in the model. | ||||

Table 4 showed the independent predictors of the association between 5G technology and COVID-19 disease. Participants who were living in Central Africa, females, and those who were unemployed at the time of this study were more likely to associate 5G technology with COVID-19. Also, belief in the 5G technology myth was associated with participants’ level of risk perception, such that those who felt that the disease was not going to continue in their various countries after the lockdown were more likely to associate 5G technology with COVID-19 disease (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.57, 95%CI 1.07 – 2.31) compared with those who felt that the disease was more likely to remain in their respective countries after the lockdown. Participants with low risk perception of contracting the infection, and those who were aged 39-48 years were less likely to associate 5G technology with COVID-19 compared to those who had high risk perception of contracting the infection and younger participants, respectively.

| Variables | Predictors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | Odds Ratio | [95%CI] | P value |

| Country of origin | |||

| West Africa | 1.00 | ||

| East Africa | 1.30 | [0.70, 2.41] | 0.406 |

| Central Africa | 2.03 | [1.25, 3.30] | 0.004 |

| Southern Africa | 0.79 | [0.46, 1.35] | 0.39 |

| Age category | |||

| 18-28years | 1.00 | ||

| 29-38 | 0.59 | [0.34, 1.05] | 0.073 |

| 39-48 | 0.45 | [0.22, 0.94] | 0.035 |

| 49+years | 1.07 | [0.55, 2.10] | 0.835 |

| Sex | |||

| Males | 1.00 | ||

| Females | 1.59 | [1.09, 2.34] | 0.017 |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 1.00 | ||

| Unemployed | 1.64 | [1.00, 2.70] | 0.049 |

| Risk perception | |||

| Risk of becoming infected | |||

| High | 1.00 | ||

| Low | 0.64 | [0.43, 0.94] | 0.023 |

| How likely do you think COVID-19 will continue in your country? | |||

| Very likely | |||

| not very likely | 1.57 | [1.07, 2.31] | 0.022 |

| ORs=adjusted odds ratios; CI: Confidence intervals Variables with confidence intervals CI that include ‘1’ were not statistically significant in the model. Backward stepwise regression model was conducted. |

|||

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study from SSA to examine key factors associated with the myth about 5G technology and COVID-19 as well as how this myth influences compliance with prescribed behavioral measures to control the spread of the disease. The study found that, irrespective of whether participants were living within the sub-region or in the diaspora, nearly one in every thirteen adult participants from SSA believed that 5G technology was linked with the outbreak of COVID-19. This was more among those from Central African and East African countries, where the proportions were 14% and 8%, respectively. After adjusting for all potential cofounders, participants from Central Africa, females, those that were unemployed and individuals in this study who thought that COVID-19 was not going to continue in their country after the lockdown, were more likely to hold this myth. There was a consistent strong association between older age (39-48yrs) and the lower likelihood of believing in the 5G myth. Perception of risk of contracting the infection was associated with the belief in the 5G myth.

The findings of this study were in concordance with a study conducted in England which reported that about 10 – 15% of the participants showed constant and very high levels of endorsements of the myth and those who believed that 5G technology was linked with the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with less compliance with government preventive measures [2]. In a new study conducted in Australia [21], researchers found that men and people aged 18-25 were more likely to believe COVID-19 myths and this was more among people from a non-English speaking background. We found similar associations with young people indicating that significant proportion of younger people (18-28 years) reported that 5G technology was associated with COVID-19 pandemic while those aged between 39 and 48 years were less likely to believe in the 5G technology myth after adjusting for all potential cofounders. This preponderance of young people may be due to the fact that younger people (aged 18 – 29 years) in SSA are more likely to own smartphones compared to older ones aged 50 and older [22]. There is need to reach young people with health messages particularly, since they are less likely to have symptoms, and as such may not meet testing criteria such as having a sore throat, fever or cough; more likely to have more social contacts through seeing friends more often, which increases their potential for spreading COVID-19, and can potentially be hospitalized with COVID-19 with severe complications in some despite their age.

The study conducted in England observed that endorsement of the coronavirus conspiracy belief was associated with less compliance to government preventive measures [2]. Although the proportion of participants who held the 5G myth was less than those who held similar belief in the England study [2], it should not be treated lightly especially for the fact that currently there is no end in sight for a medication or vaccine for COVID-19 and the fear of a second wave is staggering. Such myths or conspiracy beliefs in the midst of a pandemic crisis can have far-reaching consequences for the introduction of a vaccine in this region, with belief in anti-vaccine myths being linked to potential non-compliance [23,24].

Although the present study could not corroborate these fears as participants, who held the myth that 5G was linked to the coronavirus pandemic had similar rate of compliance with the precautionary measures put in place to minimize the spread of the infection compared with those who did not hold the belief. A study conducted in England observed that endorsement of the coronavirus conspiracy belief was associated with non-compliance with government preventive measures [2], with another worrying phenomenon being that, myths are never benign and people who hold one myth are more likely to believe other unrelated ones [2,25]. In this study, participants who thought the infection will not continue after the lockdown were more likely to associate it with the 5G myth. Our suggestion therefore is that there must be concerted regional and global educational campaigns to recondition the minds of the populace before the introduction of a vaccine. Freeman et al. (2020) did not only observe a significant association between the myths and non-compliance with preventive guidelines but also the participants’ skepticism to undertake future tests and vaccinations.

The differing levels of belief in the 5G myth among participants across the SSA sub-region as well as between other studies may reflect varying degrees of drivers of the myths such as mistrust [26] and other related consequences. Social identity including religion and nationality are known to promote the belief of myths [27]. Surveys in the USA and the United Kingdom found strong association between holding the myth and national narcissism (the trust in the greatness of one’s country) such that people who scored high in national narcissism were more likely to believe and disseminate myths about COVID-19 [28]. Unlike a previous study [2], the current study did not find any significant association between the 5G myth and the different religious groups. This is probably due to the disproportionate over-representation of Christians over other religious groups in this study.

Factors such as lower income and education levels [29], low social standing [30] and less ability to analyze [31] have all been linked to holding to myths. It was therefore not surprising that in the present study, with everything held equal, participants who have a bachelor’s degree or less and those who were unemployed were more likely to believe that the 5G technology was associated with the outbreak of coronavirus infection. Further ramifications are that the worsening economic conditions resulting from the coronavirus counter-measures can trigger or aggravate contiguous myths relating to the pandemic and further derail future efforts towards the introduction of medical interventions through tests and vaccinations. It is important that researchers interpret the finding that education is linked to the myth of 5G technology with caution, particularly as the participants in this study are biased regarding education.

The finding that that after controlling for all potential cofounders, participants who did not think that the infection will continue after the lockdown despite the lack of vaccine were more likely to associate the infection with the 5G technology validates the propositions of the health belief model (HBM). Constructs of HBM, specifically perceived susceptibility and perceived severity postulate that individuals will take actions to prevent or reduce a health problem if they perceive themselves as susceptible to the health problem or if they perceive the health problem will have serious consequences [20]. Perhaps the perception that the pandemic was being engineered by a telecommunication technology also led to their belief that they were less susceptible to the disease or that it would have trivial or minor health consequence.

Since many of the SSA countries still do not have the 5G technology, it is unlikely to accurately predict the impact of such belief on their attitude towards the 5G technology, however, early educational campaigns prior to the launch of the technology is recommended. Ensuring that people understand the benefits of the technology and how this can improve connectivity of people and access to information will facilitate the introduction and dissuade such belief. In addition, further studies targeting the SSA populations most affected by this belief are therefore recommended.

In considering the results from this study and the implications, the following limitations in the study should be noted. Given the difficulty of obtaining random sample from the study population, a convenient sampling technique was employed and this may affect the generalizability of the study results. However, during the lockdown, this was the only feasible way of collecting data from participants and this study provides an insight on the subject matter in the population surveyed. The data may be skewed towards those who may have access to internet and regularly use the social media platforms used in distributing the survey questionnaire. Being an electronic survey, residents in SSA who do not have access to the internet may have been unduly excluded from the study, which may account for the preponderance of the younger age group (over 65% were 38 years or younger). Furthermore, deploying the questionnaire in English language also excluded the non-English speaking residents in SSA such as the French-speaking people from the Central and West African region. When interpreting the present results, researchers should be cautious especially as non-response is not known most probably because, we do not know who has received an invitation to participate. In addition, as this was a cross-sectional study and findings may be due chance, the estimates reported may have overestimated or underestimated 5G myths linked to COVID-19 in SSA and causality cannot be assumed.

Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrated that 7.4% of adult participants in this study associated 5G technology with the outbreak of COVID-19, more in young people, females, those living in Central Africa and participants who were unemployed at the time of this study. Public health intervention including health education strategies to address the myth that 5G was linked COVID-19 pandemic in SSA are needed and such intervention should target these participants including those who do not believe that COVID-19 pandemic will continue in their country, in order to minimize further spread of the disease in the region.

Conflicts of interest Authors declare no conflict of interest

Ethics approval This study was approved by the Health Research and Ethics Committee, of the institution and was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration for Human Research. The confidentiality of participants was assured in that no identifying information was obtained from participants.

Consent to participate Informed consent was obtained online from all participants prior to completing the survey

Consent for publication Not applicable

Availability of data and material All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work

References

-

Ahmed W, Vidal-Alaball J, Downing J, López Seguí F. COVID-19 and the 5G Conspiracy Theory: Social Technology Analysis of Twitter Data. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19458.

-

Freeman D, Waite F, Rosebrock L, Petit A, Causier C, East A, et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychological Medicine. 2020:1-13 doi:10.1017/s0033291720001890 [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central] [PubMed]

-

Russell CL. 5G wireless telecommunications expansion: Public health and environmental implications. Environ Res. 2018;165:484-95. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2018.01.016 [Google Scholar]

-

Simko M., Mattsson M-O. 5G Wireless Communication and Health Effects—A Pragmatic Review Based on Available Studies Regarding 6 to 100 GHz. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3406 – 29. doi:10.3390/ijerph16183406 [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central] [PubMed]

-

Johansen C. Electromagnetic fields and health effects-epidemiologic studies of cancer, diseases of the central nervous system and arrhythmia-related heart disease. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2004;30:1 – 80. [Google Scholar]

-

Di Ciaula A. Towards 5G communication systems: Are there health implications? International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2018;221:367-75. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.01.011 [Google Scholar]

-

Belpomme D, Hardell L, Belyaev I, Burgio E, Carpenter DO. Thermal and non-thermal health effects of low intensity non-ionizing radiation: An international perspective. Environmental Pollution. 2018;242:643-58. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.07.019 [Google Scholar]

-

Kostoff RN, Heroux P, Aschner M, Tsatsakis A. Adverse health effects of 5G mobile technologying technology under real-life conditions. Toxicology Letters. 2020;323:35-40. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2020.01.020 [Google Scholar]

-

Vanderstraeten J, Verschaeve L. Biological effects of radiofrequency fields: Testing a paradigm shift in dosimetry. Environmental Research. 2020;184:109387. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109387 [Google Scholar]

-

WHO. 5G technologys and health. 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/5g-mobile-technologys-and-health. Accessed May 14, 2020.

-

Organization WH. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: myth busters. 2020. Available: www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters? Accessed June 14, 2020.

-

Harsine K. Is Africa ready for 5G? 2019. Available: https://www.dw.com/en/is-africa-ready-for-5g. Accessed June 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

-

Casazza K, Fontaine KR, Astrup A, Birch LL, Brown AW, Bohan Brown MM, et al. Myths, presumptions, and facts about obesity. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:446-54. doi:10.1056/nejmsa1208051 [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central] [PubMed]

-

Viehbeck SM, Petticrew M, Cummins S. Old myths, new myths: challenging myths in public health. American journal of public health. 2015;105:665-9. doi:10.2105/ajph.2014.302433 [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central] [PubMed]

-

Fiaveh D Y. Condom Myths and Misconceptions: The Male Perspective. Global J Med Res. 2012;12:43 – 50. [Google Scholar]

-

Cohen S A. Abortion and Mental Health: Myths and Realities. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2006;9:8 – 16. [Google Scholar]

-

Clift K, Rizzolo D. Vaccine myths and misconceptions. Journal of the American Academy of PAs. 2014;27. doi:10.1097/01.jaa.0000451873.94189.56 [Google Scholar]

-

Davidson M. Vaccination as a cause of autism-myths and controversies. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2017;19:403-7. doi:10.31887/dcns.2017.19.4/mdavidson [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central] [PubMed]

-

Control CfD. Implementation of Mitigation Strategies for Communities with Local COVID-19 Transmission. In: Control CfD, editor.: Centers for Disease Control; 2020. p. 1 – 10. [Google Scholar]

-

Jones CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL, Brown NR, Christy K, Weaver J. The Health Belief Model as an explanatory framework in communication research: exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Commun. 2015;30:566-76. doi:10.1080/10410236.2013.873363 [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central] [PubMed]

-

Pickles K, Cvejic E, Nickel B, Copp T, Bonner C, Leask J, et al. COVID-19: Beliefs in misinformation in the Australian community. medRxiv. 2020:2020.08.04.20168583. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089177 [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central] [PubMed]

-

Silver L, S C. Internet Connectivity Seen as Having Positive Impact on Life in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington D C: Pew-Research Center; 2018. doi:10.1101/2020.08.04.20168583 [Google Scholar]

-

Jolley D, Douglas KM. Prevention is better than cure: Addressing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2017;47:459-69. [Google Scholar]

-

Jolley D, Douglas KM. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89177. doi:10.1111/jasp.12453 [Google Scholar]

-

Swami V, Chamorro-Premuzic T, Furnham A. Unanswered questions: A preliminary investigation of personality and individual difference predictors of 9/11 conspiracist beliefs. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2010;24:749-61. doi:10.1002/acp.1583 [Google Scholar]

-

Goreis A, Voracek M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Psychological Research on Conspiracy Beliefs: Field Characteristics, Measurement Instruments, and Associations With Personality Traits. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:205. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00205 [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central] [PubMed]

-

Douglas KM, Uscinski JE, Sutton RM, Cichocka A, Nefes T, Ang CS, et al. Understanding Conspiracy Theories. Political Psychology. 2019;40:3-35. doi:10.1111/pops.12568 [Google Scholar]

-

Sternisko A, Cichocka A, Cislak A, Van Bavel JJ. Collective narcissism predicts the belief and dissemination of conspiracy theories during COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. doi:10.31234/osf.io/4c6av [Google Scholar]

-

Douglas KM, Sutton RM, Callan MJ, Dawtry RJ, Harvey AJ. Someone is pulling the strings: hypersensitive agency detection and belief in conspiracy theories. Thinking & Reasoning. 2016;22:57-77. doi:10.1080/13546783.2015.1051586 [Google Scholar]

-

Freeman D, Bentall RP. The concomitants of conspiracy concerns. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:595-604. doi:10.1007/s00127-017-1354-4 [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central] [PubMed]

-

Swami V, Voracek M, Stieger S, Tran US, Furnham A. Analytic thinking reduces belief in conspiracy theories. Cognition. 2014;133:572-85. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2014.08.006 [Google Scholar]

Supplementary Table: Sample of survey tool used in the study

CONSENT

- I willingly agree to participate in this survey because I am interested in contributing to the knowledge and perceptions on Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemia. I understand that there are no forms of payments or reward associated with my participation.

- UNDERSTOOD, AGREE AND INTERESTED

- NOT UNDERSTOOD, DISAGREE AND NOT-INTERESTED

- Country of origin

- Country of residence

- Province/State/County

- Gender

- MALE

- FEMALE

- OTHERS

- Age (Years)

- Marital Status

- SINGLE

- MARRIED

- SEPARATED/DIVORCED

- WIDOW/WIDOWER

- Religion

- MUSLIM

- CHRISTIAN

- AFRICAN TRADITIONALIST

- OTHERS

- Highest level of education

- PRIMARY SCHOOL

- HIGH/SECONDARY SCHOOL

- POLYTHECNIC/DIPLOMA

- UNIVERSITY DEGREE (Bachelors/Professional)

- POSTGRADUATE DEGREE (Masters/PhD)

- Employment Status

- SELF EMPLOYED

- EMPLOYED

- UNEMPLOYED

- STUDENT/NON-STUDENT

- Occupation

- Do you live alone?

- YES

- NO

- If you live with family/friends, how many of you live together?

General KNOWLEDGE of COVID-19 Origin and outbreak

- Are you aware of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak?

- YES

- NO

- Are you aware of the origin of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak?

- YES

- NO

- Do you think Coronavirus disease (C0VID-19) outbreak is dangerous?

- YES

- NO

- Do you think Public Health Authorities in your country are doing enough to control the Coronavirus disease (C0VID-19) outbreak?

- YES

- NO

- Do you think Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has little effect(s) on Blacks than on Whites?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

KNOWLEDGE OF PREVENTION

- Do you think Hand Hygiene / Hand cleaning is important in the control of the spread of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- Do you think ordinary residents can wear general medical masks to prevent the infection by the COVID-19 virus?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- Do you think Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is associated with 5G communication?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- Do you think antibiotics can be effective in preventing Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- If yes to Q22 above, have you purchased an antibiotic in response to COVID-19 disease outbreak?

- YES

- NO

- Do you think there are any specific medicines to treat Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- Do you think there would be a vaccine for preventing Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in the next 6 months?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- Do you think Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was designed to reduce world population?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

KNOWLEDGE OF SYMPTOMS

- The main clinical symptoms of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) are: (Type “YES” or “NO” to the suggested options as applicable)

- FEVER

- FATIGUE

- DRY COUGH

- SORE THROAT

- Unlike the common cold, stuffy nose, runny nose, and sneezing are less common in persons infected with the COVID-19 virus.

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- There currently is no effective cure for COVID-2019, but early symptomatic and supportive treatment can help most patients recover from the infection

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- It is not necessary for children and young adults to take measures to prevent the infection by the COVID-19 virus.

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- COVID-19 individuals cannot spread the virus to anyone if there’s no fever.

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- The COVID-19 virus spreads via respiratory droplets of infected individuals

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

KNOWLEDGE OF PREVENTION

- To prevent getting infected by Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), individuals should avoid going to crowded places such as train stations, religious gatherings, and avoid taking public transportation

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- Isolation and treatment of people who are infected with the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) virus are effective ways to reduce the spread of the virus. The observation period is usually 14 days

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- Not all persons with COVID-2019 will develop to severe cases. Only those who are elderly, have chronic illnesses, and are obese are more likely to be severe cases.

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- Have you or anyone you know been affected by the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in any way(s)?

- YES

- NO

- If Yes to Q36 above, how did the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) affect you or that person you know? (Type “YES” or “NO” as applicable to the listed effects)

- LOST JOB

- LOST/CLOSED DOWN BUSINESS

- CONTRACTED COVID-19

- HOSPITALIZED DUE TO COVID-19

- COMPLETELY SEPARATED FROM FAMILY

- COMPLETELY STRANDED IN A FOREIGN COUNTRY/AWAY FROM REGULAR HOME/IN A DIFFERENT LOCATION FROM USUAL LOCATION OF RESIDENT

PERCEPTION OF RISK OF INFECTION

- Risk of becoming infected.

- VERY HIGH

- HIGH

- LOW

- VERY LOW

- UNLIKELY

- Risk of becoming severely infected

- VERY HIGH

- HIGH

- LOW

- VERY LOW

- UNLIKELY

- Risk of dying from the infection

- VERY HIGH

- HIGH

- LOW

- VERY LOW

- UNLIKELY

- How worried are you because of COVID-19?

- A GREAT DEAL

- A LOT

- A MODERATE AMOUNT

- A LITTLE

- NONE AT ALL

- How do you feel about the self-isolation? (Type “YES” or “NO” to the suggested options as applicable)

- WORRIED

- BORED

- FRUSTRATED

- ANGRY

- ANXIOUS

- I consider the self-isolation as necessary and reasonable

- STRONGLY AGREE

- AGREE

- NEITHER AGREE, NOR DISAGREE

- DISAGREE

- STRONGLY DISAGREE

- Do you think that if you are able to hold your breath for 10 seconds, it’s a sign that you don’t have COVID-19?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- If you drink hot water, it flushes down the virus

- STRONGLY AGREE

- AGREE

- NEITHER AGREE, NOR DISAGREE

- DISAGREE

- STRONGLY DISAGREE

WE HAVE TWO OUTCOMES VARIABLES FOR CHLOROQUINE STUDY

- Perception and Action

- Do you believe that Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) can be cured by taking Chloroquine tablets?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- If yes to Q46 above, have you purchased Chloroquine for the Coronavirus (COVID-19)?

- YES

- NO

- How likely do you think Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) will continue in your country?

- VERY LIKELY

- LIKELY

- NEITHER LIKELY, NOR UNLIKELY

- UNLIKELY

- VERY UNLIKELY

- If Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues in your country, how concerned would you be that you or your family would be directly affected?

- EXTREMELY CONCERNED

- CONCERNED

- NEITHER CONCERNED, NOR UNCONCERNED

- UNCONCERNED

- EXTREMELY UNCONCERNED

PRACTICE REGARDIING COVID-19

- In recent days, have you gone to any crowded place including religious events?

- ALWAYS

- SOMETIMES

- RARELY

- NOT AT ALL

- NOT SURE

- In recent days, have you worn a mask when leaving home?

- ALWAYS

- SOMETIMES

- RARELY

- NOT AT ALL

- NOT SURE

- In recent days, have you been washing your hands with soap and running water for at least 20 seconds each time?

- ALWAYS

- SOMETIMES

- RARELY

- NOT AT ALL

- NOT SURE

- Are you currently or have you been in (domestic/home) quarantine because of COVID-19?

- YES

- NO

- Are you currently or have you been in self-isolation because of COVID-19?

- YES

- NO

- Since the government gave the directives on preventing getting infected, have you procured your mask and possibly sanitizer?

- YES

- NO

- Have you travelled outside your home in recent days using the public transport

- YES

- NO

- Are you encouraging others that you come in contact with to observe the basic prevention strategies suggested by the authorities?

- YES

- NO

- How much have you changed the way you live your life because of the possibility of continuing of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)?

- A GREAT DEAL

- A LOT

- A MODERATE AMOUNT

- A LITTLE

- NONE AT ALL

THANK YOU FOR TAKING OUR SURVEY

(Source: Revised and Adopted from WHO, 2020)