Version of Record (VoR)

Osuagwu, U. L., Nwaeze, O., Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G. O., Oloruntoba, R., Ekpenyong, B., Mashige, K. P., … Agho, K. E. (2021). Opinion and uptake of chloroquine for treatment of COVID-19 during the mandatory lockdown in the sub-Saharan African region. African Journal Of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v13i1.2795

Opinion and Uptake of Chloroquine for treatment of Coronavirus during the Mandatory Lockdown in Sub Sahara African Region

Abstract

Background: As the search for effective treatment of coronavirus infection (COVID-19) continues, the public opinion around the potential use of chloroquine in treating COVID-19 remain mixed.

Aim: To examine opinion and uptake of Chloroquine (CQ) for treating COVID-19 in Sub-Sahara African (SSA)

Methods: Anonymous online survey of 1829 SSAs was conducted during the lockdown using Facebook, WhatsApp and authors’ networks. Opinion and uptake of CQ for COVID-19 treatment were assessed using multivariate analyses.

Results: About 14% of respondents believed that CQ could treat COVID-19 and of which, 3.2% took CQ for COVID-19 treatment. Multivariate analyses revealed that respondents from Central (adjusted odds ratios (AOR): 2.54, 95%CI 1.43, 4.43) and West Africa (AOR: 1.79, 95%CI 1.15, 2.88) had higher odds of believing that CQ could treat COVID-19. Respondents from East Africa reported higher odds for uptake of CQ for COVID-19 than Central, Western and Southern Africans. Knowledge of the disease and compliance with the public health advice were associated with both belief and uptake of CQ for COVID-19 treatment.

Conclusions: Central and West African respondents were more likely to believe in CQ as a treatment for COVID-19 while the uptake of the medication during the pandemic was higher among East Africans. Future intervention discouraging the unsupervised use of CQ should target respondents from Central, West and East African regions.

Keywords: Coronavirus; sub-Saharan Africa; chloroquine hydrochloride; Africa; poisoning

Introduction

Global public health authorities must combat dangerous and unproven theories about the use of the antimalarial, chloroquine (CQ), for treating COVID-19 infections despite lack of evidence. Since the declaration of COVID-19 pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 11th, 20201, vaccines are now being introduced in different countries for treatment of the infection2 but their effectivity is still in test.3 Aware that novel treatments and/or vaccines will take time to be distributed to patients, there is growing interest in the use of existing medications, such as CQ and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), as potential treatments of COVID-19.4-7 Despite promising in vitro results8, there is no direct supporting data on the effective role of CQ and HCQ in the treatment for COVID-19.9 Those reporting that the drug has a favorable effect on the outcomes of COVID-19 were not clinical trials and used poor methodology.5, 6, 10, 11,12

CQ and its analogue, HCQ are considered safe and have side effects that are generally mild and transitory. However, there is a narrow margin between the therapeutic and toxic dose, and CQ poisoning has been associated with life-threatening cardiovascular disorders and 13 irreversible blindness from CQ retinopathy.14 Also, treatment with HCQ has been associated with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York State.1 CQ is proven effective as an antimalarial, amoebicide and antirheumatic, and its possible adverse reactions are well documented15. The use of this medication outside of these conditions should be appropriately monitored in the hospital as required by the Emergency Usage Authorization (EUA) or in a clinical trial with appropriate screening and monitoring.16, 17

Early on in the pandemic, the media environment was awash with misinformation concerning the use of chloroquine in the treatment of the COVID-19 infection. Layered on top of this was the retraction on June 4th, 2020 of the Lancet paper, which claimed that treating COVID-19 with the antimalarial drug raised the heart-related death risk for COVID-19 patients in the hospital without showing any benefit.18 The study was the basis for the halt of many studies of the antimalarial by WHO. The indiscriminate promotion of this medication by those in authority and widespread use of CQ in Africa has led to extensive shortages, self-treatment, and fatal overdoses.19 The shortages and increased market prices of this medication left the already weak health systems in Africa vulnerable to substandard and falsified medical products.17 Governments in SSA countries are “strongly considering” putting prescription monitoring programs in place to ensure that off-label use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine is appropriate and beneficial for COVID-19 patients.17

Considering the public-health emergency nature of COVID-19 and the new challenges of the second wave in SSA20, it is necessary to investigate the perception and behavior of Africans regarding CQ use for COVID-19. This study sought the opinions of people from SSA about the belief that CQ can cure COVID-19, and the influence of such a belief on their behavior by purchasing the medication to treat the infection and the factors associated with these variables. This study assessed the relationship between respondents' belief and use of CQ as a cure for COVID-19 and the compliance to the mitigation practices put in place by the respective governments to limit the spread of the virus. The findings are important for planning strategies for the control of COVID-19 and future outbreaks and will help to identify the population at greater risk of CQ abuse, which can be targeted to prevent complications as the pandemic still unfolds. Also, the findings will help to design interventions that will minimize the indiscriminate and/or unauthorized use of this medication among the population.

Methods

Study design

This self-administered web-based survey was conducted during the mandatory lockdown period (April 27th - May 17th, 2020) in most of the countries surveyed. It was not feasible to perform a nationwide community-based sample survey during the lockdown period, so data were obtained electronically through survey monkey. The questionnaire included a brief overview of the context, purpose, procedures, nature of participation, privacy and confidentiality statements and notes to be filled. Informed consent and permission to use de-identifiable information in the publication was obtained from the respondents. Information was sought on the respondents’ knowledge of the causes and symptoms of COVID-19 using the WHO validated tool.21 Respondents were also asked about their belief on the use of CQ for treatment of COVID-19, and if they had purchased and used CQ during the COVID-19 pandemic to avoid contracting the virus.

Prior to the launching of the survey, a pilot study was conducted to ensure clarity and understanding as well as to determine the duration for completing the questionnaire. Participants (n=10) who took part in the pilot were not part of the research team and did not participate in the final survey as well. This self-administered online questionnaire consisted of 58 items divided into four sections (demographic characteristics, knowledge, attitude, perception and practice).

Setting

The questionnaire was disseminated on social media platforms (Facebook and WhatsApp) commonly used by the locals in the participating countries. Emails sent to authors’ contacts and contact groups were also used by the researchers to facilitate response. On all platforms, recipients were encouraged to share the e-link of the survey with others.

Study population and sample size determination

Data was collected from four SSAs regions including Western, Eastern, Southern and Central Africa which consisted of people from Ghana, Cameroun (English speaking populations), Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Malawi, Rwanda etc. Classification of countries into regions was based on the regions of the African Union22. To be eligible for participation, participants had to be 18 years and over, able to read and understand English and should be able to provide online consent.

The study assumed a proportion of 50% because the main objective of this research was on COVID-19 and no previous study from SSA has examined factors associated with belief and uptake of CQ as a cure for COVID-19 during the pandemic. For expected proportion with 2.5% absolute precision and 90% confidence, an online sample size calculator23 determined that a sample size of approximately 1408 including 30% non-response rate was required to detect significant differences because it was an online survey. The sample size of 1829 participants used in this study is large enough to detect any statistical differences.

Independent variables

The independent variables included demographic (age, gender, marital status, country of origin (with Southern Africa as the base), education, employment and religion), practice (included compliance to mitigation practices of handwashing, self-isolation, quarantine and use of facemask when going out) and risk perception. Variables were summarized as counts and percentages for categorical variables.

Dependent variables

The dependent variables were the belief on the effectiveness of CQ for COVID-19 treatment, and purchase of the medication for COVID-19. Participants were asked the following questions: “Do you believe that COVID-19 can be cured by taking CQ tablets?” and “have you purchased CQ for COVID-19?”. Responses were categorized as "Yes" (1) or "No" (0).

Data analysis

All analyses were performed in Stata version 14.1 (Stata Corp 2015, College Station, Texas, USA). A two-way frequency table was used to obtain the prevalence estimates of those who believed that CQ could be used to treat COVID-19 and those who purchased the CQ. In the univariate analyses, odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated in order to assess the unadjusted risk of the independent variables on selected covariates. Multiple logistic regression analyses used pooled data of the four sub-regions and different key dependent variables to examine their relationship with the number of years of formal education of the respondents. Also, the logistic regression was used to determine whether any observed effect persisted in the presence of possible confounding variables. In addition, the study determined whether the acquisition of CQ was influenced by the respondent's knowledge and compliance with mitigation practices put in place to stop the spread of the infection. Details of the questions utilized to derive scores for knowledge; compliance with mitigation practices was presented in the supplementary table (S1).

TABLE 1: Descriptive statistics for socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge, risk perception and compliance to practices towards the coronavirus disease 2019 infection

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age category, in years (n = 1800) | ||

| 18–28 | 685 | 38.06 |

| 29–38 | 488 | 27.00 |

| 39–48 | 401 | 22.28 |

| 49+ | 226 | 12.56 |

| Sex (n = 1801) | ||

| Males | 1005 | 55.8 |

| Females | 796 | 44.00 |

| Sub-region (n = 1773) | ||

| West Africa | 999 | 56.4 |

| East Africa | 185 | 10.4 |

| Central Africa | 220 | 12.4 |

| Southern Africa | 369 | 20.8 |

| Employment status (n = 1809) | ||

| Employed | 1205 | 67.00 |

| Unemployed | 604 | 33.39 |

| Marital status (n = 1805) | ||

| Married | 802 | 44.43 |

| Not married | 1003 | 56.00 |

| Religion (n = 1806) | ||

| Christianity | 1596 | 88.37 |

| Others | 210 | 11.63 |

| Highest level of education (n = 1809) | ||

| Postgraduate degree (Masters/PhD) | 600 | 33.17 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 986 | 54.51 |

| Secondary/Primary | 223 | 12.33 |

| Profession | ||

| Non-healthcare sector | 1324 | 77.16 |

| Healthcare sector | 392 | 22.84 |

| Do you live alone during COVID-19 (n = 1807) | ||

| No | 1474 | 81.57 |

| Yes | 333 | 18.43 |

| Compliance | ||

| Practised self-isolation (n = 1792) | ||

| No | 1231 | 68.69 |

| Yes | 561 | 31.31 |

| Home quarantined because of COVID-19 (n = 1789) | ||

| No | 1084 | 60.59 |

| Yes | 705 | 39.41 |

| Worried about contracting the infection (n = 1829) | ||

| Very worried | 574 | 31.38 |

| Worried | 675 | 36.91 |

| Not worried | 580 | 31.71 |

| Knowledge of COVID-19 transmission† | ||

| Inadequate (0–2 points) | 1334 | 72.94 |

| Adequate (3–4 points) | 495 | 27.06 |

| Knowledge of symptoms‡ | ||

| Inadequate (0–6 points) | 1180 | 64.52 |

| Adequate (7–9 points) | 649 | 35.48 |

| Perception of risk of contracting the infection§ | ||

| Inadequate | 958 | 52.38 |

| Adequate | 871 | 47.62 |

| Compliance to mitigation practices | ||

| Low | 484 | 26.46 |

| Moderate | 1057 | 57.79 |

| High | 288 | 15.75 |

| N = 1829 COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PhD, Doctor of Philosophy. †, the maximum score was 4 points; ‡, maximum score was 9 points; §, maximum score was 24 points. Mitigation practices included those put in place by the African governments and included hand hygiene, use of facemasks, social distancing during the lockdown, not attending large gatherings including religious events. |

||

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval for the study was sought and obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the [name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process] (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process/HRP/HREC/2020/117). The study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration for Human Research. The confidentiality of participants was assured in that no identifying information was obtained from participants. The study adhered to the tenets of Helsinki's declaration, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to completing the survey. Participants were required to answer a 'yes' or 'no' to the consent question during survey completion to indicate their willingness to participate in this study.

Results

Characteristic of the sample

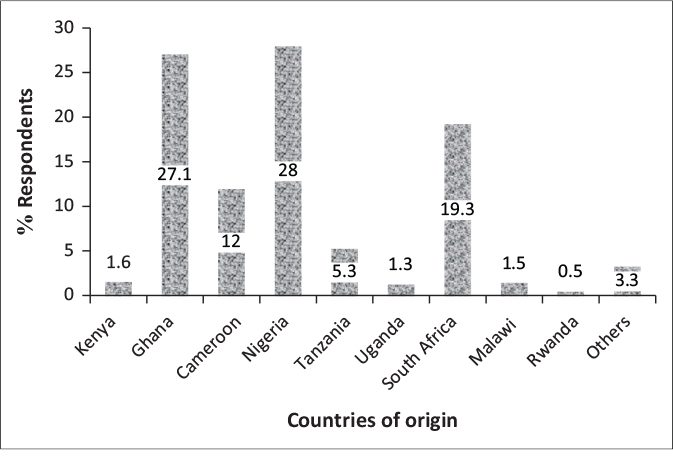

A total of 1829 adults responded to the outcome of interest in the survey and consisted of respondents from four SSA regions. Figure 1 shows the distribution of respondents by country of origin. The mean age was 26 years (range 18 – 50 years); many were aged 18-28 years (38.1%). More than half of the respondents were from Western Africa with a majority (91.3%) resident in their home country at the time of this study. Up to 87.7% had a university degree or higher education (Table 1). The majority were non-healthcare workers and did not live alone at the time of the COVID-19 lockdown.

FIGURE 1: Percentage distribution of the respondents by country of origin (n=1829) in sub-Saharan Africa

Most (68.7%) of the African respondents practiced self-isolation during the pandemic, while 60.6% were quarantined at the recommendation of health officers. Many respondents expressed some worry about contracting the virus and knowledge of the transmission and symptoms of the infection were generally inadequate among the respondents, as shown in Table 1.

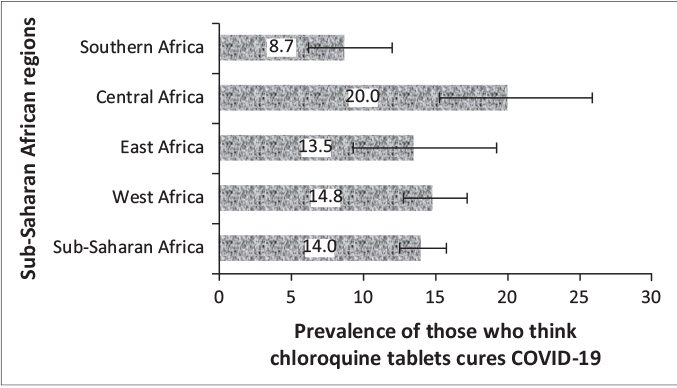

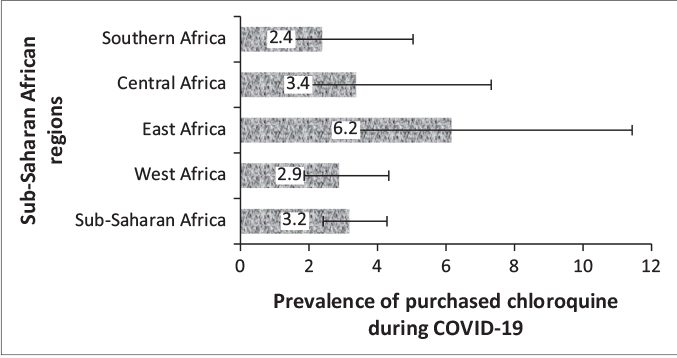

Prevalence of the belief and uptake of CQ for COVID-19 treatment during the pandemic

Figures 2 and 3 respectively show the prevalence and 95% CI of the belief in chloroquine as a cure for COVID-19 and uptake during COVID-19 pandemic for the four sub-regions, respectively. The prevalence of belief in CQ as a cure for COVID-19 was significantly higher in Central Africa (20, 95%CI: 15.2, 25.8) and lower in Southern Africa (9, 95%CI: 6.2, 12.0; p=0.001). Although there was higher uptake of CQ among East Africans during the pandemic, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.174). Of the 47 respondents in SSA who purchased CQ for COVID-19, nineteen of them (40.4%) did not believe that CQ was an effective treatment for COVID-19.

FIGURE 2: Prevalence and 95% confidence intervals of the belief in chloroquine tablets for the coronavirus disease 2019 treatment in sub-Saharan African regions.

FIGURE 3: Prevalence and 95% confidence intervals of chloroquine use for the coronavirus disease 2019 treatment in sub-Saharan African regions.

Univariate analysis

Table 2 presents the unadjusted odds ratios and 95%CI of perceived effectivity of CQ and uptake among respondents in this study. From the table, respondents living in Central Africa (unadjusted odds ratio, OR 2.63, 95%CI 1.61, 4.30) and West Africa (OR 1.83, 95%CI 1.22, 2.74) were more likely to believe that CQ can cure COVID-19, however, age and educational status were not associated with any of the outcome variables in this cohort. By contrast, no significant association was observed between the uptake of CQ for the COVID-19 treatment and any of the demographic variables. Belief in the use of CQ and its uptake during the pandemic were not dependent on whether the participants lived in their country of origin or outside their country of origin.

TABLE 2: Prevalence and unadjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for factors associated with belief and uptake of chloroquine tablets for treating the coronavirus disease 2019 and uptake in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in four sub-Saharan African regions.

| Variables | Perception | Uptake | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | OR | 95% CI | Prevalence | OR | 95% CI | |

| Sub-region | ||||||

| Southern Africa | 8.67 | 1.00 | - | 2.43 | 1.00 | - |

| Central Africa | 20.00 | 2.63 | 1.61–4.30 | 3.37 | 1.40 | 0.46–4.24 |

| East Africa | 13.51 | 1.65 | 0.94–2.87 | 6.16 | 2.64 | 0.96–7.23 |

| West Africa | 14.81 | 1.83 | 1.22–2.74 | 2.88 | 1.19 | 0.50–2.81 |

| Knowledge of COVID-19 | ||||||

| Transmission† | ||||||

| Inadequate | 8.92 | 1.00 | - | 2.99 | 1.00 | - |

| Adequate | 28.69 | 4.11 | 3.13–5.39 | 4.08 | 1.38 | 0.75–2.52 |

| Symptoms‡ | ||||||

| Inadequate | 14.92 | 1.00 | - | 3.41 | 1.00 | - |

| Adequate | 13.10 | 0.86 | 0.65–1.00 | 3.13 | 0.91 | 0.50–1.69 |

| Perception of risk of contracting the infection§ | ||||||

| Low risk (0–13) | 15.66 | 1.00 | - | 3.00 | 1.00 | - |

| High risk (14–24) | 12.74 | 0.79 | 0.60–1.03 | 3.64 | 1.22 | 0.68–2.19 |

| Compliance to mitigation practices | - | - | - | - | 1.00 | - |

| Low | 13.0 | 1.00 | - | 1.41 | 1.00 | - |

| Moderate | 13.5 | 1.05 | 0.76–1.44 | 3.37 | 2.44 | 0.95–6.37 |

| High | 19.1 | 1.58 | 1.06–2.34 | 6.01 | 4.47 | 1.59–12.60 |

| COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. Only variables with significant association are shown. Confidence intervals (CIs) excluding ‘1’ are statistically significant at p < 0.05 level; †, the maximum score was 4 points; ‡, maximum score was 9 points; §,maximum was 24 points. Mitigation practices included those put in place by the African governments and included hand hygiene, use of facemasks, self-isolation, social distancing during the lockdown, not attending large gatherings including religious events. |

||||||

Respondents who perceived CQ as a cure for COVID-19 were more likely to be those that demonstrated adequate knowledge of how the virus is transmitted (OR 4.11, 95%CI 3.13, 5.39). They were also more likely to highly comply with the mitigation practices (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.06, 2.34) put in place by the respective African governments to stop the spread of the virus during the pandemic. High compliance with the mitigation practices increased the odds of the demonstrated practice of purchasing CQ for treatment of COVID-19 by up to 4.5 folds compared to those who had poor compliance with the mitigation practices.

Multivariate analysis

Table 3 presents the multivariate analysis, which was adjusted for all potential cofounders. It was revealed that belief in the use of CQ for COVID-19 was predominant among respondents living in Central and West Africa, and was associated with adequate knowledge of the disease transmission (adjusted odds ratio, aOR 4.59, 95%CI 3.38, 6.23). By contrast, uptake of CQ during the pandemic was 3.18 folds (95%CI 1.02, 9.94) higher among East Africans than Southern Africans, after controlling for all the potential cofounders and was associated with high knowledge of the disease transmission and compliance with the mitigation practices during the outbreak.

TABLE 3: Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence intervals) of belief and uptake of chloroquine tablets for treating the coronavirus disease 2019.

| Variables | Perception | Uptake | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

| Sub-region | ||||

| Southern Africa | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Central Africa | 2.54 | 1.43–4.43 | 1.69 | 0.49–5.92 |

| East Africa | 1.61 | 0.85–2.93 | 3.18 | 1.02–9.94 |

| West Africa | 1.79 | 1.15–2.88 | 1.48 | 0.54–4.06 |

| Knowledge of COVID-19 | ||||

| Transmission† | ||||

| Inadequate | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Adequate | 4.59 | 3.38–6.23 | 2.03 | 1.04–3.97 |

| Symptoms‡ | ||||

| Inadequate | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Adequate | 0.89 | 0.65–1.22 | 1.13 | 0.58–2.21 |

| Compliance to mitigation practices | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Low | 1.13 | 0.77–1.65 | 2.23 | 0.75–6.62 |

| High | 1.56 | 0.96–2.55 | 4.33 | 1.30–14.40 |

| COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. Only variables with significant association are shown. Confidence intervals (CIs) excluding ‘1’ are statistically significant at p < 0.05 level; †, the maximum score was 4 points; ‡, maximum score was 9 points; §,maximum was 24 points. Mitigation practices included those put in place by the African governments and included hand hygiene, use of facemasks, self-isolation, social distancing during the lockdown, not attending large gatherings including religious events. |

||||

Discussion

This study provided the first comprehensive evidence on belief in the CQ controversy for COVID-19 treatment perception and behavior among the African population. It provides important knowledge to manage the evolving COVID-19 pandemic in the region. One in seven respondents believed that CQ can cure COVID-19, particularly Central and West Africans and those with adequate knowledge of the disease transmission. East Africans, and those that complied with the government mitigation practices, were also more likely to purchase CQ for COVID-19. The behavior to purchase CQ tablet for COVID-19 contradicts the WHO and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warnings against the use of chloroquine for COVID-19.16, 17

The belief that CQ could cure COVID-19 and therefore be used indiscriminately for same may be impacting on the lives of others who depend on CQ for the approved uses.24 As shown in this study, more than two-thirds of those who purchased CQ did not believe in its use for COVID-19 treatment suggesting they may have bought the medication just for stocking to avoid possible future market shortage of the drug should it be proven that it was effective in treating COVID-19. Storage of the medication was already causing shortages across the region and had the potential to further increase the panic among those who depend on this medication for their medical conditions.19 The finding that people with adequate knowledge of the disease transmission were more likely to purchase CQ may be as a result of information overload and medication misinformation regarding cures for COVID-19 that have been shown to spread unnecessary fear and panic leading members of the public to undermine legitimate public health advice.25 Majority of the respondents were young people, were more likely to have internet access, and maybe more exposed to the media, which may not necessarily translate into an increase in actual knowledge. Exposure to the media might enhance the impression of one’s knowledge or self-perceived knowledge, as reported previously.26 Identifying this group of people and discouraging them from indiscriminate use of CQ certainly becomes a responsible public health approach.

The belief and uptake of CQ among the respondents may have also been encouraged by the socio-behavioral factors of familiarity with the drug and its perceived efficacy.27 This may explain the lack of association between the outcome variables and educational level in this study. Interestingly, we also found that those who were highly compliant with the government regulations to stop the spread of the disease were also more likely to endorse the CQ misinformation. This finding contrasts with those who believe in conspiracy theories such as the origin of the disease and vaccine efficacy who have been found to be less likely to be compliant to government regulations. 28, 29,30 The former is more likely driven by fear of contracting the disease while the latter is driven by mistrust.

The CQ controversy became the focus of global scientific, media, and political attention after a French virologist, went public on social media to promote the use of chloroquine to treat or prevent COVID-19.31 His opinion was widely picked up by people across the globe, and many demanded immediate chloroquine for all.32 Despite other studies that have shown that CQ may not be as efficacious as claimed especially in severe cases,33-35 it still resulted in a scarcity for those who are on CQ/HCQ for legitimate indications such malaria and lupus. According to WHO guidelines, CQ is restricted and strictly reserved for severe malaria and special cases of uncomplicated malaria in patients allergic to other drugs36.37 Although, CQ has been removed as a first line treatment regimen for malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum in SSA countries,38 it is still available as an over the counter (OCT) medicine in many of them.31, 36 The fear of contracting the disease as seen in 68% of the respondents who were ‘worried about contracting COVID-19’ may have driven people to buy whatever the media promotes as a cure for the disease. This behavior has spread beyond CQ to include zinc supplements, aspirin, vitamin C and azithromycin.39

Generally considered safe for the well-known approved indications in Africa, intake of CQ has been associated with severe adverse effects in COVID-19. Patients with underlying health issues, such as heart and kidney disease, are more likely to be at increased risk of experiencing heart problems when taking CQ and HCQ according to the FDA.40 This becomes more disturbing in Africa where many have underlying diseases they are unaware of due to poor health systems and or lack of proper screening programs. With this in mind, and in the light of recent evidence that CQ and HCQ are not effective for the treatment of COVID-199, this study will guide SSA countries in formulating temporary prescription guidelines and restrictions around CQ usage. One way of doing this is through legislation of CQ/HCQ as prescription-only-medication and making it available to designated pharmacies within regions. In effect, with CQ/HCQ as prescription-only-medicine, physicians would be ‘forced’ professionally to state the actual indication for any prescriptions given. The current frontline drugs for malaria are the artemisinin based combination therapies (ACTs) which are also over the counter prescriptions.41 These medications can be subsidized for this period by governments to make them accessible to the populace.42 This study also recommends that physicians should place some emphasis on medication history of their patients to identify those who do not need the medication but are taking it, as well as using such encounters to counsel patients on medication safety and associated adverse effects. More importantly, the present finding would encourage concerted health promotional activities through campaigns at various governmental levels on educating the people on the dangers of self-medication through radio and TV as well as via the commonly used social media platforms in each country. The media strategy was effective during the swine flu outbreak.43 Series of public service announcements can be crafted, and made available in both English and French to increase awareness of the COVID-19. Such announcements should encourage testing and medical check for symptomatic patients, through emphasis on the benefits of testing, overcoming drug misinformation and increasing people’s perceptions of their own ability to control the spread of the disease.

Formal education most often teaches basic reading skills, enlightens, and aids in removing some of the cultural ideologies that lead to the misconceptions that affect proper and adequate prevention and treatment of diseases. Although studies in Africa have shown a significant association between higher levels of education and positive knowledge, attitude and practice towards diseases like malaria,44 as well as with recognition and appropriate treatment of diseases,45,46 we found no association between level of education and both perception and uptake of CQ for COVID-19. This was despite the fact that in this study there was a preponderance of highly educated people in this study, though not reflective of the general population of the region.

Strengths and limitations

First, the survey was only administered online. It may not have captured the opinion of those in rural areas where internet penetration remains relatively low47 and older people who are less likely to use internet compared to younger ones. Since the increase in public interest during the pandemic resulted in greater internet use,48 this may not have a great impact on the findings coupled with the fact that it was the only reliable means to disseminate information at the time of this study. This was also an innovative way to provide real-time data on the current situation. Second, the survey was available only in English, making it impossible for some SSA francophone countries to participate, and the result may not be generalizable to all Sub-Saharan Africa population because of the sampling technique. Thirdly, there were wide variations in the response rate per region, which may be due to population differences and poverty levels that influence access to internet. Fourthly, the lack of incentive and not receiving assistance with any online company for distribution of the survey may have affected the reach of the survey. It also meant that the social media accounts could not be verified and those with multiple accounts could not be eliminated. The questionnaire however appealed to respondents not to fill the questionnaire more than once and the platform prevented respondents from submitting more than one response from the same account. Lastly, although the sample size was adequate to detect statistical differences, some CIs were stretched, suggesting that the study may benefit from a much bigger sample. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to provide evidence of the CQ controversy during the pandemic while controlling the potential confounders during the analysis. Another advantage of our survey is that it was collected when the restrictions were the strictest in the concerned countries. Data collection method was the same across the countries, and people answered on a voluntary basis. Beyond the reduced cost, another key advantage of online surveys is that the questionnaire is available to a great number of people, at any time of the day; also, the data can be processed in real-time.

Conclusion

In summary, the world faces imperatives to combat dangerous misinformation around COVID-19. In the absence of a known effective therapy, the possibility of a second wave of COVID-19 or another potential public-health emergency, this first population-based survey provided evidence of an avoidable danger of CQ abuse and its associated complications, particularly among East Africans. The gross inadequate knowledge and increasing worry shown by Africans in this study suggest the need for regional educational intervention to create awareness and sensitize the public on COVID-19 transmission as well as re-orientate the communities on the dangers of indiscriminate use of CQ during the pandemic. Pharmaco-medical control should be imposed on the acquisition of CQ by governments to control abuse. Public health officers and clinicians have roles to play in discouraging this attitude by highlighting the non-proven use of CQ in treating COVID-19. There is a risk that Africans who resort to CQ might not follow up on legitimate COVID-19 symptoms with their doctors, which in turn, could facilitate the spread of the virus and put their health, and potentially that of others, at risk.

Funding: This research did not receive any funding.

Data Availability: Data is available on reasonable request from the corresponding author

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

-

Rosenberg ES, Dufort EM, Udo T, Wilberschied LA, Kumar J, Tesoriero J et al. Association of treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York state. Jama. 2020;323:2493-2502. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.8630

-

Le TT, Andreadakis Z, Kumar A, Román RG, Tollefsen S, Saville M et al. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:305-306. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41573-020-00073-5

-

De-Leon H, Calderon-Margalit R, Pederiva F, Ashkenazy Y, Gazit D. First indication of the effect of COVID-19 vaccinations on the course of the COVID-19 outbreak in Israel. medRxiv. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.02.21250630

-

Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends. 2020;14:72-73. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2020.01047

-

Chen Z, Hu J, Zhang Z. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: results of a randomized clinical trial. MedRiv. 2020;10:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.22.20040758

-

Dandan Y, Zhan Z. Therapeutic effect of hydroxychloroquine on novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19). In: Registry CCT, editor. 2020. http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx

-

Huang M, Tang T, Pang P, Li M, Ma R, Lu J et al. Treating COVID-19 with Chloroquine. J Mol Cell Biol. 2020;12:322-325. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmcb/mjaa014

-

Colson P, Rolain J-M, Raoult D. Chloroquine for the 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105923

-

Gasmi A, Peana M, Noor S, Lysiuk R, Menzel A, Gasmi Benahmed A et al. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19: the never-ending story. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2021;105:1333-1343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-021-11094-4

-

Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Bioscience trends. 2020;14:72-73. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2020.01047

-

Huang M, Tang T, Pang P, Li M, Ma R, Lu J et al. Treating COVID-19 with Chloroquine. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. 2020;12:322-325. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmcb/mjaa014

-

Guastalegname M, Vallone A. Could Chloroquine /Hydroxychloroquine Be Harmful in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment? Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:888-889. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa321

-

Frisk-Holmberg M, Bergqvist Y, Englund U. Chloroquine intoxication [letter]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;15:502-503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb01540.x

-

Lotery A, Burdon M. Monitoring for hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Eye. 2020;34:1301–1302. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-0795-2

-

PubChem Compound Summary for CID 2719, Chloroquine. In: Information NCfB, editor. MD, USA: USA.gov; 2020. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Chloroquine

-

FDA: Do not use malaria drugs to treat COVID-19 except in trials, hospitals [press release]. American Academy of Pediatrics April 24 2020. Available at: https://www.aappublications.org/news/2020/04/24/covid19drugwarning042420

-

Abena PM, Decloedt EH, Bottieau E, Suleman F, Adejumo P, Sam-Agudu NA et al. Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine for the Prevention or Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Africa: Caution for Inappropriate Off-Label Use in Healthcare Settings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102:1184-1188. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0290

-

Hiltzik M. How a retracted research paper contaminated global coronavirus research. The Los Angeles Times. 2020 June 8;Sect. Media coverage of health and science topics. https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2020-06-08/coronavirus-retracted-paper

-

Rosenberg ES, Dufort EM, Udo T, Wilberschied LA, Kumar J, Tesoriero J et al. Association of Treatment With Hydroxychloroquine or Azithromycin With In-Hospital Mortality in Patients With COVID-19 in New York State. JAMA. 2020;323:2493-2502.

-

Kuehn BM. Africa Succeeded Against COVID-19’s First Wave, but the Second Wave Brings New Challenges. Jama. 2021;325:327-328. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.24288

-

WHO. Survey tool and guidance: behavioural insights on COVID-19. In: Organization WH, editor. Copenhagen: WHO Regional office for Europe; 2020. p. 1-44.

-

Strengthening popular participation in the African Union: a guide to AU structures and processes: Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA) and Oxfam; 2009.

-

NK D, MS K. Statulator: an online statistical calculator—sample size calculator for estimating a single mean 2014 [Available from: http://statulator.com/SampleSize/ss1P.html.

-

Dreisbach EN. Off-label hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine use for COVID-19 poses threat to Africa. Infectious Disease. 2020 May 07, 2020.

-

Erku DA, Belachew SA, Abrha S, Sinnollareddy M, Thomas J, Steadman KJ et al. When fear and misinformation go viral: Pharmacists' role in deterring medication misinformation during the 'infodemic' surrounding COVID-19. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020.

-

Park C-Y. News media exposure and self-perceived knowledge: The illusion of knowing. Int J Public Opin Res. 2001;13:419-425. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/13.4.419

-

Le Grand A, Hogerzeil HV, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Intervention research in rational use of drugs: a review. Health Policy Plan. 1999;14:89-102. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/14.2.89

-

Jolley D, Douglas KM. Prevention is better than cure: addressing anti‐vaccine conspiracy theories. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2017;47:459-469. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12453

-

Jolley D, Douglas KM. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PloS one. 2014;9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089177

-

Freeman D, Waite F, Rosebrock L, Petit A, Causier C, East A et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychol Med. 2020:1-30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001890

-

Gautret P, Lagier J-C, Parola P, Meddeb L, Mailhe M, Doudier B et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2020:105949.

-

Abboud L. Marseille’s maverick chloroquine doctor becomes pandemic rock star. Financial Times. 2020 Apr 3.

-

Ferner RE, Aronson JK. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in covid-19. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2020.

-

Zhai P, Ding Y, Wu X, Long J, Zhong Y, Li Y. The epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2020:105955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105955

-

Lagier J-C, Million M, Gautret P, Colson P, Cortaredona S, Giraud-Gatineau A et al. Outcomes of 3,737 COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine/azithromycin and other regimens in Marseille, France: A retrospective analysis. Travel medicine and infectious disease. 2020;36:101791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101791

-

Organization WH. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria: World Health Organization; 2015.

-

Kayentao K, Florey LS, Mihigo J, Doumbia A, Diallo A, Koné D et al. Impact evaluation of malaria control interventions on morbidity and all-cause child mortality in Mali, 2000-2012. Malar J. 2018;17:424-424. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2573-1

-

Balikagala B, Sakurai-Yatsushiro M, Tachibana S-I, Ikeda M, Yamauchi M, Katuro OT et al. Recovery and stable persistence of chloroquine sensitivity in Plasmodium falciparum parasites after its discontinued use in Northern Uganda. Malar J. 2020;19:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-020-03157-0

-

Cortegiani A, Ingoglia G, Ippolito M, Giarratano A, Einav S. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. Journal of Critical Care. 2020;57:279-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005

-

Food U, Administration D. FDA cautions against use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for COVID-19 outside of the hospital setting or a clinical trial due to risk of heart rhythm problems. 2020.

-

Pousibet-Puerto J, Salas-Coronas J, Sánchez-Crespo A, Molina-Arrebola MA, Soriano-Pérez MJ, Giménez-López MJ et al. Impact of using artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria from Plasmodium falciparum in a non-endemic zone. Malaria journal. 2016;15:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1408-1

-

Sawadogo C, Amood Al-Kamarany M, Al-Mekhlafi H, Elkarbane M, Al-Adhroey A, Cherrah Y et al. Quality of chloroquine tablets available in Africa. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology. 2011;105:447-453. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.873363

-

Jones CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL, Brown NR, Christy K, Weaver J. The health belief model as an explanatory framework in communication research: Exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Commun. 2015;30:566-576. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.873363

-

Njama D, Dorsey G, Guwatudde D, Kigonya K, Greenhouse B, Musisi S et al. Urban malaria: primary caregivers’ knowledge, attitudes, practices and predictors of malaria incidence in a cohort of Ugandan children. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:685-692. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01060.x

-

Sirima SB, Konate A, Tiono AB, Convelbo N, Cousens S, Pagnoni F. Early treatment of childhood fevers with pre‐packaged antimalarial drugs in the home reduces severe malaria morbidity in Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:133-139. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.00997.x

-

Abir T, Kalimullah NA, Osuagwu UL, Yazdani DMN-A, Mamun AA, Husain T et al. Factors Associated with the Perception of Risk and Knowledge of Contracting the SARS-Cov-2 among Adults in Bangladesh: Analysis of Online Surveys. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020;17:5252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145252

-

Hjort J, Poulsen J. The arrival of fast internet and employment in Africa. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109:1032-1079. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161385

-

Effenberger M, Kronbichler A, Shin JI, Mayer G, Tilg H, Perco P. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic with Internet Search Volumes: A Google TrendsTM Analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:192-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.033

Supplementary table 1: COVID-19 knowledge and practice survey in Africa

CONSENT/BASIC DESCRIPTION

CONSENT

- I willingly agree to participate in this survey because I am interested in contributing to the knowledge and perceptions on Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemia. I understand that there are no forms of payments or reward associated with my participation.

- UNDERSTOOD, AGREE AND INTERESTED

- NOT UNDERSTOOD, DISAGREE AND NOT-INTERESTED

- Country of origin

- Country of residence

- Province/State/County

- Gender

- MALE

- FEMALE

- OTHERS

- Age (Years)

- Marital Status

- SINGLE

- MARRIED

- SEOARATED/DIVORCED

- WIDOW/WIDOWER

- Religion

- MUSLIM

- CHRISTIAN

- AFRICAN TRADITIONALIST

- OTHERS

- Highest level of education

- PRIMARY SCHOOL

- HIGH/SECONDARY SCHOOL

- POLYTHECNIC/DIPLOMA

- UNIVERSITY DEGREE (Bachelors/Professional)

- POSTGRADUATE DEGREE (Masters/PhD)

- Employment Status

- SELF EMPLOYED

- EMPLOYED

- UNEMPLOYED

- STUDENT/NON-STUDENT

- Occupation

- Do you live alone?

- YES

- NO

- If you live with family/friends, how many of you live together?

General KNOWLEDGE of COVID-19 Origin and outbreak

- Are you aware of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak?

- YES

- NO

- Are you aware of the origin of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak?

- YES

- NO

- Do you think Coronavirus disease (C0VID-19) outbreak is dangerous?

- YES

- NO

- Do you think Public Health Authorities in your country are doing enough to control the Coronavirus disease (C0VID-19) outbreak?

- YES

- NO

- Do you think Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has little effect(s) on Blacks than on Whites?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

KNOWLEDGE OF PREVENTION

- Do you think Hand Hygiene / Hand cleaning is important in the control of the spread of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- Do you think ordinary residents can wear general medical masks to prevent the infection by the COVID-19 virus?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- Do you think Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is associated with 5G communication?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- Do you think antibiotics can be effective in preventing Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- If yes to Q22 above, have you purchased an antibiotic in response to COVID-19 disease outbreak?

- YES

- NO

- Do you think there are any specific medicines to treat Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- Do you think there would be a vaccine for preventing Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in the next 6 months?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- Do you think Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was designed to reduce world population?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

Knowledge of symptoms

- The main clinical symptoms of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) are: (Type "YES" or "NO" to the suggested options as applicable)

- FEVER

- FATIGUE

- DRY COUGH

- SORE THROAT

- Unlike the common cold, stuffy nose, runny nose, and sneezing are less common in persons infected with the COVID-19 virus.

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- There currently is no effective cure for COVID-2019, but early symptomatic and supportive treatment can help most patients recover from the infection

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- It is not necessary for children and young adults to take measures to prevent the infection by the COVID-19 virus.

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- COVID-19 individuals cannot spread the virus to anyone if there's no fever.

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- The COVID-19 virus spreads via respiratory droplets of infected individuals

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

Knowledge of prevention

- To prevent getting infected by Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), individuals should avoid going to crowded places such as train stations, religious gatherings, and avoid taking public transportation

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- Isolation and treatment of people who are infected with the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) virus are effective ways to reduce the spread of the virus. The observation period is usually 14 days

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- Not all persons with COVID-2019 will develop to severe cases. Only those who are elderly, have chronic illnesses, and are obese are more likely to be severe cases.

- TRUE

- FALSE

- NOT SURE

- Have you or anyone you know been affected by the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in any way(s)?

- YES

- NO

- If Yes to Q36 above, how did the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) affect you or that person you know? (Type "YES" or "NO" as applicable to the listed effects)

- LOST JOB

- LOST/CLOSED DOWN BUSINESS

- CONTRACTED COVID-19

- HOSPITALIZED DUE TO COVID-19

- COMPLETELY SEPARATED FROM FAMILY

- COMPLETELY STRANDED IN A FOREIGN COUNTRY/AWAY FROM REGULAR HOME/IN A DIFFERENT LOCATION FROM USUAL LOCATION OF RESIDENT

PERCEPTION OF RISK OF INFECTION

- Risk of becoming infected.

- VERY HIGH

- HIGH

- LOW

- VERY LOW

- UNLIKELY

- Risk of becoming severely infected

- VERY HIGH

- HIGH

- LOW

- VERY LOW

- UNLIKELY

- Risk of dying from the infection

- VERY HIGH

- HIGH

- LOW

- VERY LOW

- UNLIKELY

- How worried are you because of COVID-19?

- A GREAT DEAL

- A LOT

- A MODERATE AMOUNT

- A LITTLE

- NONE AT ALL

- How do you feel about the self-isolation? (Type "YES" or "NO" to the suggested options as applicable)

- WORRIED

- BORED

- FRUSTRATED

- ANGRY

- ANXIOUS

- I consider the self-isolation as necessary and reasonable

- STRONGLY AGREE

- AGREE

- NEITHER AGREE, NOR DISAGREE

- DISAGREE

- STRONGLY DISAGREE

- Do you think that if you are able to hold your breath for 10 seconds, it's a sign that you don't have COVID-19?

- YES

- NO

- NOT SURE

- If you drink hot water, it flushes down the virus

- STRONGLY AGREE

- AGREE

- NEITHER AGREE, NOR DISAGREE

- DISAGREE

- STRONGLY DISAGREE

- How likely do you think Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) will continue in your country?

- VERY LIKELY

- LIKELY

- NEITHER LIKELY, NOR UNLIKELY

- UNLIKELY

- VERY UNLIKELY

- If Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues in your country, how concerned would you be that you or your family would be directly affected?

- EXTREMELY CONCERNED

- CONCERNED

- NEITHER CONCERNED, NOR UNCONCERNED

- UNCONCERNED

- EXTREMELY UNCONCERNED

PRACTICE REGARDIING COVID-19

- In recent days, have you gone to any crowded place including religious events?

- ALWAYS

- SOMETIMES

- RARELY

- NOT AT ALL

- NOT SURE

- In recent days, have you worn a mask when leaving home?

- ALWAYS

- SOMETIMES

- RARELY

- NOT AT ALL

- NOT SURE

- In recent days, have you been washing your hands with soap and running water for at least 20 seconds each time?

- ALWAYS

- SOMETIMES

- RARELY

- NOT AT ALL

- NOT SURE

- Are you currently or have you been in (domestic/home) quarantine because of COVID-19?

- YES

- NO

- Are you currently or have you been in self-isolation because of COVID-19?

- YES

- NO

- Since the government gave the directives on preventing getting infected, have you procured your mask and possibly sanitizer?

- YES

- NO

- Have you travelled outside your home in recent days using the public transport

- YES

- NO

- Are you encouraging others that you come in contact with to observe the basic prevention strategies suggested by the authorities?

- YES

- NO

- How much have you changed the way you live your life because of the possibility of continuing of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)?

- A GREAT DEAL

- A LOT

- A MODERATE AMOUNT

- A LITTLE

- NONE AT ALL

THANK YOU FOR TAKING OUR SURVEY