Version of Record (VoR)

Envuladu, E. A., Miner, C. A., Oloruntoba, R., Osuagwu, U. L., Mashige, K. P., Amiebenomo, O. M., … Agho, K. E. (2022). International research collaboration during the pandemic : team formation, challenges, strategies and achievements of the African Translational Research Group. International Journal Of Qualitative Methods, 21, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221115504

International research collaboration during the pandemic:

Team formation, challenges, strategies and achievements of the African Translational Research Group (ATReG)

Esther Awazzi Envuladu1, Chundung Asabe Miner1, Richard Oloruntoba ![]() 2, Uchechukwu Levi Osuagwu

2, Uchechukwu Levi Osuagwu ![]() 3,4, Khathutshelo P. Mashige3, Onyekachukwu M. Amiebenomo

3,4, Khathutshelo P. Mashige3, Onyekachukwu M. Amiebenomo ![]() 5,6, Emmanuel Kwasi Abu7, Chikasirimobi G. Timothy8, Godwin Ovenseri-Ogbomo

5,6, Emmanuel Kwasi Abu7, Chikasirimobi G. Timothy8, Godwin Ovenseri-Ogbomo![]() 9, Bernadine N. Ekpenyong3,10, Raymond Langsi11, Piwuna Christopher Goson12, Deborah Donald Charwe13, Tanko Ishaya14, and Kingsley Emwinyore Agho

9, Bernadine N. Ekpenyong3,10, Raymond Langsi11, Piwuna Christopher Goson12, Deborah Donald Charwe13, Tanko Ishaya14, and Kingsley Emwinyore Agho ![]() 3,4,15

3,4,15

Background

This paper discusses team formation, operational challenges, strategies, achievements, and dynamics in the implementation of research for the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), by the African Translational Research Group (ATReG), as well as the lessons learnt and future opportunities for global collaborative research.

Methods

In-depth virtual interviews were conducted with consenting members of ATReG. Questions were designed to provide rich, deep, and insightful subjective opinions, and lived experiences and perspectives of the group members on formation, challenges, and strategies and achievements. Data was transcribed and analysed thematically, and the results were presented with important quotations cited.

Findings

The ATReG consisted of English (n=13) and French (n=1) speaking sub-Saharan African (SSA) researchers who specialise in public health, epidemiology, optometry, information technology, supply chain management, psychiatry, community health, general medical practice, nutrition and biostatistics. Most members reported the informal but well-coordinated structure of the group. Formed during the pandemic, all meetings were held online, and some members have never met each other in person. The group collected data from Africans and published ten peer reviewed articles on COVID-19, presented in international conferences and were awarded a national competitive funding in Nigeria which contributed to career progressions and promotions of the members. There have been numerous challenges in sustaining the collaboration and maintaining productivity including meeting deadlines and obtaining funding for research activities. However, these challenges have been addressed through a collaborative problem-solving approach. The need for operational and methodological flexibility, central coordination and funding sources are essential for the group sustainability.

Conclusion

The ATReG’s objective of providing useful data on COVID-19 in SSA was achieved. In such a multi-disciplinary collaborative team, the experiences and challenges can be a model for researchers intending future collaborative groups. There remain numerous important areas for research which the ATReG will continue to pursue.

Keywords: Multidisciplinary; Research collaboration; COVID-19 pandemic; Sub-Sahara Africa

Introduction

In April of 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic raged, five public health researchers of African heritage agreed to collaboratively undertake timely translational public health research concerning COVID-19 in African countries. Two members of the group have affiliation to an Australian University public health department, while three members were affiliated to various public health and medical departments at South African and Nigerian universities. Within a period of eight months, the international research collaboration grew by invitation to a membership of 14 African researchers working in various universities and research institutions spanning Australia, Cameroun, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Tanzania, and the United Kingdom. The group adopted the name ‘African Translational Research Group (ATReG)’.

The consensus goal of this international, multicultural, multi-lingual and multidisciplinary collaborative research team was to: work as a collaborative group of African researchers by bringing in expertise from their various disciplines, resources and knowledge of their country’s culture and language with respect to research and data collection, in mitigating the effects of the pandemic particularly in African countries. The team sought to provide evidence-based information that could be used to drive decision-making and health policy thereby, reducing the impact of the pandemic and its control measures. It also sought to undertake knowledge exchange activities between African researchers in the Diaspora and those in the African countries based on the peculiarities found in the different settings. The pandemic was a great opportunity for such cross-sector partnership which have been shown to help create and deliver value in response to health emergencies, like the COVID-19 pandemic, and in turn help with adaptive learning (Arslan, Golgeci, Khan, Al-Tabbaa, & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, 2020; Vervoort, Ma, & Luc, 2021). A review of the emergency response in the United States demonstrated that the involvement of stakeholders where partnerships for resources, expertise and knowledge are built between state and non-state actors from different sectors, but functioning in a non-hierarchical manner, produced better outcomes. (Demiroz, Fatih & Kapucu, Naim. 2015; Yu Z, Xu, & Yu, L, 2022).

Furthermore, this collaborative team could drive empirical research from an African perspective and report on the outcomes of such research in a range of academic and non-academic outlets such as international journals, conferences, health policy outlets, and the general media. ATReG also aimed to engage with public health and COVID-19 policymakers. In doing so, the team sought to achieve its aim of translating research findings to be of use to academicians, laypersons and policy makers in making decisions towards control of the epidemic. This aligns with the goal of translation research to “translate (move) basic science discoveries more quickly and efficiently into practice”. It does this by promoting multidisciplinary collaboration, incorporating the desires of the public and identifying and supporting adoption of best medical and health practices (Rubio et al 2010; Li & Yu, 2022). The formation of the team, the challenges it overcame and the recorded achievements were significant and timely giving the ongoing global challenges of the pandemic, particularly in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. In a health policy article that explored multilateral collaboration between countries during infectious disease outbreaks, the authors (Jit et al., 2021) suggested that responding to future global infectious disease threats and other health emergencies will require the creation of stronger mechanisms for multilateral collaboration before they arise(Jit et al., 2021). This should be done through cooperation agreements driven by major research funders and harmonising research findings to avoid duplication.

Overview synthesis of the literature on international research collaboration

Research collaboration between individuals, groups, departments, institutions, regions, and countries is a growing activity that has attracted the attention of researchers from several fields including those in natural sciences, medicine, communication technology, and software engineering (Fry, Cai, Zhang, & Wagner, 2020; Kwiek, 2021). With a diverse expansion of the literature on research collaboration, there have been several studies in this domain (Bozeman & Boardman, 2014; Kwiek, 2021). Previous publications have identified several clusters of research collaborations, ranging from inter-individual research collaboration(Nyström, Karltun, Keller, & Andersson Gäre, 2018) to inter-departmental and inter-institutional collaborations(Hedges et al., 2021). Driven by increasing global economic competition and rapid technological changes, more countries consider cross-country collaboration in science and technology a critical way to foster and maintain global innovation and economic competitiveness (Glänzel, 2001). A country with more cross-country collaborative linkages is able to leverage the domestic capabilities and exploit foreign investments in research and development (R&D) and commercialisation opportunities(Wagner, 2009). Thus, international research collaboration is perceived as a dominant driving force for promoting scientific and technological advancement(Wang, Rodan, Fruin, & Xu, 2014), industrial innovation, and economic growth(Sharma & Thomas, 2008). Furthermore, in scientific and technological research domains, the growing scale of research projects and complexity, particularly in projects that are set up to address important global challenges (e.g., COVID-19, energy crisis and climate change), are often beyond the capabilities of individual countries, hence significant interest in international research collaboration activities is necessary (D’ippolito & Rüling, 2019). The literature on international research collaboration is on a steady increase, while some studies have examined the factors that trigger cross-country research collaboration (Plotnikova & Rake, 2014), others have explored international research collaboration in higher education (Milman, 2021; Taras et al., 2013), its structures and team dynamics (Bagshaw, Lepp, & Zorn, 2007; Garg & Padhi, 2001). It is also important to understand who researchers choose to collaborate with (Iglič, Doreian, Kronegger, & Ferligoj, 2017) including industry or university research collaborations(Mascarenhas, Ferreira, & Marques, 2018), as well as the effects of such international research collaborations (Ernberg, 2019). The dramatic growth of international research collaborative studies in recent times, makes this paper necessary and conducive to a nuanced understanding of our particular research domain, the difficult context of the pandemic in which this collaboration was hastily formed, and how trust was developed very quickly resulting in several successful research outcomes (Berger, Doherty, Rudol, & Wzorek, 2021; Yu, Shen, & Khazanchi, 2021; Zakaria & Yusof, 2020). The unique characteristics of the inter-individual international research collaboration make this study different from that of other domestic research collaborations. A robust understanding of the field of international research collaboration in any discipline is necessary. The geographic, linguistic, political, cultural distances or gaps are more significant than those in other kinds of research collaboration (Chen, Zhang, & Fu, 2019; Cheng et al., 2016; Fu & Li, 2016). Moreover, the capabilities and motivations for international research collaboration may affect the patterns, effects, and outcomes of international research collaboration. Such differences are pronounced when research collaboration expands to individual researchers in several countries across Africa, UK, and Australia. Therefore, the patterns, team dynamics, processes and effects of such inter-individual international research collaboration demonstrates unique features that are yet to be analysed in other international research collaboration studies. To fill this research gap, a case study was conducted based on collaborative team processes and dynamics in the implementation of COVID-19 related empirical research in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries during the lockdowns that were enforced in many African countries, as well as lessons learnt that could be adopted by researchers seeking to collaborate anywhere in the world.

Methodology and interview analysis strategies

Interview guide and consent

The interview guide was developed by an independent researcher – an expert in qualitative research who was not a member of the group at the time. The guide was based on the information provided on the activities of the group. This was reviewed and pre-tested before the actual interview was conducted. A written and/or verbal informed consent was obtained from participating members before the commencement of the interview, basic biographical data of the members was asked followed by questions focused on the composition, strategies, success stories and achievements of the groups, as well as the challenges and recommendations. Approval for this study was obtained from the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (approval#: HSSREC 00002504/2021) of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. The study adhered to the principles of the 1967 Helsinki declaration (as modified in Fortaleza 2013) for research involving human subjects. The confidentiality of participant responses was assured, and anonymity maintained.

Samples and interview

The narration of the team formation, working strategies, achievements and lessons from this international research collaboration was obtained through an in-depth interview conducted among members of ATReG. The members were in nine different countries namely, Australia, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, United Kingdom and Tanzania. All members of the group except for one who declined interview were purposively sampled in this research. The interviews were conducted virtually either via Zoom video conferencing applications or scheduled telephone calls, depending on member’s preference, and at a convenient time for the respective respondents. With the consent of the respondent, the interviews were audio-recorded, and notes taken by a note taker. In total, 13 interviews were conducted; each interview lasted about an hour thirty minutes to two hours.

Data analysis

A thematic analysis of the data was conducted in six phases as suggested by Braun & Clarke (2006). Phase 1 was the familiarization with the data where the recording was listened to by two independent researchers and thereafter, the interviews were transcribed verbatim using the Otter.ai transcription application and complemented manually using both the tape recordings and the notes taken during the interview. The transcripts were read thoroughly and comprehensively to generate initial codes (phase 2) and subsequently, themes and subthemes were generated using the inductive and deductive approaches (phase 3) (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). The sub-themes were reviewed for accurate representation and checked to ensure they fit the main themes and objective of the study. Those that did not fit, were eventually discarded before the final analysis (phase 4). The final themes and sub-themes were labelled, and the data analysed using Excel (phase 5). Finally, the results were produced, and the reports presented using the various themes and important quotes (phase 6).

Findings

Characteristics of the research team

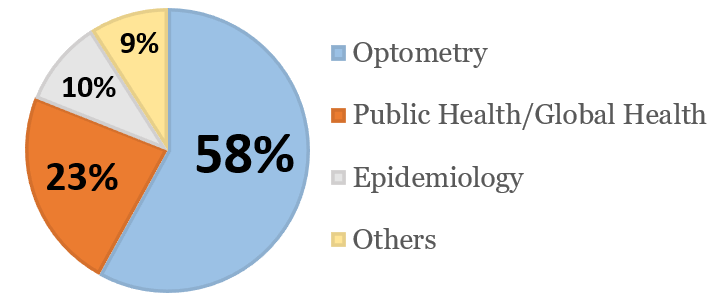

In total, 13 interviews were conducted, one member declined to participate for lack of time, resulting in a response rate of 92.9%. Each interview lasted about an hour thirty minutes to two hours. The respondents were aged between 39 and 62 years, mostly men (10, 76.9%), majority were from English speaking countries in SSA (11, 84.6%), had postgraduate qualifications in various fields (figure 1) and two were Professors, one in health-related specialty (Optometry) and the other in computer science. Analysis of the interview transcripts revealed three main themes, which are shown in Table 1: (1) membership/group composition and roles (2) organisational structure and coordination/strategies and (3) success stories, achievements and challenges related to international research collaborations on Africa during the pandemic.

Thematic responses

Table 1 shows the different themes and sub-themes that emerged from the interview. At the time of this study, the group had published 10 peer reviewed jounal articles in respected public health outlets. The group also published two policy articles in the Australian and African editions of the Conversation. Also, ATReG made presentations at two separate international conferences. The group also published translated research in three newspaper articles, one in Ghana and two in Nigeria and successfully obtained a highly competitive research grant award from the Nigerian Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFUND). According to the respondents, the social factors responsible for the research successes of ATReG included strong social relationships and ties between members, mutual tolerance and mutual respect, having a team ethos, a strong central coordinator, and strong trust in each other’s ability.

Figure 1. Areas of specializations of the research group members. The categories included computer science, human nutrition, supply chain management, psychiatry.

Table 1. Analysis of responses of group members by the themes and sub-themes that emerged from the interview.

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Results | Participants’ Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composition/ organization/roles |

Membership What constituted membership? Organization structure/coordination Roles in the group |

Majority of the members joined the group by invitation from someone known to them in the group. This was closely followed by those who were contacted by a member because of their research background. For the majority, being an African researcher was what constituted membership, but others said there was no criteria for being a member because people were either invited by their friends or recommended by someone else. All the members agreed there was no formal structure but there was some form of informal structure. A member of the group mostly coordinated the activities of the group with some assistance from others. Majority said there were no specific roles but that they were assigned roles based on needs. There were a few specific roles like those of statistical analysis. |

So there was a need to expand and reach out to other African countries, I was invited by my teacher It was my head of department that recommended my name for that team But the initial idea was to try and drive research from an African perspective Research for Africa, for Africans, in Africa and by Africa Constituents of very high intellectual people at different level The person who initiated this group, has done a tremendous job in coordinating and leading Yes there are no specific roles, but depending, particularly statistical aspect of it, and the interpretation of those statistical responses It’s based on your strengths, because we are always asked what can you do |

| Success stories/ achievements |

Achievements Reasons for the achievements |

Most members considered the biggest achievement of the group to be the number of publications within a short period and also the successful collaboration in the group. A few others considered the group biggest achievement as the grant received while other members indicated that career progression and promotion as a result of the activities of the group was the biggest achievement When asked about the factors responsible for the achievements in the group, the majority said it was because of the high level of commitment from the members while a significant number said the simplicity of the members was the reason for the achievement. This was followed by those who said the manner of communication, which is perceived to be good, prompt and respectful was the reason for the achievement that was recorded in the group. |

Publication that we’ve had and actually opening up the way to interregional, intercontinental inter-country research I think, is that ability to bring people from different backgrounds, people from different categories. Being able to put in a proposal that attracted some research funds. Commitment, the people know what they are about, focus, and they are ready to work. Their simplicity, their hard work, they are focused on what we were to achieve There’s good communication |

| Challenges and recommendations |

Challenges Recommendations |

Lack of funding was the biggest challenge mentioned by the majority of the members as a draw back for the group. A few other members said the lack of a formal organizational structure and the meeting times, which was usually Saturdays, was a challenge because it was not convenient but they had to attend due to their commitment to the group while others saw the focus of the group on one research area without diversification as a draw back. Most members recommended a formal structure should be put in place moving forward to help with the coordination of the activities. Identifying a funding source was also mentioned by most members as what they would recommend moving forward or what they would do differently if they have to set up a group like this in the future. |

We have challenges in terms of funding, I think going forward, it’s important that we look at, you know, the support of institutions. I think what I see is that we are limited to certain types of research, for now we have not been diversified as that, but we also need to be diversified. There should be some sort of formal structure, even if it’s not as formal as is done in other groups, there has to be structures, Structure going forward, Yeah I would want to have funding before I start, we need to identify source of income for publications |

Discussion

The working principles and several achievements of the group were identified and reported under three important themes. The themes, which included, group composition and working strategies, successes and achievements of the group, the group’s challenges and future recommendations moving forward, are discussed below

Group composition and working strategies

Group members are from different SSA countries and were invited to join the group either by someone known to them who was already in the group or through referral from a member of their institution who was not part of the group, because of their research background. Members included researchers, clinicians or programme officers and spoke mainly English and French, which connotes the concept of collaboration that describes the involvement of people from different contexts and experiences or perspectives coming together for a purpose (Nyström et al., 2018).

Inter-individual collaborative research is becoming popular amongst scholars with advancement in information and communication technology and globalisation in research agenda (Carayol & Roux, 2007). Inter-individual collaborative research is also growing to increase research productivity and attract higher numbers of citations (Katz & Martin, 1997). Coordination is often needed in collaborative research to ensure smooth running, commitment, and performance by the diverse partners (Bansal et al., 2019). Different collaborating groups adopt different approaches such as having a formal structure or an informal structure like the type presented in this study. ATReG was set up without a formal organisational structure but has effectively functioned with successes through an informal coordination by one of the conveners of the group. The coordination mechanisms used were frequent online meetings, WhatsApp messaging, emails, and phone calls. On the contrary, Nyström et al. (2018) found that projects were more successful if they use more coordination mechanisms compared to those that use fewer coordinating mechanisms.

Depending on the approach chosen in research collaboration, partners can be involved from the stage of the design, data collection, analysis, report, or manuscript writing to the final dissemination. Roles were mostly assigned to members based their area of strength and voluntariness. There are no permanent roles in the collaborating team except for a couple of scholars with aptitude for and skills in statistical analysis. There was however active and collective participation by members of the group from conceptualization of topics, research design, to the design of data collection instruments, actual data collection, analysis and reporting through a rigorous review process during their regular meetings. This approach has also been successful in other international collaborations involving researchers from diverse cultures who were at different career stages in North American, European, Middle Eastern, and East Asian universities (Dusdal & Powell, 2021). Numerous factors influence collaborative research, and they are usually driven by funding organizations. The group was established on the premise of wanting to promote collaborative research in Africa by Africans and this was captured in a respondent’s statement; “But the initial idea was to try and drive research from an African perspective”, “It is a Research, for Africa, in Africa and by Africans”.

Success stories/ achievements

Although the initial objective of the group was to conduct research with the focus on COVID-19, this later expanded to other research areas. The group achieved successes by the numerous peer reviewed publications, including COVID-19 myths in Sub Saharan Africa (Osuagwu et al., 2021; Ovenseri-Ogbomo et al., 2020) which was part of a World Health Organization sponsored series, Risk perception of COVID-19 among SSA (Abu et al., 2021), and compliance to public health practices during the pandemic (Nwaeze et al., 2021) within the eighteen months period; and successful award of a competitive national grant from the Federal Government of Nigeria. These were considered as the greatest achievements by many in the group because both the grant and the publications have accelerated their career progression and academic promotion to higher levels. It has also elevated their research, academic and professional careers profiles above those of their peers. Some members reported that they got promoted to Associate Professorship and others mentioned that they were assigned higher responsibilities, and became more visible in their institutions and other professional groups as a result of the publications and conference presentations. The social relationships formed, and networking opportunities were also viewed as more valuable achievements of the collaborative team than the publications and grants by some members, considering that the group was formed during the COVID-19 lockdown, a period of increased isolation and loneliness (Wu, 2020).

As documented by other research collaboration teams, successful international research collaboration is the result of synergy and commitment among diverse partners, where every partner is willing to work and contribute positively to the group, in addition to the effective coordination of the group’s activities (Cummings & Kiesler, 2005). The most reported motivation in this collaborative research were the groups’ diverse competencies, level of commitment, simplicity, respect for one another and hard work. Good communication is an important concern raised in inter-cultural/inter-country and inter-disciplinary collaborative research, and in this study, participants appreciated the good communication and high level of respect. They considered these to be motivating factors for their active involvement and high performance.

Challenges and recommendations

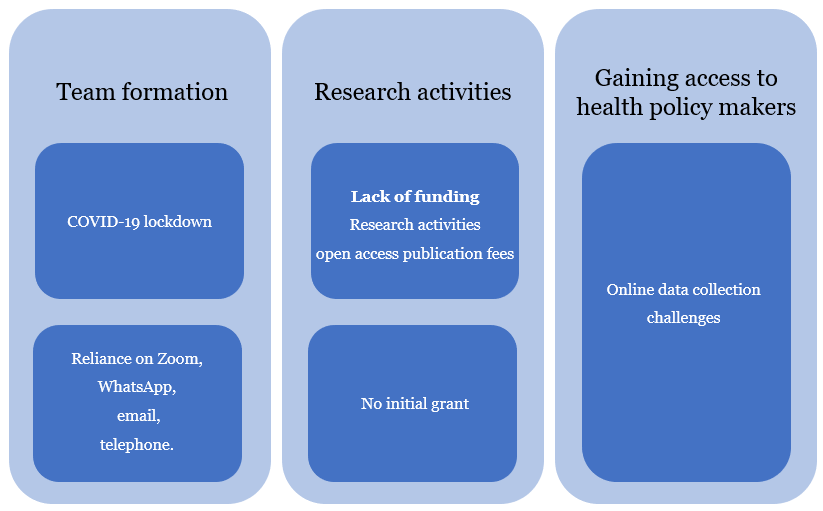

Figure 2 presents a summary of the challenges of ATreG. Although the research collaboration was among Africans for African health and COVID-19 policymakers, there were some challenges posed by the differences in time zones since some members of ATReG were residing outside of Africa at the time of the collaboration, which made virtual meetings, the most convenient option. Even though the meeting times were not convenient for some members, they made regular sacrifices to attend the meetings due to the commitment. With diverse membership and multiple activities, it was expected that bottlenecks and challenges would be encountered. Respondents felt research activities were tasking and meeting deadlines were overwhelming. The process of designing and writing manuscripts and grant proposals were perceived as time consuming and challenging as was also noted in another study (Martin, 2010).

Figure 2. Challenges to team formation and research activities.

Figure 2. Challenges to team formation and research activities.

Some other challenges that were reported by members which are peculiar to most collaborating groups were financial constrains in funding research activities, and a lack of formal structure. There were also issues with payment of open access publication fees which the respondents thought could be overcome by identifying a funding source subsequently for future activities and sustainability of the group. Although the group has managed well without a formal structure or source of funding, respondents felt there is a need for a formal coordinating structure believing it will help achieve better productivity and ease up the workload on few individuals especially as the scope and mandate of the group is expanding.

Conclusions

This study revealed that international inter-disciplinary health research collaboration among African researchers during the pandemic could result in great achievements in publications and contribute to career progression and academic promotion for its members, even though they never met in person. There were challenges with data collection, which were mostly done online, as well as the intermittent financial challenges in funding research activities and publications. Collaborative research is a model for researchers and a critical way to foster and maintain global innovation and research successes, particularly around public health. However, there is the paramount need to have a central coordination to drive projects, frequently pull all team members together while ensuring that team members are working collectively and cohesively as a team through intensive and effective communications and coordination with team members online.

Furthermore, there were lessons that emerged from the complexity of the context of the collaboration. These include the transnational, transcultural nature, and subsequent reliance on online tools such as Zoom and WhatsApp for communications, over the period, and the collaboration of researchers at different career stages (senior scholars, mid-career researchers (MCR) and early career researchers (ECR)) and in different part of the globe with researchers based in African institutions who speak French and/or English language with no conflict, grievance or group breakdown.

The collaboration also involved knowledge exchange between researcher’s resident in Africa and those in the diaspora through presentations and discussions during meetings. Learning from the successes and challenges in such a large cross-cultural collaborative team can be replicated any researcher in any discipline at any level of career and experience. We reported on the need to develop swift trust of team members even when one hardly knows the other and the fact that all team members need to take on a mature, tolerant, and respectful stance towards others, their opinions, and perspectives.

Acknowledgement: None

Funding information: The authors received no funding for this study

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References

Abu, E. K., Oloruntoba, R., Osuagwu, U. L., Bhattarai, D., Miner, C. A., Goson, P. C., . . . Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G. O. (2021). Risk perception of COVID-19 among sub-Sahara Africans: a web-based comparative survey of local and diaspora residents. BMC public health, 21(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11600-3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arslan, A., Golgeci, I., Khan, Z., Al-Tabbaa, O., & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. (2020). Adaptive learning in cross-sector collaboration during global emergency: conceptual insights in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Multinational Business Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/mbr-07-2020-0153 [Google Scholar]

Bagshaw, D., Lepp, M., & Zorn, C. R. (2007). International research collaboration: Building teams and managing conflicts. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 24(4), 433-446. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.183 [Google Scholar]

Bansal, S., Mahendiratta, S., Kumar, S., Sarma, P., Prakash, A., & Medhi, B. (2019). Collaborative research in modern era: Need and challenges. Indian journal of pharmacology, 51(3), 137. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijp.ijp_394_19 PubMed [Google Scholar]

Berger, C., Doherty, P., Rudol, P., & Wzorek, M. (2021). Hastily formed knowledge networks and distributed situation awareness for collaborative robotics. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.14078. [Google Scholar]

Bozeman, B., & Boardman, C. (2014). Assessing research collaboration studies: A framework for Analysis. In Research collaboration and team science: A state-of-the-art review and agenda (pp. 57): Springer. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Carayol, N., & Roux, P. (2007). The strategic formation of inter-individual collaboration networks. Evidence from co-invention patterns. Annales d'Economie et de Statistique, 275-301. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Chen, K., Zhang, Y., & Fu, X. (2019). International research collaboration: An emerging domain of innovation studies? Research Policy, 48(1), 149-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.005 [Google Scholar]

Cheng, X., Fu, S., Sun, J., Han, Y., Shen, J., & Zarifis, A. (2016). Investigating individual trust in semi-virtual collaboration of multicultural and unicultural teams. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 267-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.093 [Google Scholar]

Cummings, J. N., & Kiesler, S. (2005). Collaborative research across disciplinary and organizational boundaries. Social studies of science, 35(5), 703-722. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312705055535 [ISI] [Google Scholar]

D’ippolito, B., & Rüling, C.-C. (2019). Research collaboration in Large Scale Research Infrastructures: Collaboration types and policy implications. Research Policy, 48(5), 1282-1296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.01.011 [Google Scholar]

Dusdal, J., & Powell, J. J. (2021). Benefits, motivations, and challenges of international collaborative research: A sociology of science case study. Science and Public Policy, 48(2), 235-245. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scab010 [Google Scholar]

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of advanced nursing, 62(1), 107-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [PubMed] [ISI] [Google Scholar]

Ernberg, I. (2019). Education aimed at increasing international collaboration and decreasing inequalities. Molecular Oncology, 13(3), 648-652. https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.12460 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fry, C. V., Cai, X., Zhang, Y., & Wagner, C. S. (2020). Consolidation in a crisis: Patterns of international collaboration in early COVID-19 research. PloS one, 15(7), e0236307. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fu, X., & Li, J. (2016). Collaboration with foreign universities for innovation: evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. International Journal of Technology Management, 70(2-3), 193-217. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtm.2016.075162 [Google Scholar]

Garg, K. C., & Padhi, P. (2001). A study of collaboration in laser science and technology. Scientometrics, 51(2), 415-427. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1012709919544 [Google Scholar]

Glänzel, W. (2001). National characteristics in international scientific co-authorship relations. Scientometrics, 51(1), 69-115. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010512628145 [ISI] [Google Scholar]

Hedges, J. R., Soliman, K. F., Southerland, W. M., D’Amour, G., Fernández-Repollet, E., Khan, S. A., . . . Yates, C. C. (2021). Strengthening and Sustaining Inter-Institutional Research Collaborations and Partnerships. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(5), 2727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052727 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Iglič, H., Doreian, P., Kronegger, L., & Ferligoj, A. (2017). With whom do researchers collaborate and why? Scientometrics, 112(1), 153-174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2386-y [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jit, M., Ananthakrishnan, A., McKee, M., Wouters, O. J., Beutels, P., & Teerawattananon, Y. (2021). Multi-country collaboration in responding to global infectious disease threats: lessons for Europe from the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Regional Health-Europe, 9, 100221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Katz, J. S., & Martin, B. R. (1997). What is research collaboration? Research Policy, 26(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-7333(96)00917-1 [ISI] [Google Scholar]

Kwiek, M. (2021). What large-scale publication and citation data tell us about international research collaboration in Europe: Changing national patterns in global contexts. Studies in Higher Education, 46(12), 2629-2649. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1749254 Google Scholar

Martin, S. (2010). Co-production of social research: strategies for engaged scholarship. Public Money & Management, 30(4), 211-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2010.492180 [ISI] [Google Scholar]

Mascarenhas, C., Ferreira, J. J., & Marques, C. (2018). University–industry cooperation: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Science and Public Policy, 45(5), 708-718. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scy003 [Google Scholar]

Milman, N. B. (2021). Cultivating Swift Trust in Virtual Teams in Online Courses. Distance Learning, 18(2), 45-47. [Google Scholar]

Nwaeze, O., Langsi, R., Osuagwu, U. L., Oloruntoba, R., Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G. O., Abu, E. K., . . . Goson, P. C. (2021). Factors affecting willingness to comply with public health measures during the pandemic among sub-Sahara Africans. African Health Sciences, 21(4), 1629-1639, https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v21i4.17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nyström, M. E., Karltun, J., Keller, C., & Andersson Gäre, B. (2018). Collaborative and partnership research for improvement of health and social services: researcher’s experiences from 20 projects. Health research policy and systems, 16(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0322-0 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Osuagwu, U. L., Miner, C. A., Bhattarai, D., Mashige, K. P., Oloruntoba, R., Abu, E. K., . . . Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G. O. (2021). Misinformation about COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Health security, 19(1), 44-56. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2020.0202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G. O., Ishaya, T., Osuagwu, U. L., Abu, E. K., Nwaeze, O., Oloruntoba, R., . . . Langsi, R. (2020). Factors associated with the myth about 5G network during COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Global Health Reports. https://doi.org/10.29392/001c.17606 [Google Scholar]

Plotnikova, T., & Rake, B. (2014). Collaboration in pharmaceutical research: exploration of country-level determinants. Scientometrics, 98(2), 1173-1202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-1182-6 [Google Scholar]

Rubio Doris McGartland, Schoenbaum Ellie E, Lee Linda S, Schteingart David E, Marantz Paul R, Anderson Karl E, Platt Lauren Dewey, Baez Adriana, Esposito Karin (2010). Defining translational research: implications for training. Acad Med, 85(3), 470–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ccd618 [PubMed] [ISI] [Google Scholar]

Sharma, S., & Thomas, V. (2008). Inter-country R&D efficiency analysis: An application of data envelopment analysis. Scientometrics, 76(3), 483-501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-007-1896-4 [Google Scholar]

Taras, V., Caprar, D. V., Rottig, D., Sarala, R. M., Zakaria, N., Zhao, F., . . . Minor, M. S. (2013). A global classroom? Evaluating the effectiveness of global virtual collaboration as a teaching tool in management education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 12(3), 414-435, https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0195 [ISI] [Google Scholar]

Vervoort, D., Ma, X., & Luc, J. G. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic: a time for collaboration and a unified global health front. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 33(1), mzaa065. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa065 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wagner, C. S. (2009). The new invisible college: Science for development: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

Wang, C., Rodan, S., Fruin, M., & Xu, X. (2014). Knowledge networks, collaboration networks, and exploratory innovation. Academy of Management Journal, 57(2), 484-514. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0917 [Google Scholar]

Wu, B. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: a global challenge. Global health research and policy, 5(1), 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-020-00154-3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yu, X., Shen, Y., & Khazanchi, D. (2021). Swift Trust and Sensemaking in Fast Response Virtual Teams. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2021.1978114 [Google Scholar]

Zakaria, N., & Yusof, S. A. M. (2020). Crossing cultural boundaries using the internet: Toward building a model of swift trust formation in global virtual teams. Journal of International Management, 26(1), 100654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2018.10.004 [Google Scholar]