-

Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199-1207. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Xiao Y, Torok ME. Taking the right measures to control COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):523-524. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(3):105924. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

World Health Organization (WHO). Weekly epidemiological update - 23 February 2021. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update—23-february-2021

[Google Scholar]

-

World Health Organization (WHO). Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Geneva: WHO; 2020. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf

[Google Scholar]

-

Chang L, Yan Y, Wang L. Coronavirus disease 2019: coronaviruses and blood safety. Transfus Med Rev. 2020;34(2):75-80. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Lupia T, Scabini S, Mornese Pinna S, Di Perri G, De Rosa FG, Corcione S. 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak: a new challenge. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;21:22-27. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-1720. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): latest updates on the COVID-19 crisis from Africa CDC 2020. Accessed February 24, 2021. https://africacdc.org/covid-19

[Google Scholar]

-

Ogolodom MP, Mbaba AN, Alazigha N, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and fears of healthcare workers towards the corona virus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in South-South, Nigeria. Health Sci J. 2020;Sp Iss 1:002.

[Google Scholar]

-

Di Gennaro F, Pizzol D, Marotta C, et al. Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) current status and future perspectives: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2690. [Crossref]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Law S, Leung AW, Xu C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): from causes to preventions in Hong Kong. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:156-163. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Hamadani JD, Hasan MI, Baldi AJ, et al. Immediate impact of stay-at-home orders to control COVID-19 transmission on socioeconomic conditions, food insecurity, mental health, and intimate partner violence in Bangladeshi women and their families: an interrupted time series. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(11):e1380-e1389. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Bhagavathula AS, Aldhaleei WA, Rahmani J, Mahabadi MA, Bandari DK. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among health care workers: cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e19160. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1499-1500. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Blendon RJ, Benson JM, DesRoches CM, Raleigh E, Taylor-Clark K. The public's response to severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto and the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(7):925-931. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Lau JT, Yang X, Tsui H, Kim JH. Monitoring community responses to the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: from day 10 to day 62. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(11):864-870. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Ajisegiri W, Odusanya O, Joshi R. COVID-19 outbreak situation in Nigeria and the need for effective engagement of community health workers for epidemic response. Glob Biosecur. 2020;1(4).

[Google Scholar]

-

Deaton AS, Tortora R. People in sub-Saharan Africa rate their health and health care among the lowest in the world. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(3):519-527. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Ekpenyong B, Obinwanne CJ, Ovenseri-Ogbomo G, et al. Assessment of knowledge, practice and guidelines towards the novel COVID-19 among eye care practitioners in Nigeria–a survey-based study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5141. [Crossref]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Matsuishi K, Kawazoe A, Imai H, et al. Psychological impact of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 on general hospital workers in Kobe. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;66(4):353-360. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Li Y, Wang H, Jin XR, et al. Experiences and challenges in the health protection of medical teams in the Chinese Ebola treatment center, Liberia: a qualitative study. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):92. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Orentlicher D. The physician's duty to treat during pandemics. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(11):1459-1461. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Smith RD. Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(12):3113-3123. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Janjua NZ, Razaq M, Chandir S, Rozi S, Mahmood B. Poor knowledge–predictor of nonadherence to universal precautions for blood borne pathogens at first level care facilities in Pakistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:81. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Ilesanmi O, Alele FO. Knowledge, attitude and perception of Ebola virus disease among secondary school students in Ondo State, Nigeria , October, 2014. PLoS Curr. 2016;8:ecurrents.outbreaks.c04b88cd5cd03cccb99e125657eecd76.

[Google Scholar]

-

Zhong NS, Wong GW. Epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): adults and children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;(4)5:270-274. [Crossref]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Abuya T, Austrian K, Isaac A, et al. COVID-19-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices in urban slums in Nairobi, Kenya. Population Council. Published 2020. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://www.popcouncil.org/research/covid-19-related-knowledge-attitudes-and-practices-in-urban-slums-in-nairob

[Google Scholar]

-

Abdelhafiz AS, Mohammed Z, Ibrahim ME, et al. Knowledge, perceptions, and attitude of Egyptians towards the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). J Community Health. 2020;45(5):881-890. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Abir T, Kalimullah NA, Osuagwu UL, et al. Factors associated with the perception of risk and knowledge of contracting the SARS-Cov-2 among adults in Bangladesh: analysis of online surveys. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5252. [Crossref]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Zhong BL, Luo W, Li HM, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1745-1752. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Reuben RC, Danladi MMA, Saleh DA, Ejembi PE. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: an epidemiological survey in North-Central Nigeria. J Community Health. July 7, 2020. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00881-1

[Google Scholar]

-

Parikh PA, Shah BV, Phatak AG, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: knowledge and perceptions of the public and healthcare professionals. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e8144. [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang M, Zhou M, Tang F, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Henan, China. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(2):183-187. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Nkansah C, Serwaa D, Adarkwah LA, et al. Novel coronavirus disease 2019: knowledge, practice and preparedness: a survey of healthcare workers in the Offinso-North District, Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(suppl 2):79. [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Olum R, Chekwech G, Wekha G, Nassozi DR, Bongomin F. Coronavirus disease-2019: knowledge, attitude, and practices of health care workers at Makerere University teaching hospitals, Uganda. Front Public Health. 2020;8:181. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. COVID-19 situation update for the WHO Africa Region, 12 May 2020. Published May 13, 2020. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332078/SITREP_COVID-19_WHOAFRO_20200513-eng.pdf

[Google Scholar]

-

World Health Organization (WHO). Survey Tool and Guidance: Behavioural Insights on COVID-19. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Accessed February 24, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/333549

[Google Scholar]

-

Li ZH, Zhang XR, Zhong WF, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to Coronavirus disease 2019 during the outbreak among workers in China: a large cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(9):e0008584. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MS, et al. Risk of COVID-19 among frontline healthcare workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(9):e475-e483. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Wang J, Zhou M, Liu F. Reasons for healthcare workers becoming infected with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(1):100-101. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Moro M, Vigezzi GP, Capraro M, et al. 2019-novel coronavirus survey: knowledge and attitudes of hospital staff of a large Italian teaching hospital. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(suppl 3):29-34. [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Papagiannis D, Malli F, Raptis DG, et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) of health care professionals in Greece before the outbreak period. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):4925. [Crossref]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Puspitasari IM, Yusuf L, Sinuraya RK, Abdulah R, Koyama H. Knowledge, attitude, and practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:727-733. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Hu Z, Chen B. The status of psychological issues among frontline health workers confronting the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2020;8:265. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Shaukat N, Ali DM, Razzak J. Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a scoping review. Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13(1):40. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1924-1932. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Nicholas T, Mandaah FV, Esemu SN, et al. COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes and practices in a conflict affected area of the South West Region of Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(2):34. [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Usman IM, Ssempijja F, Ssebuufu R, et al. Community drivers affecting adherence to WHO guidelines against covid-19 amongst rural Ugandan market vendors. Front Public Health. 2020;8:340. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Serwaa D, Lamptey E, Appiah AB, Senkyire EK, Ameyaw JK. Knowledge, risk perception and preparedness towards coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) outbreak among Ghanaians: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(2):44. [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Ejeh FE, Saidu AS, Owoicho S, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice among healthcare workers towards COVID-19 outbreak in Nigeria. Heliyon. 2020;6(11):e05557. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Alobuia WM, Dalva-Baird NP, Forrester JD, Bendavid E, Bhattacharya J, Kebebew E. Racial disparities in knowledge, attitudes and practices related to COVID-19 in the USA. J Public Health (Oxf). 2020;42(3):470-478. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Galasso V, Pons V, Profeta P, Becher M, Brouard S, Foucault M. Gender differences in COVID-19 related attitudes and behavior: evidence from a panel survey in eight OECD countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(44):27285-27291. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Peng Y, Pei C, Zheng Y, et al. A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitude and practice associated with COVID-19 among undergraduate students in China. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1292. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Bwire GM. Coronavirus: Why men are more vulnerable to Covid-19 than women? SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2:874-876. [Crossref]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Blustein DL, Duffy R, Ferreira JA, Cohen-Scali V, Cinamon RG, Allan BA. Unemployment in the time of COVID-19: a research agenda. J Vocat Behav. 2020;119:103436. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Khosravi M. Perceived risk of COVID-19 pandemic: the role of public worry and trust. Electron J Gen Med. 2020;17(4):em203. [Crossref]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Dryhurst S, Schneider CR, Kerr J, et al. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J Risk Res. 2020;23(7-8):994-1006. [Crossref]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Abdel Wahed WY, Hefzy EM, Ahmed MI, Hamed NS. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and perception of health care workers regarding COVID-19, a cross-sectional study from Egypt. J Community Health. 2020;45(6):1242-1251. [Crossref], [Medline]

, [Google Scholar]

-

Hjort J, Poulsen J. The arrival of fast internet and employment in Africa. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109(3):1032-1079. [Crossref]

, [Google Scholar]

Version of Record (VoR)

Ekpenyong, B., Osuagwu, U. L., Miner, C. A., Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G. O., Abu, E. K., Goson, P. C., … Agho, K. E. (2021). Knowledge, attitude, and perception of COVID-19 among healthcare and non-healthcare workers in Sub-Saharan Africa : a web-based survey. Health Security, 19(4), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2020.0208

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perception of COVID-19 Among Health Care and Non-Health Care Workers in Sub-Sahara Africa:

A Web-based Survey

Running title: Health and Non-health workers’ COVID-19 related KAP

Abstract

Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic and associated high mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), there is panic amongst healthcare workers (HCWs) because of the higher risk of being infected. This study compared knowledge, attitude and perception (KAP) towards COVID-19 between HCWs and non- healthcare care workers (NHCWs) and examined common associated factors. A web-based cross-sectional study on 1871 participants (HCWs=430, NHCWs=1441) was conducted over a period when lockdown measures were in place in the four SSA regions. Data were obtained using a validated self-administered questionnaire disseminated through an online survey platform. KAP mean scores were calculated and summarized using t-test for NHCWs and HCWs. Multivariate linear regression analyses was conducted to assess the unadjusted (B) and adjusted coefficients (β) at 95% confidence interval (CI). The mean KAP scores were slightly higher among HCWs than non-HCWs, but not statistically significant. Worried about COVID-19 was the only common factor associated with KAP between the two groups. Knowledge of COVID-19 was associated with attitude and perception between the two groups. Other significant factors associated with KAP were: the SSA region, age 29-38 years (β= 0.32, 95%CI: 0.04, 0.60 for knowledge in NHCWs), education, (β = -0.43, 95%CI -0.81, -0.04 and β= -0.95, 95%CI -1.69, -0.22, for knowledge in NHCWs and HCWs, respectively), practice of self-isolation (β=0.71, 95%CI 0.41, 1.02 for attitude in NHCWs and HCWs (β= 0.97, 95%CI 0.45, 1.49), and home quarantine due to COVID-19, in both groups. Policymakers and health care providers should consider these factors when targeting interventions during COVID-19 and other future pandemics.

Keywords: frontline workers, COVID-19, pandemic, lockdown, knowledge, risk perception.

Introduction

The global population is threatened by the raging pandemic caused by novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which started in Hubei Province of the People's Republic of China in 2019.1-4 The disease spreads among humans through respiratory droplets of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients,5 with the classic respiratory symptoms of fever, cough and fatigue.6-11 As at 4th August 2020, the Africa Centre of Disease Control (CDC), confirmed over 17.9m cases of COVID-19 and over 687,011 deaths across the African regions, with Southern Africa reporting the highest burden of the infection and Central Africa reporting the least.12 Like most developed countries, many countries in SSA are now in the second and third epidemic phases,12 suggesting the need to strengthen the public health control measures put in place by SSA government to contain the spread of the outbreak.

To mitigate the impact of the disease, the respective SSA governments implemented various recommended public health strategies such as bans on public gatherings, travel bans, social distancing, use of facemasks and others.2, 13-15 However, compliance with these measures were variable, largely dictated by economic and other factors.16 With no antiviral treatment or vaccine recommended explicitly for COVID-19 at the time,17, 18 management of severe hospitalized cases consisted of ensuring appropriate infection control and supportive care.14 A confused comprehension of an emerging disease combined with inadequate expert knowledge can lead to fear and chaos, further aggravating the pandemic.19 Past experience with outbreaks such as SARS and Ebola showed that misconceptions and excessive panic in the public led to the resistance to comply with suggested preventive measures and contributed to the rapid spread of the diseases.20, 21 These experiences underscore the vital role of engaging with both healthcare and non-healthcare professionals and the importance of monitoring their knowledge and compliance with the pandemic control measures.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the people’s perception of their health is rated among the lowest in the world. This may be connected with the low prioritization of health and health care by the respective governments in the four regions.22 According to WHO (2012), improving health care services delivery and disease control in Africa goes beyond increased financing and policy but also encompasses community perceptions and perspectives. As active players in the pandemic response, the healthcare worker is extremely strained.1, 23-26 Since COVID-19 is caused by a novel coronavirus, there is a dearth of accurate information available to healthcare workers and non-healthcare alike. Level of knowledge has a direct effect on an individual’s perception of susceptibility to disease and compliance with preventive protocols that could result in delayed treatment and a rapid spread of infection.27-29 Hence, it is crucial to understand people's attitude, their perceived risk of contracting the disease and compliance towards to mitigation practices to effectively communicate and frame key messages in response to the emerging disease.30

Country-specific studies on knowledge, attitude and perception (KAP) of COVID-19 control measures among the general population31-35 and among HCWs17, 36-39 have been reported within and outside Africa. However, no study has compared the KAP of COVID-19 among HCWs and NHCWs in SSA. Understanding related factors affecting and influencing people's decision to undertake precautionary behaviour may help decision-makers respond appropriately to promote individual or community health in a pandemic situation. Comparing knowledge, attitude and risk perception between HCWs and NHCWs will also help to tailor health education messages to each specific group rather than a generic message that does not consider the difference between the two groups of people. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the differences in KAP scores as well as compliance with COVID-19 public health control measures, between HCWs and NHCWs in SSA, and to determine the common associated factors.

Materials and methods

From 18th April to 16th May 2020 corresponding to the lockdown period in the four SSA regions, this web-based cross-sectional survey was conducted among respondents from Cameroon (Central Africa), Ghana, Nigeria (Western Africa), Kenya, Tanzania (East Africa) and South Africa (Southern Africa). All of these countries have reported cases of COVID-19 in the recent pandemic, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The survey was only available in English language and an e-link of the questionnaire was posted on social media platforms (Facebook and WhatsApp) which were commonly used by the locals in the participating countries, and was sent via emails by the researchers to broaden the scope of the survey. Participants in the survey received no incentives.

Sample size determination

The survey assumed a proportion of 50% because there was no previous studies on from SSA that has examined factors associated with 2019-nCoV in HCW and NHCWs, with 95% confidence and 2.5% margin of error. Using an online calculator, we assumed a sample size of approximately 1921, including 20% non-response rate. However, 1871 (97.4%) participants responded to the desired questions.

Consent and ethical consideration

The participants responded with a 'yes' or 'no' to a question designed to obtain voluntary online consent to express their willingness to attend the study via survey monkey. Human Research Ethics Committee of the Cross-River State Ministry of Health in Nigeria (Human ethics approval number: CRSMOH/HRP/HREC/2020/117) approved this study. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. To participate in this study, respondents had to be 18 years and above. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Questionnaire

The survey tool for the COVID-19 knowledge questionnaire was developed based on the guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO) for clinical and community management of COVID-1940. The questionnaire was adapted with some modifications to suit this study’s objective namely to explore the knowledge of healthcare and non-healthcare workers about the nature and origin of COVID-19 and their attitude and perception towards the mitigation strategies to control the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Prior to the launching of the survey, a pilot study was conducted to ensure clarity and understanding and to determine the duration for completing the questionnaire. Participants (n=10) who took part in the pilot were not part of the research team and did not participate in the final survey as well. This was a self-administered 58-item questionnaire divided into four sections (A) demographic characteristics (B) knowledge (C) attitude and (D) risk perception. Demographic variables included age, gender, marital status, education, employment, occupation, the number living in the household, and religion.

Dependent variables

The three dependent variables were knowledge, attitude towards COVID-19 and risk perception for contracting the disease, which were taken as continuous variables. Twelve items on the questionnaire assessed the respondent's knowledge of COVID- 19, most of which required a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response. Each question used a binary scale. The score for each ranged from ‘yes’ (score ‘1’) to ‘no’ (score ‘0’). The knowledge score ranged from 0–12 points and these items have been shown to have an acceptable internal consistency41. The survey tool for the COVID-19 knowledge questionnaire was developed based on the guidelines from the World Health Organization42 for clinical and community management of COVID-19. There were 15 items in the survey (each used a Likert scale with five levels) that assessed perception of risk for contracting COVID-19. The scores for each item ranged from 0 (lowest) to 4 (highest). The risk perception score ranged from 0–60 points and the Cronbach's alpha coefficients of the items were 0.74 indicating satisfactory internal consistency. The COVID-19 attitude items included “whether they have gone to any crowded place such as religious events?” “if they wore a mask when leaving home?”, and “if in recent days, they have been washing their hands with soap for at least 20 seconds each time”. Each question used a Likert scale with five levels with scores for each item ranging from 0 (lowest) to 4 (highest). The total scores ranged from 0-24 points, and the Cronbach's alpha coefficient of attitude items was an average of 0.73, indicating acceptable internal consistency.

Independent variables

The independent variables were as follows: The demographic characteristics included age, country of origin, country of residence, sex, religion, educational, marital and occupational status, number of people living together in the household. Attitude towards COVID-19 included compliance to mitigation practices to minimize the spread of the virus such as, domestic self-isolation and quarantine measures. The risk perception variables included questions on, how they felt about the quarantine, whether participants think they were at risk of becoming infected, at risk of dying from the infection, if they were worried about contracting COVID-19, and participants' feeling towards self-isolation (Table 1). Questions on knowledge and attitude towards COVID-19 were included when each variable was not the dependent variable in the analysis.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Knowledge, Attitude, and Risk Perception Scores Among HCWs and Non-HCWs in Sub-Saharan Africa

| Knowledge | Attitude | Perception | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Non-HCW n |

HCW n |

Non-HCW Mean (SD) |

HCW Mean (SD) |

Non-HCW Mean (SD) |

HCW Mean (SD) |

Non-HCW Mean (SD) |

HCW Mean (SD) |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Region | 1441 | 430 | 7.20 (2.18) |

7.16 (2.25) |

13.64 (5.25) |

13.80 (5.14) |

20.56 (7.81) |

21.27 (7.92) |

| West Africa | 788 | 280 | 7.14 (2.27) |

7.21 (2.13) |

13.16 (5.24) |

13.49 (5.00) |

20.36 (7.90) |

21.59 (7.68) |

| East Africa | 164 | 37 | 7.09 (2.32) |

6.73 (2.78) |

13.97 (5.63) |

13.38 (6.07) |

20.73 (8.07) |

19.78 (9.57) |

| Central Africa | 191 | 48 | 7.31 (2.22) |

7.33 (2.33) |

14.35 (5.72) |

15.21 (5.11) |

20.41 (8.28) |

21.23 (8.59) |

| Southern Africa | 298 | 65 | 7.34 (1.81) |

7.08 (2.36) |

14.28 (4.62) |

14.37 (6.09) |

21.11 (7.11) |

20.80 (7.48) |

| Age category (years) | 1433 | 428 | 7.26 (2.10)** |

7.20 (2.21) |

13.76 (5.13)** |

13.82 (5.10) |

20.75 (7.62)* |

21.29 (7.84) |

| 18 to 28 | 561 | 175 | 7.01 (2.42) |

7.13 (2.40) |

13.25 (5.58) |

13.60 (5.63) |

19.95 (8.15) |

20.54 (8.15) |

| 29 to 38 | 391 | 109 | 7.44 (1.87) |

7.26 (2.07) |

14.16 (4.97) |

14.61 (4.24) |

20.99 (7.26) |

22.83 (6.78) |

| 39 to 48 | 310 | 91 | 7.34 (1.97) |

7.14 (2.26) |

13.69 (5.08) |

13.29 (5.13) |

21.27 (7.58) |

20.56 (8.37) |

| 49+ | 171 | 53 | 7.50 (1.51) |

7.38 (1.75) |

14.63 (3.74) |

13.87 (4.74) |

21.91 (6.35) |

21.89 (7.60) |

| Sex | 1434 | 429 | 7.25 (2.11) |

7.20 (2.21) |

13.73 (5.15) |

13.84 (5.09) |

20.72 (7.64) |

21.27 (7.85) |

| Male | 788 | 240 | 7.29 (2.09) |

7.30 (2.04) |

13.76 (4.85) |

13.80 (4.48) |

21.03 (7.40) |

21.41 (7.48) |

| Female | 646 | 189 | 7.21 (2.13) |

7.07 (2.41) |

13.70 (5.50) |

13.88 (5.41) |

20.35 (7.92) |

21.10 (8.31) |

| Marital status | 1438 | 429 | 7.25 (2.11)* |

7.20 (2.21) |

13.74 (5.15) |

13.83 (5.09) |

20.74 (7.65) |

21.30 (7.84) |

| Married | 636 | 186 | 7.40 (1.85) |

7.30 (1.96) |

13.96 (4.90) |

13.87 (4.71) |

21.05 (7.28) |

21.43 (7.39) |

| Not married | 802 | 243 | 7.13 (2.29) |

7.12 (2.38) |

13.56 (5.34) |

13.80 (5.38) |

20.49 (7.93) |

21.21 (8.18) |

| Highest level of education | 1439 | 430 | 7.26 (2.09) |

7.20 (2.21) |

13.76 (5.12) |

13.83 (5.09) |

20.77 (7.61) |

21.28 (7.84) |

| Postgraduate degree (master's/PhD) | 487 | 118 | 7.46 (1.72)*** |

7.50* (1.56) |

14.14 (4.53)* |

14.79 (3.71) |

21.16 (6.74)** |

22.19 (6.60)* |

| Bachelor's degree | 763 | 248 | 7.28 (2.08) |

7.20 (2.23) |

13.76 (5.15) |

13.65 (5.22) |

20.99 (7.70) |

21.38 (7.90) |

| Secondary/primary | 189 | 64 | 6.66 (2.81) |

6.64 (2.92) |

12.77 (6.12) |

12.80 (6.41) |

18.84 (8.99) |

19.19 (9.34) |

| Employment status | 1442 | 430 | 7.25 (2.12)* |

7.20 (2.21) |

13.73 (5.15) |

13.83 (5.09) |

20.72 (7.66) |

21.28 (7.84) |

| Employed | 957 | 275 | 7.33 (2.00) |

7.29 (2.02) |

13.98 (5.01) |

14.04 (4.68) |

20.92 (7.44) |

21.68 (7.53) |

| Unemployed | 485 | 155 | 7.09 (2.32) |

7.03 (2.50) |

13.24 (5.40) |

13.47 (5.75) |

20.34 (8.07) |

20.57 (8.36) |

| Religion | 1437 | 430 | 7.25 (2.11) |

7.20 (2.21) |

13.74 (5.14) |

13.83 (5.09) |

20.75 (7.64) |

21.28 (7.84) |

| Christianity | 1267 | 385 | 7.26 (2.09) |

7.23 (2.19) |

13.75 (5.14) |

13.95 (5.06) |

20.73 (7.66) |

21.22 (7.77) |

| Others | 170 | 45 | 7.17 (2.25) |

6.96 (2.34) |

13.74 (5.14) |

12.82 (5.28) |

20.88 (7.47) |

21.76 (8.53) |

| Do you live alone during COVID-19? | 1439 | 429 | 7.25 (2.10) |

7.20 (2.21) |

13.76 (5.13) |

13.83 (5.09) |

20.72 (7.63) |

21.28 (7.85) |

| No | 1168 | 355 | 7.29 (2.06) |

7.19 (2.19) |

13.79 (5.05) |

13.74 (5.13) |

20.76 (7.53) |

21.06 (7.72) |

| Yes | 271 | 74 | 7.10 (2.30) |

7.22 (2.32) |

13.62 (5.46) |

14.22 (4.91) |

20.56 (8.05) |

22.30 (8.43) |

| Number living together in 1 household | 1313 | 362 | 7.20 (2.19) |

7.15 (2.32) |

13.70 (5.25) |

13.68 (5.22) |

20.67 (7.77) |

21.06 (7.97) |

| <3 | 375 | 110 | 7.18 (2.25) |

7.24 (2.24) |

13.51 (5.25) |

14.02 (5.07) |

20.66 (7.68) |

21.17 (7.54) |

| 4 to 6 | 663 | 200 | 7.17 (2.19) |

7.08 (2.44) |

13.77 (5.30) |

13.38 (5.30) |

20.54 (7.79) |

20.95 (8.58) |

| 6+ | 275 | 52 | 7.31 (2.11) |

7.29 (1.99) |

13.80 (5.16) |

14.12 (5.29) |

21.00 (7.86) |

21.25 (6.40) |

| Attitude toward COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Self-isolation | 1300 | 388 | 7.76 (0.92) |

7.76 (1.01) |

15.33 (2.51)*** |

15.36 (2.46)*** |

22.63 (4.81) |

23.28 (4.92) |

| No | 899 | 267 | 7.76 (0.91) |

7.74 (1.07) |

14.98 (2.41) |

14.93 (2.28) |

22.62 (4.65) |

23.13 (5.02) |

| Yes | 401 | 121 | 7.77 (0.93) |

7.79 (0.86) |

16.11 (2.56) |

16.33 (2.58) |

22.66 (5.16) |

23.62 (4.70) |

| Home quarantined due to COVID-19 | 1298 | 387 | 7.76 (0.92) |

7.75 (1.00) |

15.34 (2.49)*** |

15.39 (2.43)*** |

22.63 (4.81) |

23.28 (4.93) |

| No | 794 | 233 | 7.78 (0.96) |

7.75 (1.02) |

14.92 (2.40) |

14.90 (2.25) |

22.56 (4.73) |

23.33 (5.03) |

| Yes | 504 | 154 | 7.74 (0.84) |

7.75 (0.97) |

16.02 (2.48) |

16.12 (2.51) |

22.75 (4.95) |

23.21 (4.77) |

| Risk perception | ||||||||

| How worried are you because of COVID-19? | 1471 | 433 | 7.20 (2.19)*** |

7.17 (2.24)*** |

13.64 (5.26)*** |

13.81 (5.13)*** |

20.56 (7.80)*** |

21.26 (7.90)*** |

| Very worried | 410 | 127 | 7.70 (0.84) |

7.80 (0.84) |

15.49 (2.88) |

15.49 (2.71) |

25.93 (4.39) |

26.29 (4.10) |

| Somehow worried | 496 | 140 | 7.84 (0.93) |

7.66 (1.19) |

14.66 (3.19) |

14.46 (3.64) |

20.38 (3.37) |

20.66 (3.50) |

| Not at all | 565 | 166 | 6.27 (3.13) |

6.28 (3.17) |

11.41 (6.99) |

11.98 (6.79) |

16.81 (9.98) |

17.92 (10.45) |

| Feeling about self-isolation | ||||||||

| Bored | 1181 | 359 | 7.19 (2.23) |

7.15 (2.23) |

13.59 (5.29) |

13.88 (5.11) |

20.53 (7.88) |

21.27 (7.98) |

| No | 343 | 112 | 7.22 (2.23) |

7.10 (2.33) |

13.71 (5.26) |

13.59 (5.43) |

20.72 (7.69) |

20.63 (8.39) |

| Yes | 838 | 247 | 7.18 (2.24) |

7.18 (2.19) |

13.54 (5.31) |

14.02 (4.96) |

20.45 (7.95) |

21.57 (7.78) |

| Frustrated | 1165 | 350 | 7.18 (2.25) |

7.15 (2.25) |

13.60 (5.34) |

13.89 (5.16) |

20.50 (7.96) |

21.30 (8.05) |

| No | 550 | 187 | 7.24 (2.16) |

7.14 (2.17) |

13.68 (5.23) |

13.94 (5.08) |

20.58 (7.77) |

20.88 (7.84) |

| Yes | 615 | 163 | 7.13 (2.33) |

7.15 (2.35) |

13.53 (5.45) |

13.85 (5.25) |

20.42 (8.12) |

21.79 (8.27) |

| Angry | 1128 | 334 | 7.20 (2.23) |

7.19 (2.21) |

13.59 (5.32) |

13.93 (5.15) |

20.47 (7.90) |

21.36 (8.03) |

| No | 862 | 279 | 7.20 (2.23) |

7.19 (2.25) |

13.57 (5.32) |

13.96 (5.17) |

20.54 (7.94) |

21.33 (7.98) |

| Yes | 266 | 55 | 7.18 (2.23) |

7.22 (1.99) |

13.65 (5.34) |

13.73 (5.10) |

20.25 (7.78) |

21.51 (8.38) |

| Anxious | 1153 | 353 | 7.19 (2.22) |

7.16 (2.25) |

13.57 (5.33) |

13.91 (5.15) |

20.49 (7.93) |

21.31 (8.02) |

| No | 480 | 134 | 7.33 (2.04) |

6.99 (2.30) |

13.85 (4.98) |

13.34 (5.54) |

20.85 (7.42) |

20.54 (8.45) |

| Yes | 673 | 219 | 7.10 (2.34) |

7.26 (2.21) |

13.37 (5.57) |

14.26 (4.87) |

20.22 (8.27) |

21.79 (7.74) |

| Note: P values are paired t test results of comparison of variables within groups. *P < .05, **P < .005, ***P < .0005. Abbreviations: HCW, healthcare worker; non-HCWs, non-healthcare workers; SD, standard deviation. |

||||||||

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using Stata version 14.1 (Stata Corp. College Station United States of America). KAP by independent variables were summarized using t-test for two categorical groups and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for more than two categorical groups.

Univariate linear regression analyses were conducted to assess the unadjusted coefficients (B) with 95% confidence intervals among HCWs and NHCWs. The adjusted coefficients (β) with 95% confidence intervals obtained from the multiple linear regression model were used to measure the factors associated with KAP among HCWs and non-HCWs.

For the multiple linear regression analyses, a four-staged modelling technique was conducted. In the first stage (Model 1) included regions and demographic factors and manual process backward stepwise elimination process was conducted and those with P< 0.05 were retained. The factors associated in Model 1 were added to Model 2, which was attitude towards COVID-19. The variables would influence action to reduce the spread of the infection and this was then followed by similar backward stepwise elimination procedure. The significant factors retained in Model 2 were included in Model 3, which was feeling about isolation during COVID -19 lockdown. This was because they would help in identifying individuals who could develop mental health issue during the lockdown. Manual process backward stepwise elimination process identified the associated factors in Model 3. The fourth and final model included addition of knowledge and attitude scores to Model 3, which were added because knowledge is strongly related to attitude and practice while knowledge and attitude has been reported to be associated with practice43.

Results

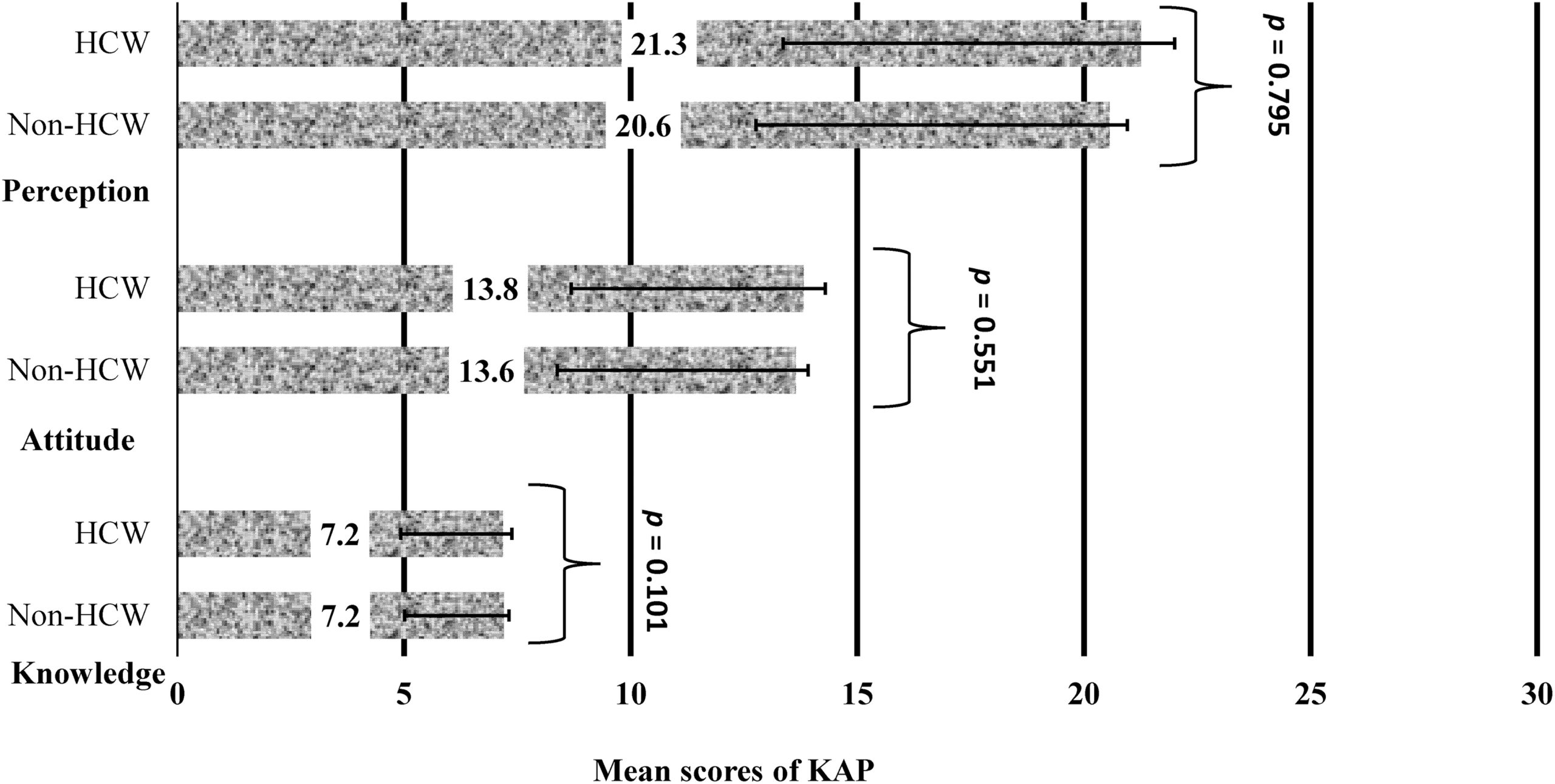

Figure 1. Mean scores for knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of COVID-19 among HCWs and non-HCWs in sub-Saharan Africa. Error bars are standard deviations. P values are results of comparison between both groups. Abbreviations: HCW, healthcare worker; KAP, knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions; non-HCW, non-healthcare worker.

Figure 1 presents the mean scores and their 95% confidence intervals for KAP among respondents who were NHCWs and HCWs. The mean score for knowledge (7.2 out of 12 points) and attitudes (13.7 out of 24 points) of COVID-19 were relatively high with low risk perception (20.7 out of 60 points) for contracting the disease. In figure 1, there was no significant difference between both groups for KAP scores.

Descriptive statistics

Majority of the respondents were NHCWs (77.0%, mostly teachers, managers and administrators; Supplementary Table S1) and 23.0% were HCWs. The breakdown of the responses are shown in Table 1 including the results of comparative analysis for the mean KAP scores. Most of the participants were single, men, aged between 18 and 38 years old, were from West Africa, and had completed University education or its equivalent, at the time of this study. 66.4% of HCWs and 64.0% of NHCWs were employed. About 40% of NHCWs and HCWs stated they voluntarily quarantined themselves during the lockdown period. Regarding their concern on the spread of the 2019-nCoV virus, about 62% of NHCWs and HCWs were worried about contracting the infection.

There were significant differences in mean scores between the age groups for NHCWs and between educational status, worried about contracting the infection, practised self-isolation and self-quarantined during the lockdown in both HCWs and NHCWs (see Table 1 for details).

Unadjusted coefficients of COVID-19 related knowledge, attitude and perception of risk of contracting the infection

The unadjusted coefficient for factors associated with COVID-19 related knowledge, attitude and perception are presented in the Supplementary material (S2). Among HCWs and NHCWs, older age was significantly associated with all three-outcomes. In HCWs and NHCWs, Southern and Central Africans had significantly higher attitude scores, those with secondary/primary education, not worried about contracting the infection reported a lower attitude scores. NHCWs who were unemployed had lower knowledge and attitude scores. In HCWs and NHCWs, knowledge and attitude were significantly associated with risk perception (see S2 for further details).

Factors associated with KAP during COVID-19 among HCWs and NHCWs

Table 2 shows the factors associated with KAP of COVID-19 in HCWs and NHCWs, after adjusting for the potential cofounders. Region of origin (Southern and Central Africa), age group (29-38 years) were significantly associated with high knowledge but lower education (primary/secondary) and not worried about COVID-19 were associated with low knowledge of

COVID-19 among NHCWs. For HCWs, lower education (primary/secondary) and not worried about COVID-19, were associated with low knowledge of COVID-19.

Table 2. Factors Associated with Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions of COVID-19 Among HCWs and Non-HCWs

| Knowledge | Attitude | Perception | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Non-HCW β (95% CI) |

HCW β (95% CI) |

Non-HCW β (95% CI) |

HCW β (95% CI) |

Non-HCW β (95% CI) |

HCW β (95% CI) |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Region (West Africa) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| East Africa | .06 (-0.28 to 0.39) |

– | 1.05 (0.63 to 1.47) |

.92 (0.09 to 1.76) |

-.44 (-1.22 to 0.35) |

– |

| Central Africa | .36 (0.04 to 0.67) |

– | 1.36 (0.96 to 1.75) |

1.61 (0.88 to 2.34) |

-.94 (-1.67 to -0.20) |

– |

| Southern Africa | .32 (0.06 to 0.59) |

– | .51 (0.18 to 0.84) |

1.00 (0.37 to 1.64) |

-.48 (-1.10 to 0.14) |

– |

| Age category in years (18 to 28 years) |

Reference | |||||

| 29 to 38 | .32 (0.04 to 0.60) |

– | – | – | – | – |

| 39 to 48 | .13 (-0.19 to 0.44) |

– | – | – | – | – |

| 49+ | .31 (-0.08 to 0.69) |

– | – | – | – | – |

| Highest level of education (postgraduate degree) |

Reference | Reference | Reference | – | – | |

| Bachelor's degree | -.02 (-0.28 to 0.23) |

-.38 (-0.90 to 0.13) |

– | -.56 (-1.08 to -0.03) |

– | – |

| Secondary/primary | -.43 (-0.81 to -0.04) |

-.95 (-1.69 to -0.22) |

– | -.42 (-1.18 to 0.34) |

– | – |

| Attitude toward COVID-19 | ||||||

| Self-isolation (No) | – | – | Reference | Reference | – | – |

| Yes | – | – | .71 (0.41 to 1.02) |

.97 (0.45 to 1.49) |

– | – |

| Home quarantined due to COVID-19 (No) | – | – | Reference | Reference | – | – |

| Yes | – | – | .83 (0.54 to 1.12) |

1.01 (0.51 to 1.50) |

– | – |

| Risk perception | ||||||

| How worried are you about COVID-19? (Very worried) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Somehow worried | .18 (-0.08 to 0.44) |

-.18 (-0.76 to 0.40) |

-.65 (-0.96 to -0.33) |

-.58 (-1.13 to -0.02) |

-5.29 (-5.91 to -4.67) |

-4.76 (-5.95 to -3.58) |

| Not at all | -1.27 (-1.53 to -1.01) |

-1.43 (-1.98 to -0.88) |

-.35 (-0.68 to-0.03) |

.04 (-0.51 to 0.60) |

-4.86 (-5.49 to -4.23) |

-4.39 (-5.58 to -3.20) |

| Feeling about self-isolation | ||||||

| Frustrated (No) | – | Reference | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | – | -.00 (-0.45 to 0.45) |

– | – | – | – |

| Knowledge score† |

– | – | .26 (0.12 to 0.41) |

.34 (0.11 to 0.57) |

1.28 (1.13 to 1.43) |

.96 (0.65 to 1.27) |

| Attitude score† |

– | – | – | – | .61 (0.55 to 0.67) |

|

| † = continuous variable. Bolded are significant variables. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HCW, healthcare workers; non-HCWs, non-healthcare workers. |

||||||

Compared to Western Africans, HCWs and non-HCWs from other SSA regions reported higher attitude scores towards COVID-19 (Table 2). Other factors associated with positive attitude towards COVID-19 mitigation practices were practice of self-isolation among NHCWs (β= 0.71, 95%CI 0.41, 1.02) and HCWs (β= 0.97, 95%CI 0.45, 1.49), self-quarantine among NHCWs (β= 0.83, 95%CI 0.54, 1.12) and HCWs (β= 1.01, 95%CI 0.51, 1.50) during the lockdown. High knowledge scores were associated with positive attitude for NHCWs (β=0.26, 95%CI 0.12, 0.41) and HCWs (β= 0.34, 95%CI 0.11, 0.57). Negative attitude towards COVID-19 mitigation practices was observed among HCWs who completed Bachelor education (β= -0.56, 95%CI -1.08, -0.03) and those and those who expressed some worry about contracting the infection (β= -0.58, 95%CI -1.13, -0.02).

There were significant associations between risk perception and knowledge of COVID-19 (β= 1.28, 95%CI 1.13, 1.43 for NHCWs and β= 0.96, 95%CI 0.65, 1.27 for HCWs) and attitude (β=0.61, 95CI 0.55, 0.67 for NHCWs). Those who were either somewhat worried or not worried at all had a lower risk perception of contracting the infection. NHCWs from Central Africa (β= -0.94, 95%CI -1.67, -0.20) had a lower risk perception than West Africans.

Discussion

The study found comparable KAP scores among NHCWs and HCWs in SSA. However, the SSA region of origin, age of respondents, level of education, and how worried they were about contracting COVID-19, were associated with knowledge of COVID-19 among NHCWs. On the other hand, level of education, worry about COVID-19 and feeling of frustration about self-isolation were associated with knowledge of COVID-19 among HCWs. There was a significant association between positive attitude towards COVID-19 practices and the SSA region of origin, practice of self-isolation and home quarantine as well as knowledge of COVID-19, among HCWs and NHCWs. In addition, lower risk perception for contracting COVID-19 was reported among NHCWs who lived in Central Africa and among HCWs and NHCWs who were somewhat worried or not worried about contracting COVID-19.

Past studies showed that the overall incidence of the COVID-19 pandemic was disproportionately higher among HCWs than the general population44. Inadequate training for HCWs on the control measures for this novel respiratory borne infectious disease has been cited for the increased risk among HCWs45. Following the initiation of emergency responses, HCWs found it difficult to make time for systematic training and practice, leaving them with a lack of relevant knowledge about the disease. This may have contributed to the lack of significant difference in the overall KAP scores between HCWs and NHCWs in this study. Although, it is expected that HCWs would exhibit better knowledge about the disease than NHCWs, no study has provided a statistical comparison of knowledge scores between the groups. A web-based descriptive study of university hospital staff including healthcare workers and administrative staff, in northern Italy, found an overall good knowledge on 2019-nCoV control measures in both groups (71.6% for HCWs and 61.2% for administrative staff), and noted the need to promote effective control measures and correct preventive behaviours at the individual level46. In other studies, greater knowledge of COVID-19 by HCWs correlated with their greater confidence to fight the pandemic37, 47 and their more positive attitudes48. The participants in this study (HCWs and NHCWs) responded to the same questionnaire. However, in another study where different questionnaires were administered to the HCWs and the general public, similar scores for knowledge and perception was found between the groups36, but there was a difference in their knowledge of COVID-19 treatment. The predominant sources of information differed between the groups, and the study did not assess their sources of information.

In this study, we found significant association between the knowledge of COVID-19 and being worried about contracting COVID-19, after adjusting for the confounding variables. HCWs and NHCWs who were not worried about contracting the infection, had lower knowledge of COVID-19 compared to those who were very worried about the disease. This finding suggests that, although HCWs may be knowledgeable about the disease, they may not be protected from the mental health effects, which are now being documented among health workers due to the pandemic4, 49, 50. It may actually be a risk factor as they have information about the disease but are not favourably disposed to the measures that need to be put in place to prevent the spread of the disease51. This was seen in the SARs outbreak where HCWs were found to have increased emotional distress that was associated with quarantine and isolation, among other factors52.

NHCWs who lived in Central and Southern African countries showed higher knowledge scores than those from the West African countries. This finding is consistent with a cross-sectional study carried out in five health communities in a Central African country (Cameroon) which showed that 65.7% of respondents had high knowledge53. In this study, positive attitude towards COVID-19 was also associated with living in the East, Central and Southern African regions for NHCWs, which was similar to the high KAP scores found among community drivers who participated in an online cross sectional study conducted in Uganda in East Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic54. Our findings of higher risk perception scores among West African respondents than the others, was supported by the findings of high risk perception of COVID-19 among Ghanaian adults, who participated in an electronic based cross-sectional survey55.

Another finding of this study was the more positive attitude towards COVID-19 practices reported by HCWs who lived in the East, Central and Southern African countries. This is consistent with the positive attitude towards COVID-19 prevention practices found among HCWs in Uganda East Africa39. Similar findings of positive attitude has been reported in Nigeria, West Africa, with some unacceptable practices in wearing of facemask during the COVID-19 pandemic among the HCWs56. SSA is a mix of persons of different tribes, cultures and beliefs and racial disparities in attitude towards COVID-19 have been documented57. During the Ebola epidemic in 2015 that swept the region, negative attitude was observed among West Africans, and this was influenced by misconceptions and perceived changes to culture. These same factors may be at play here in this current pandemic. The fact that educational background was consistently associated with lower attitude scores towards COVID-19 and other health matters57-60 has implications for control measures, as behavioural change health communication should be designed to target those with lower levels of education in the SSA population.

In this study, educational background was significantly associated with the KAP scores among NHCWs possibly, because HCWs were already the well-educated group in this study due to the requirements of their profession. As shown in the socio-demographics only 3.4% of the HCWs had less than a bachelor’s degree, hence significant differences would not be visible here. Additionally, NHCWs who practiced self-quarantine during the lockdown had more positive attitude than the HCWs. Unlike the public, many health workers were expected to report at their work stations during the pandemic hence may not self-quarantine unless asked to do so from exposure at the workplace and may result in them having a poorer attitude. NHCWs who were unemployed had poor attitude towards COVID-19 practices which may reflect the existing inequities in the labour market and the chronic stress and uncertainty created by unemployment that are believed to have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.61, 60

Worry is an affective, emotional response to a threat and can predict protective behaviours and attitudes independent of the risk severity62. Social isolation and loneliness are linked to both poor mental and physical health, such that isolation brings about feelings of anxiety, worry and depression. We found that being worried about contracting the infection led to poor attitude towards the public health measures put in place to contain the spread of the disease, among HCWs and NHCWs. There were significant associations between knowledge about COVID-19 and the perception of high risk for contracting the infection among both HCWs and NHCWs in this study. Similar to a previous study63, NHCWs who felt at risk of being infected by the disease showed positive attitude towards the preventive measures. A study on HCWs64 also found that despite the high positive attitude of the respondents, their risk perception for susceptibility to contracting the disease was also high. This may be explained by to the report that HCWs were afraid of infecting their family members, stigmatized, lacked the necessary personal protective equipment, had to deal with a public that is not committed to the preventive measures coupled with the poor ventilation and overcrowding at the workplace64.

This study has some limitations. The cross-sectional design of this study made it impossible to determine causation. Given the inability to physically access respondents due to the pandemic, the survey tool was sent out to prospective respondents electronically using social media platforms and emails. This method of soliciting respondents may have inadvertently excluded some potential participants whose opinion may have differed, such as those who without internet access, and people living in rural areas where internet penetration remains relatively low65. However, the use of an internet-based methodology was the only reliable means to disseminate information at the time of this study. Furthermore, the survey was presented in the English language and those from non-English speaking countries in SSA may not have participated. Notwithstanding these limitations, this was the first study from the SSA region to provide insight into the factors that influence KAP among NHCWs and HCWs as well as information about compliance with the public health control measures in this pandemic. The study used a robust analysis to control for potential confounders during the analysis in order to reduce the issue of bias.

Conclusion

In summary, although there was no significant difference in KAP among HCWs and non-HCWs, the study showed essential elements of variation between HCWs and non-HCWs. HCWs who felt frustrated about self-isolation during the lockdown period had significantly higher COVID-19 related knowledge than non-HCWs. For non-HCWs, employment status was associated with the level of COVID-19 related knowledge but this association was not observed among HCWs. The level of knowledge and attitude towards COVID-19 played significant roles in the respondents’ periceved risk of COVID-19 transmission. The findings of this study, indicate the importance of strengthening public health knowledge of workers in SSA towards COVID-19. Priority should be given to HCWs and unemployed non-HCWs. This approach would change the response of the target group to public health control measure and ultimately may lead to containment of the pandemic.

Notes

§ https://westernsydney.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/56/2023/08/supp_fig1-scaled.jpg

# https://westernsydney.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/56/2023/08/supp_table1.docx

References

Supplementary Materials

Attribution

All rights reserved. Copyright © 2021, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers.