Version of Record (VoR)

Osuagwu, U. L., Miner, C. A., Bhattarai, D., Mashige, K. P., Oloruntoba, R., Abu, E. K., … Agho, K. E. (2021). Misinformation about COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa : evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Health Security, 19(1), 44-56. https://doi.org/10.1089/HS.2020.0202

Article

Misinformation of COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa:

Evidence from online Cross-Sectional Survey

Running title: Misinformation of COVID-19 in Sub-Sahara Africa

Open access fee for this article was covered by World Health Organization (WHO) during the pandemic.

Abstract

Globally, misinformation about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) constitute a significant threat to public health because they could inadvertently exacerbate public health challenges by promoting the spread of the infection. This cross sectional study used convenience-sampling technique to examine factors associated with misinformation of COVID-19 in Sub-Sahara African (SSA) using an online cross-sectional survey. An e-link of the self-administered questionnaire was distributed to 1,969 participants through social media platforms and authors’ email networks. A pilot study informed the misinformation to be included. The four common misinformation were ‘COVID-19 was designed to reduce world population’, ‘holding one’s breath for 10 seconds is a sign of not having COVID-19′, ‘drinking hot water flushes down COVID-19’ and ‘COVID-19 has little effect(s) on Blacks than Whites’. The participants’ responses were classified as ‘Agree’, ‘Neutral’ and ‘Disagree’. A multinomial logistic regression was used to examine associated factors. The proportion of respondents who thought that ‘COVID-19 was designed to reduce world population’, ‘holding one’s breath for 10 seconds is a sign of not having COVID-19′, ‘drinking hot water flushes down COVID-19’ and ‘COVID-19 has little effect(s) on Blacks than Whites’ were 19.3%, 22.2%, 27.8% and 13.9%, respectively. Multivariate analysis revealed that those who thought COVID-19 was not likely to continue in their countries reported higher odds for the 4 misinformation about COVID-19. Other significant factors associated with belief in the misinformation were: Age (older respondents), employment (unemployed); gender (females), education (secondary/primary) and knowledge of main clinical symptoms of COVID-19. Strategies to reduce the spread of false information on COVID-19 and other future pandemic should target these subpopulations especially those with limited education. This will also enhance compliance with the public health measures.

Keywords: infodemic, COVID-19, sub-Saharan Africa, belief, myth

Introduction

There remains a great deal that is not known about the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and this limited scientific information has contributed to a slew of misinformation (1, 2). As the outbreak of the COVID-19 which started in Wuhan province of China in December of 2019 (3), spread rapidly across the world, so did the conversation about the disease (4). Similar to other challenges (e.g., global warming), the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic depends on the actions of individual citizens and, therefore, the quality of the information to which people are exposed. Notably, social media has been flooded with information regarding the origin and implications of coronavirus(4, 5). Unfortunately, a lot of information about the pandemic, its symptoms, transmission methods and response mechanisms have been unreliable (6-9). As a result, audiences have been treated to misinformation and misconceptions through propaganda and fake news that needs to be addressed.

Despite creating awareness and providing adequate information to the public through telecommunication (radio, television advertisements, public health messages by prominent celebrities and national leaders) and distributing pamphlets/signboards at public places about infection control measures and mode of spread of the infection, the misinformation around the disease remain. While some of these misinformation may be harmless, others can be potentially dangerous and could have implications for compliance with non-pharmaceutical preventive strategies prescribed for the control of the novel coronavirus (9, 10) and may affect the development and implementation of a possible treatment (11).

In this regard, the various health authorities [World Health Organization (WHO), African Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)] have listed some of the prevailing misinformation to increase awareness about the infection and have provided factual information about COVID-19 on their websites (7, 12, 13). Additionally, some of the claims made in terms of improvement or boosting of immunity against COVID-19 infection, are being challenged (7). All these have led to further confusion in the mind of the general population.

Our interest is in Sub-Sahara Africa countries where the pandemic arrived relatively late (8) and home to over one billion people (14% of the world’s population). The first confirmed case of COVID-19 infection in Sub Saharan African (SSA) countries was in Nigeria, on the 28th February 2020. By 1st April 2020, 43 of the 46 SSA countries had reported confirmed cases of COVID-19(14). Contrary to predictions of the greater infection rates of COVID-19 in the region (15), SSA remains one of the least affected regions, and this could be attributed to the demonstrated solidarity and collective leadership in acting quickly. For example, African leaders’ timely adaptation of preventive measures, the low international air traffic and lessons learnt from previous epidemics such as Ebola(16).

Considering the fragile healthcare systems, the catastrophic shortage of healthcare professionals(17), the drastic reduction (of 75%) in medical commodities and supplies following border closures and restrictions on exports(18), and financial resource limitations, the SSA region may still catch up with other regions of the world that are more affected by COVID-19(8). Vigilance is compulsory, and complacency should not be allowed while SSA needs to intensify its efforts to slow the spread of the pandemic by providing evidence-based information on the disease using the channels trusted by the people (19, 20) to counter the misinformation of the public, which will lay the foundation for sustained recovery (21, 22). Identifying participatory ways of working will also be needed to put an end to the disease.

Studies have reported that belief in pseudoscience and myths about mental disorders was associated with a lower likelihood of health-seeking behaviour in the general population and medical professionals in India (21), and in a review study of 66 articles, myth was a barrier to receiving hepatitis C treatment (22). Also, many parents in northern Nigeria avoided polio immunizations for their children because of the myth that vaccinations cause infertility. Dispelling these types of myths may result in behaviour change that could improve the health-seeking behaviour of people (21). In addition, recognizing and confronting misinformation head-on may serve to increase both peoples’ knowledge as well as their ability to accurately distinguish and remember both mythical and factual information (23).

In an experimental study of 1700 US adults, authors found that nudging people to think about accuracy nearly tripled the level of true discernment in participants’ subsequent sharing intentions (24) and thus is a simple way to tackle sharing of false information. The purpose of this study is to provide analysis of the common misinformation about COVID-19 spreading across English speaking countries in SSA and the underlying implications regarding the realities of “social distancing” and “use of facemask’ arising from such myths. The findings of this study will provide people with reliable information using valid scientifically backed answers, which they can use to counter the misinformation and misconceptions arising from myths in SSA.

Methodology

Ethical approval for the study was sought and obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Blinded for Review (BLINDED FOR REVIEW/HRP/HREC/2020/117). The study adhered to the tenets of the declaration of Helsinki regarding research involving human subjects, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to completing the survey. Participants were required to answer a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the consent question during survey completion to indicate their willingness to participate in this study. All those who agreed to voluntarily participate in the survey were included in the study. The confidentiality of participants was assured in that no identifying information was obtained from participants.

Survey questionnaire

The survey tool for the COVID-19 knowledge question was developed based on the guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO) for clinical and community management of COVID-19. The questionnaire was adapted with some modifications to arrive at the type of information and misinformation, obtain information on the respondent’s attitude towards the mitigation practices, and their potential impact on compliance with strategies to control the spread of the novel coronavirus and risk perception of contracting COVID-19.

Prior to launching of the survey, a pilot study was conducted to ensure clarity and understanding as well to determine the duration for completing the questionnaire. Participants (n=10) from different English speaking countries in SSA who took part in the pilot were not part of the research team and did not participate in the final survey as well. The pilot also informed the misinformation to include in the final survey. This self-administered online questionnaire consisted of 36 items divided into four sections (demographic characteristics, knowledge, perception and practice). Supplementary Table 1 is a sample of the survey. All questions relating to demography were mandatory.

Recruitment

The participants were sub-Saharan African nationals from different African countries either living abroad or in their countries of origin including Ghana, Cameroun (only distributed to the English speaking regions), Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda etc. The survey was only available in English language such that participants were mostly from English speaking countries in SSAs. To be eligible for participation, participants had to be 18 years and over, and should be able to provide online consent.

Survey distribution

This study was a cross-sectional survey that utilized a convenience sampling technique. An e-link of the structured synchronized questionnaire was posted on social media platforms (Facebook and WhatsApp) which were commonly used by the locals in the participating countries, and was sent via emails by the researchers to facilitate response. Participants were also encouraged to share the e-link with their African networks. The survey was online for four weeks (between April 18 and May 16, 2020) when most of the countries in SSA were under mandatory lockdown and restriction of movement. As it was not feasible to perform nationwide community-based sample survey during this period, the data were obtained electronically via survey monkey. Only participants who had access to the internet, were on the respective social media platforms and used them, may have participated.

The questionnaire included a brief overview of the context, purpose, procedures, nature of participation, privacy and confidentiality statements and notes to be filled out(25). To avoid multiple responses, participants were instructed not to complete the questionnaire twice if they had participated previously. All the eligible participants completing the survey when it was online were included in the study.

In order to further minimise bias, this online survey used a Likert scale with provisions for neutral responses, so that the answers were not influenced in one way or another. The participants did not receive any incentives, their responses were voluntary and anonymized. Testing for the internal validity of the survey items, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient score ranged from 0.70 to 0.74 indicating satisfactory consistency.

Outcome variables

There were four main outcome variables in this study, which were misinformation about COVID-19. The misinformation were those popular among online users in sub-Sahara African countries as informed by our initial pilot study. The questions included whether or not respondents thought that a) COVID-19 was designed to reduce the world population, b) COVID-19 has little effect(s) on Blacks than on Whites?, c) the ability to hold one’s breath for 10 seconds, is a sign that they don’t have COVID-19 and d) drinking hot water flushes down the virus.

Covariates

Demographic variables: This included age, gender, marital status, location, education, employment, occupation, religion.

Knowledge of common symptoms of COVID-19: These were included to account for the shifting knowledge about the disease in the analysis. Questions included whether or not the participants could identify the common symptoms of COVID-19 as listed by the WHO as the main clinical symptoms of the disease (fever, dry cough and fatigue)(26) at the time of this study and how these symptoms differ from the common cold symptoms.

Attitude towards COVID-19 variables: The variables were included because it will influence action to reduce the spread of the infection. They were obtained from survey items inquiring on the practice of self-isolation, home quarantine, number of people living together in the household.

Compliance to the precautionary public health measure variables: To understand respondents compliance to the precautionary measures put in place to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 during the lockdown, the respondents were asked: “whether they have gone to any crowded place, including religious events” “if they wore a mask when leaving home”, and “if in recent days, they have been washing their hands with soap for at least 20 seconds each time or using hand sanitizers”. Each question used a Likert scale with five levels. The scores for each item ranged from 0 (lowest) to 4 (highest). These questions were necessary to identify individuals who will violate the lockdown laws in protecting and preventing the spread of the virus.

Risk perception variables: The survey items for risk perception asked the respondents: if they thought they were ‘at risk of becoming infected’, ‘at risk of dying from the infection’, ‘worried about contracting COVID-19’, and if they thought ‘the infection would continue in their country’. These were included because individuals who perceived the risk are more likely to reduce the spread of the virus.

Statistical analysis

Data cleaning, sorting, and processing were carried out before commencing the analyses. Tabulation was used to determine the prevalence and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals of the 4 misinformation variables of COVID-19 pandemic. Over one-third of respondents indicated ‘neutral’ and adding this category to either the ‘agree’ or the ‘disagree’ category, would bias the study findings (27) and the policy implication of this study. The responses to these 4 misinformation of COVID-19 were categorised as “Agreed (coded as ‘2’), “Neutral (coded as ‘1’) or “Disagreed (coded as ‘0’). Univariate and multivariate multinomial logistic regression were used to determine factors associated after controlling for individual confounding variables.

Multinomial logistic regression (MLR) using manual process stepwise backwards model was used in order to identify the factors associated with the 4 misinformation of COVID-19 pandemic. The results were presented as unadjusted (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). All variables with statistical significance of p ≤ 0.05 were retained in the final model as the adjusted odds ratios (AOR), and analyses were performed in Stata version 14.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows the detailed summary of the participant’s characteristics in this study. Overall, there were a total of 1,969 participants (55.2% males and 44.8% females) who responded to this survey and their proportion by age were 39.0% for 18-28 years, 26.7% (29-38 years), 22.2% (39-48 years) and 12.1% (49+ years). A little over half of the respondents were from West Africa (n=1,108, 56.3%) and few from East Africa (n = 209, 10.6%). More than two-third of the participants (79.2%) had at least a Bachelor degree while 20.8% had either a secondary or primary (basic) school education. While majority of the participants (>81%) correctly identified fever, dry cough and fatigue as the main clinical symptoms of the disease at the time of this study, their responses were split on whether participants with COVID-19 were less likely to experience the symptoms of common cold (50.7% versus 49.3%).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Demography | |

| Region | |

| West Africa | 1,108 (56.3) |

| East Africa | 209 (10.6) |

| Central Africa | 251 (12.7) |

| Southern Africa | 401 (20.4) |

| Place of residence | |

| Locally (Africa) | 1855 (92.5) |

| Diaspora | 150 (7.5) |

| Age category (years) | |

| 18-28 | 775 (39.0) |

| 29-38 | 530 (26.7) |

| 39-48 | 441 (22.2) |

| 49+ | 242 (12.1) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1099 (55.2) |

| Female | 892 (44.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 879 (44.1) |

| Unmarried | 1116 (55.9) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Postgraduate degree (master's/PhD) | 642 (32.2) |

| Bachelor's degree | 939 (47.0) |

| Primary/secondary | 416 (20.8) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 1321 (66.0) |

| Unemployed | 679 (34.0) |

| Religion | |

| Christian | 1763 (88.4) |

| Others | 232 (11.6) |

| Occupation | |

| Nonhealthcare sector | 1471 (77.3) |

| Healthcare sector | 433 (22.7) |

| Number of people living together in 1 household | |

| <3 people | 506 (28.8) |

| 4-6 people | 908 (51.7) |

| 6+ people | 341 (19.4) |

| Knowledge of symptoms of COVID-19 | |

| Fever | |

| No | 36 (2.0) |

| Yes | 1776 (98.0) |

| Fatigue | |

| No | 324 (18.7) |

| Yes | 1408 (81.3) |

| Dry cough | |

| No | 324 (2.8) |

| Yes | 1759 (97.2) |

| Sore throat | |

| No | 215 (12.0) |

| Yes | 1,580 (88.0) |

| Unlike cold symptoms | |

| No | 907 (49.3) |

| Yes | 931 (50.7) |

| Attitude toward COVID-19 | |

| Self-isolation | |

| No | 1237 (66.7) |

| Yes | 564 (31.3) |

| Home quarantined due to COVID-19 | |

| No | 1091 (60.7) |

| Yes | 707 (39.3) |

| Compliance during COVID-19 lockdown | |

| Gone to crowded places including religious events | |

| No | 1097 (54.0) |

| Yes | 935 (46.0) |

| Wore mask when going out | |

| No | 485 (23.9) |

| Yes | 1547 (76.1) |

| Practiced regular handwashing | |

| No | 762 (37.5) |

| Yes | 1270 (62.5) |

| COVID-19 risk perception | |

| Risk of becoming infected | |

| High | 669 (37.2) |

| Low | 1128 (62.8) |

| Risk of becoming severely infected | |

| High | 466 (25.9) |

| Low | 1333 (74.1) |

| Risk of dying from the infection | |

| High | 349 (19.5) |

| Low | 1445 (80.6) |

| How worried are you because of COVID-19? | |

| Worried | 1037 (57.5) |

| Not worried | 766 (42.5) |

| How likely do you think COVID-19 will continue in your country? | |

| Very likely | 1152 (64.0) |

| Not very likely | 649 (36.0) |

| Concern for self and family if COVID-19 continues | |

| Concerned | 1667 (94.2) |

| Not concerned | 102 (5.8) |

Prevalence of misinformation about COVID-19

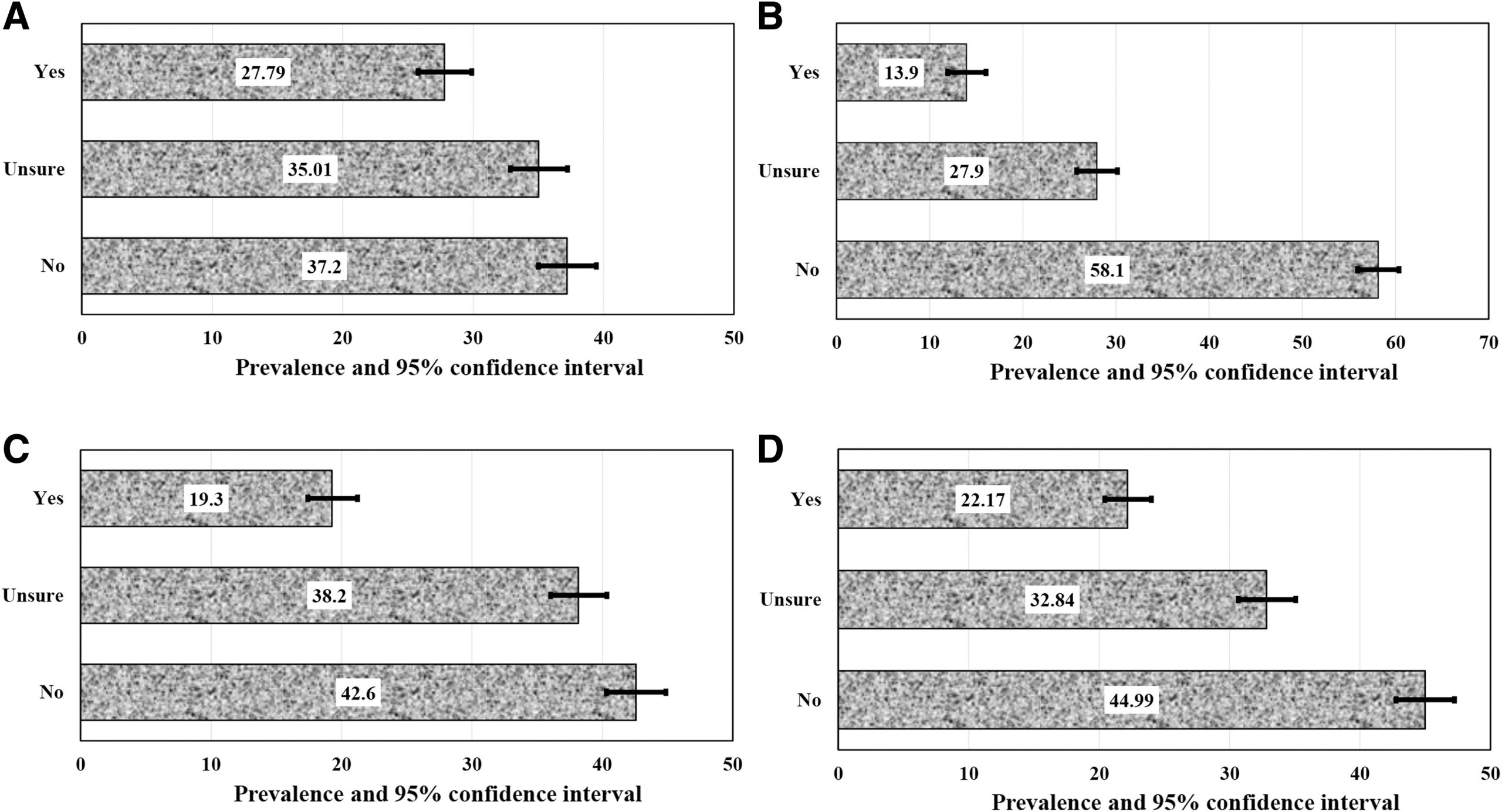

Figure 1(a-d) presents the prevalence of the 4 misinformation regarding COVID-19 which are: “belief that drinking hot water flushes down the COVID-19”, “belief that the infection has less effects on Blacks than on Whites”, “belief that COVID-19 is designed to reduce the world population”. The figures show that 28% of the respondents thought that drinking hot water flushes down the virus and this was followed by 22% who thought that the ability to hold one’s breath for 10 seconds is a sign that the person does not have COVID-19 infection. Nineteen percent of the respondents believed that COVID-19 was designed to reduce the world population, while more than one-third of the respondents (38%) were unsure about these misinformation. On whether the participants thought that COVID-19 has little effect on Blacks than Whites, 14% upheld this belief and another 30% were undecided about this misinformation.

Figure 1. Prevalence of belief in false statements related to COVID-19: (a) drinking hot water flushes down the virus; (b), COVID-19 has little effect on Blacks compared with Whites; (c) COVID-19 was designed to reduce world population; and (d) the ability to hold your breath for 10 seconds means you don’t have COVID-19.

Beliefs in 4 False Statements About COVID-19 – Unadjusted odd ratios of the 4 misinformation regarding COVID-19 in SSA

The unadjusted odd ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the 4 misinformation regarding COVID-19 are presented in Supplementary Tables (S2, S3, S4 and S5, respectively). Table S2 shows that age (39-48 years), marital status, religion, level of education (bachelor degree), non-compliance with the public health measures, and level of perceived risk and continuity of the infection were significantly associated with the belief that drinking hot water flushes down COVID-19.

The factors associated with the belief that COVID-19 has little effect(s) on Blacks than on Whites (Table S3) included age, region of residency (East Africa), employment status, marital status, religion, education level, non-compliance with the public health measures, and level of perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 infection. In addition to these variables, gender played a significant role in peoples belief on the misinformation that COVID-19 is designed to reduce the world population (Table S4). With regards to the factors associated with the belief that the ability to hold ones breath for 10 seconds means you do not have COVID-19 (Table S5), region of residency, and the level of perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 were the significant variables. These associated factors were further analysed after adjusting for the potential confounders.

Table 2. Multinomial Logistic Regression of Factors Associated with Misinformation Related to COVID-19

| Neutral | Agree | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | AOR (95% CI) | P Value | AOR (95% CI) | P Value |

| a. Factors associated with belief in false statement 1: Drinking hot water flushes down the virus | ||||

| Demography | ||||

| Age category (years) | ||||

| 18-28 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 29-38 | 1.42 (0.99-2.03) |

0.056 | 1.86 (1.25-2.77) |

0.002 |

| 39-48 | 2.22 (1.47-3.36) |

<.001 | 3.61 (2.30-5.67) |

<.001 |

| 49+ | 1.86 (1.16-3.00) |

0.011 | 3.16 (1.90-5.26) |

<.001 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Unemployed | 1.62 (1.16-2.27) |

0.005 | 1.72 (1.19-2.50) | 0.004 |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Others | 0.64 (0.44-0.93) | 0.02 | 0.67 (0.45-1.01) |

0.053 |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| Postgraduate degree (master's/PhD) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Bachelor's degree | 1.83 (1.36-2.45) |

<.001 | 1.84 (1.35-2.51) |

<.001 |

| Primary/secondary | 0.93 (0.58-1.49) |

0.771 | 1.36 (0.83-2.22) |

0.217 |

| Knowledge of symptoms of COVID-19 | ||||

| Fatigue | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.88 (0.64-1.19) |

0.404 | 0.69 (0.50-0.96) |

0.025 |

| Sore throat | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.60 (1.12-2.30) |

0.010 | 1.71 (1.15-2.54) |

0.008 |

| Compliance during COVID-19 lockdown | ||||

| Gone to crowded place including religious events | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.25 (0.98-1.60) |

0.069 | 1.36 (1.05-1.77) |

0.02 |

| COVID-19 risk perception | ||||

| If COVID-19 continues, how concerned would you be that you or family would be directly affected? | ||||

| Concerned | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Not concerned | 1.05 (0.64-1.73) |

0.836 | 0.69 (0.39-1.24) |

0.215 |

| How likely do you think COVID-19 will continue in your country? | ||||

| Likely | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Not likely | 1.74 (1.35-2.24) |

<.001 | 1.90 (1.45-2.48) |

<.001 |

| b. Factors associated with belief in false statement 2: COVID-19 has little effect on Blacks compared with Whites | ||||

| Demography | ||||

| Subregion | ||||

| Southern Africa | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Central Africa | 1.36 (0.93-1.97) |

0.111 | 1.37 (0.85-2.22) |

0.201 |

| East Africa | 1.30 (0.90-1.88) |

0.165 | 2.07 (1.36-3.15) |

0.001 |

| West Africa | 1.31 (0.98-1.73) |

0.065 | 0.95 (0.63-1.42) |

0.793 |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Others | 0.63 (0.43-0.93) | 0.02 | 0.61 (0.36-1.03) | 0.065 |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| Postgraduate degree (master's/PhD) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Bachelor's degree | 1.43 (1.11-1.84) |

0.006 | 1.34 (0.96-1.87) |

0.088 |

| Primary/secondary | 1.07 (0.72-1.59) |

0.731 | 1.14 (0.69-1.89) |

0.602 |

| Knowledge of symptoms of COVID-19 | ||||

| Fever | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.43 (0.20-0.92) |

0.03 | 0.41 (0.16-1.05) |

0.064 |

| Compliance during COVID-19 lockdown | ||||

| Gone to crowded place including religious events | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.28 (1.01-1.61) |

0.042 | 1.35 (0.99-1.82) |

0.053 |

| Handwashing/used hand sanitizer | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.77 (0.60-0.98) |

0.035 | 0.62 (0.45-0.84) |

0.002 |

| COVID-19 risk perception | ||||

| How likely do you think COVID-19 will continue in your country? | ||||

| Likely | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Not likely | 1.88 (1.48-2.38) |

<.001 | 2.53 (1.87-3.42) |

<.001 |

| c. Factors associated with belief in false statement 3: COVID-19 was designed to reduce world population | ||||

| Demography | ||||

| Age category (years) | ||||

| 18-28 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 29-38 | 1.13 (0.81-1.57) |

0.475 | 0.63 (0.42-0.94) |

0.024 |

| 39-48 | 0.97 (0.67-1.42) |

0.882 | 0.48 (0.30-0.79) |

0.004 |

| 49+ | 0.86 (0.56-1.32) |

0.489 | 0.43 (0.24-0.76) |

0.004 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.11 (0.89-1.38) |

0.368 | 1.54 (1.17-2.02) |

0.002 |

| Subregion | ||||

| Southern Africa | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Central Africa | 1.16 (0.80-1.68) |

0.44 | 1.45 (0.93-2.27) |

0.104 |

| East Africa | 1.55 (1.08-2.21) |

0.017 | 1.68 (1.10-2.56) |

0.016 |

| West Africa | 0.99 (0.75-1.31) |

0.964 | 0.85 (0.60-1.21) |

0.375 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Unemployed | 1.54 (1.12-2.11) |

0.008 | 1.85 (1.28-2.68) |

0.001 |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| Postgraduate degree (master's/PhD) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Bachelor's degree | 1.43 (1.10-1.85) |

0.007 | 1.69 (1.17-2.43) |

0.005 |

| Primary/secondary | 1.07 (0.69-1.64) |

0.771 | 1.30 (0.78-2.19) |

0.317 |

| Compliance during COVID-19 lockdown | ||||

| Gone to crowded place including religious events | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.32 (1.06-1.66) |

0.015 | 1.18 (0.89-1.56) |

0.259 |

| COVID-19 risk perception | ||||

| How likely do you think COVID-19 will continue in your country? | ||||

| Likely | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Not likely | 2.00 (1.59-2.51) |

<.001 | 1.55 (1.16-2.07) |

0.003 |

| d. Factors associated with belief in false statement 4: The ability to hold your breath for 10 seconds means you don't have COVID-19 | ||||

| Demography | ||||

| Subregion | ||||

| Southern Africa | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Central Africa | 1.05 (0.72-1.52) |

0.803 | 0.59 (0.37-0.94) |

0.026 |

| East Africa | 1.20 (0.84-1.72) |

0.32 | 1.09 (0.74-1.62) |

0.655 |

| West Africa | 0.94 (0.70-1.27) |

0.702 | 0.72 (0.52-0.99) |

0.049 |

| Number of people living together in 1 household | ||||

| <3 people | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 4-6 people | 1.34 (1.01-1.76) |

0.04 | 1.23 (0.91-1.66) |

0.186 |

| 6+ | 1.18 (0.84-1.65) |

0.353 | 0.82 (0.56-1.23) |

0.339 |

| Knowledge of symptoms of COVID-19 | ||||

| Unlike cold symptoms | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.77 (0.61-0.97) |

0.026 | 0.85 (0.65-1.11) |

0.226 |

| COVID-19 risk perception | ||||

| How worried are you because of COVID-19? | ||||

| Worried | 1 | 1 | ||

| Not worried | 0.86 (0.68-1.10) |

0.228 | 0.74 (0.56-0.97) |

0.027 |

| How likely do you think COVID-19 will continue in your country? | ||||

| Likely | 1 | 1 | ||

| Not likely | 2.09 (1.63-2.68) |

<.001 | 1.75 (1.32-2.31) |

<.001 |

| Note: Variables set in bold are common factors associated with the belief or uncertainty in the false statements about COVID-19. Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. |

||||

Factors associated with the 4 misinformation regarding COVID-19 in SSA

Table 2 (a-d) shows the factors associated with the four misinformation variables of the pandemic. Analysis of the factors associated with belief in these misinformation is presented below

Factors associated with the belief that drinking hot water flushes down the COVID-19 virus.

Table 2a revealed the factors associated with the belief that drinking hot water flushes down the COVID-19 virus. Older respondents, those who were unemployed and those who had a bachelor’s degree was more likely to belief that drinking hot water flushes down the COVID-19 virus. The odds of believing that drinking hot water flushes down the COVID-19 was lower among participants who correctly identified fatigue (AOR=0.69, 95%CI [0.50, 0.96]) and higher among those who wrongly identified sore throat (AOR=1.71, 95%CI [1.15, 2.54]) as one of the main clinical symptoms of the disease at the time of this study. Non-compliance with the precautionary health measure urging people to avoid attending crowded places, including religious events, increased the odds of the belief that drinking hot water flushes down the COVID-19 virus (AOR=1.36, 95% CI [1.05, 1.77]). Those who perceived that the COVID-19 is not likely to continue in their countries were about 2 times more likely to agree with this misinformation compared to other respondents (AOR=1.90, 95% CI [1.45, 2.48]). Similar trend of significance was observed in the ‘neutral’ or ‘no response’ group. Respondents were more likely to be neutral to this misinformation if they were older, unemployed, non-Christians, bachelor degree holders, visited crowded places during the lockdown and thought that COVID-19 was not likely to continue in their countries after the lockdown.

Factors associated with the belief in COVID-19 that “the infection has less effects on Blacks than on Whites”

Table 2b also shows that East African respondents were more likely to agree with the misinformation that COVID-19 had less effects on Blacks than on Whites compared to Southern Africans (AOR = 2.07, 95% CI [1.36, 3.15]). The respondents who did not wash their hands or did not use hand sanitizer were more likely to agree with this misinformation. Similarly, the respondents who perceived that COVID-19 was not likely to continue in their country (AOR =2.53, 95% CI [1.87, 3.42]) had a higher likelihood of reporting Blacks are less affected. Similarly, a significant proportion of respondents who held a bachelor degree (AOR =1.43, 95% CI [1.11, 1.84]), non-Christians, respondents who visited crowded places during the lockdown and those who thought that COVID-19 will not continue in their respective countries, were more likely to stay neutral on the belief that COVID-19 has little effect(s) on Blacks than on Whites. Respondents who were unsure of the common clinical symptoms of the disease had a lower odds of belief in this misinformation.

Factors associated with the belief in COVID-19 misinformation that “COVID-19 is designed to reduce the world population.”

Female respondents and those with lower education were more likely to agree that COVID-19 was designed to reduce the world population (see Table 2c for details). There were significant associations between belief in this misinformation and residents from the East African region. The respondents who did not perceive the continuing risk of the COVID-19 in their countries were more likely to agree to the statement (AOR =1.55, 95% CI [1.16, 2.07]). There was a similar trend of significance in the ‘neutral’ group concerning their belief on the misinformation. East Africans, those who were unemployed (AOR =1.54, 95%CI [1.12, 2.11]), visited crowded places or religious events (AOR =1.32, 95% CI [1.06, 1.66]) and those who thought the disease will not continue in their countries, were more likely to be neutral on the opinion that COVID-19 is designed to reduce the world population.

Factors associated with the belief in COVID-19 misinformation that “the ability to hold one’s breath for 10 seconds means you do not have COVID-19.”

As shown in Table 2d, Central and West African respondents were less likely to believe that holding one’s breath for 10 seconds means that the person does not have COVID-19 compared to Southern Africans (AOR=0.59, 95%CI [0.37, 0.94]; AOR=0.72, 95%CI [0.52, 0.99]). Similarly, the respondents who were worried about contracting COVID-19 and that who did not perceive continuing risk of the COVID-19 in their countries, were more likely to agree and more likely to be indecisive with regards to this misinformation. The association between the household factors (living with 4 to 6 people) and respondents who neither agreed nor disagreed with the opinion that one’s ability to hold his/her breath for 10 seconds means that they do not have COVID-19 was also significant (AOR=1.34 95%CI [1.01, 1.76]). Also, respondents who thought that COVID-19 will not continue in their respective countries were about two times more likely to stay neutral with regards to their belief in this misinformation when compared to those who thought that the disease will continue in their countries. Knowledge of the common clinical symptoms of COVID-19 was associated with a reduced risk particularly among those who were neutral to this misinformation.

Discussion

This study assessed four common misinformation and myths relating to the current COVID-19 pandemic and their determinants across English speaking countries in SSA. We found that about one in every five participants (21%) in this study believed the misinformation that drinking hot water flushes down COVID-19 and that one’s ability to hold his/her breathe for 10 seconds is a sign that they do not have COVID-19. Some participants also believed that COVID-19 has relatively little effect(s) on Black people than White people, and that the disease was designed to reduce the world population. In addition, a reasonable proportion of the participants were unsure as to whether the misinformation were true. The common factors associated with belief in the misinformation were older age, females, East African origin and unemployment. In addition to these factors, those who were knowledgeable about the common clinical symptoms of COVID-19 had lower odds of belief in the misinformation. Participants who held any of these beliefs demonstrated low-risk perception for contracting the infection and poor attitude towards the WHO precautionary public health measures put in place to contain the spread of the infection in their countries.

The study showed that misinformation about COVID-19 pandemic were predominant among the older population in SSA particularly the English speaking countries in SSA, who are indeed the most at-risk population to develop severe complications due to the COVID-19 infection (28). This finding is corroborated by a recent study, which found that older adults are up to 7 times more likely to share fake news and dubious links than their younger counterparts (29). To more effectively target the spread of misinformation among older adults, there is need to look more closely at interpersonal relationships and digital literacy. In addition to the fact that older people are less likely to use social platforms than younger generations, they tend to have fewer people on the edges of their social spheres, and tend to trust the people they do know more (29).

In previous studies, belief in misinformation about COVID-19 was associated with a poor attitude towards the public health precautionary measures, which ultimately can lead to increased COVID-19 infections (30, 31), as well as lead to psychosocial, economic and ethical consequences (32). Respondents who were unemployed were more likely to believe in the misinformation about COVID-19, and as shown in a previous study, individuals with low incomes had a higher risk of mortality due to the COVID-19 infection (33). Therefore, it is imperative that public health efforts of combating COVID-19 should integrate targeted interventions to specific population sub-groups to ensure their effectiveness in a high-risk population. For instance, corroborating accountable mass media that disseminates socially and culturally acceptable preventives measures of COVD-19 not only can mitigate the misinformation but also can reduce the mental health impacts of COVID-19 among older population(34). Also, health communication that starts by fostering well-being and basic human psychological needs has the potential to cut through the infodemic and promote effective and sustainable behaviour change during a pandemic(35).

The finding that respondents from East Africa were more likely to agree with most of the misinformation of COVID-19 was not surprising. Despite imposing curfews, partial and full lockdowns, and enforcing physical distancing in Tanzania, President John Magufuli still believed that COVID-19 is the work of the devil. During the lockdown, he encouraged people to attend public worship in churches and mosques, insisting that ‘prayer can defeat coronavirus disease’(36). On the other hand, Kenya, the closest neighbour to Tanzania, had earlier on introduced a national media and information literacy (MIL) policy into their national school curriculum, and took specific actions recently to apply these policies in order to combat COVID-19 disinformation. It is anticipated that MIL policies will help create a media literate population with capacity and skills for access to quality information, which the citizens need to make informed decisions within the new media and information environment(37). Although there are no evidence on the impact of introducing this initiative on misinformation spread during COVID-19, the Kenyan government through the support of UNESCO held several training targeting media practitioners, regulators and stakeholders during the pandemic. Training was conducted to improve the quality of journalism, and to provide trusted sources of information for the enhancement of MIL (37).

Non-compliance with the public health measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, such as avoiding crowds and practising good hand hygiene, was associated with belief in the misinformation of the pandemic. In the current COVID-19 crisis with the non-existence of the vaccine for all people, avoiding large gatherings, keeping good hand hygiene and use of facemask are the main public health directives in place to control the widespread of the outbreak. Public health initiatives to reduce the misinformation among the general population can prevent the violation of measures put in place to mitigate the spread of the pandemic. Social media could be an effective tool to promote health literacy among any targeted population using best evidence health literacy strategies, for instance the adaptation of plain language techniques(38). Mass campaigns using social media platforms with clear messages to encourage social distancing and wearing facemasks by the public health and local authorities can prevent the uncontrolled spread of the virus (39). While it is important to provide correct information about COVID-19, it is even more vital that such information are provided using trusted sources such as the government-owned broadcast media (40), use of celebrities(19) and trained community health advisors (20).

The belief that COVID-19 was deliberately developed and spread is common not only in the low-income countries (41) but also in the high-income countries like the USA and Australia (42, 43). A study conducted in the USA showed that around one-third of the respondents agreed to this misinformation (42). More than half of the participants in our study were either in agreement with a similar misinformation that COVID-19 was designed to reduce the world population or were undecided as to whether this information was true or false. Again, East Africans, females, the unemployed and people with a university degree were more likely to agree or remain undecided about this misinformation.

This study has some limitations. The survey was conducted using an online survey. It may not be a true reflection of the opinion of those living in rural areas where internet penetration remains relatively low (44). Since respondents are self-selected, there is no way to differentiate characteristics of respondents and non-respondents and it is difficult to completely prevent multiple responses of one person(45) even though respondents were instructed not to attempt the survey more than once. Although the study may not have captured the opinion of the older people who are less likely to use internet compared to younger ones(45), this was the only reliable means to disseminate information at the time of this study and provided an innovative way to give real-time data on the current situation. However, studies have found an increase in the use of internet among the general population during the pandemic (46), and it is less likely that this may have significantly impacted the results presented. In addition, the reduced cost and the availability of the survey to a great number of people, at any time of the day as well as the data being processed in real-time make online surveys a preferred data collection tool at this period and setting. The survey was available only in English, and some respondents from French-speaking countries did not participate. The participation of respondents from East Africa may have been affected by the lockdown as citizens from Kenya and Tanzania were asked to refrain from giving out information regarding the pandemic, which may have resulted in the wide variation in the response rate per region. Another limitation of this study was the use of a ‘neutral’ option in the questionnaire without specifically defining what selecting this option indicates in the questionnaire. In a previous study, the authors found that the selection of the neutral option may be measuring different attitudes and that participants tend to over use this option in questionnaires. They also noted that providing respondents with the neutral option would minimise response bias (27). There were no incentives given to participants in this study, and no assistance was sought from online companies during the distribution of the survey, which may have affected the reach of the survey. Lastly, this study is limited by the fact that it did not examine the changing symptom profiles and knowledge about COVID-19 which has evolved over time. However, future research looking at the misinformation should consider the changing profile in knowledge of the disease and symptoms, and how that affect peoples’ belief in the misinformation. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to provide robust and comprehensive evidence of the common misinformation of COVID-19 in English speaking countries in SSA region. Previous studies describing other misinformation did not explain how such beliefs are related with each other, and the factors associated and lack the robust statistical analysis to explore how such misinformation and other variables are related (47). In addition, efforts were made to minimise bias in this online survey.

Conclusion

The misinformation of COVID-19 is prevalent among East Africans and is associated with older age, females and those who are unemployed. There is a clear association between susceptibility to misinformation and knowledge about the clinical symptoms of COVID-19, low-risk perception of contracting the infection as well as a reduced likelihood to comply with public health measures. The study points to the obvious need to combat the infodemic of COVID-19 across English speaking countries of SSA by raising health and information literacy among SSA. It is widely suggested that raising the health literacy of the general population in the participating SSA countries is an effective approach to protect people from misinformation. Interventions to enhance compliance, and improve critical thinking and trust in science will be a promising avenue for future research. In addition to this, teaching the public health literacy, how to verify the source of information and other useful methods are necessary to combat misinformation. SSA countries will benefit from engaging NGOs for greater penetration to the grassroots and the countries could go even further and convince people, by providing accurate information in local languages. A valid quality criterion would be a strategy (or a combination of strategies) that ensures effective health communication to improve public knowledge of the infection or change health behaviour, and such intervention should be associated with a measurable effect on health outcomes.

References

-

Frenkel S, Alba D, Zhong R. Surge of virus misinformation stumps Facebook and Twitter. The New York Times. 2020.

-

Russonello G. Afraid of Coronavirus? That Might Say Something About Your Politics. The New York Times. 2020.

-

Organization WH. Novel Coronavirus ( 2019-nCoV): situation report, 3. 2020.

-

Singh L, Bansal S, Bode L, Budak C, Chi G, Kawintiranon K, et al. A first look at COVID-19 information and misinformation sharing on Twitter. arXiv preprint arXiv:200313907. 2020.

-

Gupta L, Gasparyan AY, Misra DP, Agarwal V, Zimba O, Yessirkepov M. Information and misinformation on COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Korean medical science. 2020;35(27).

-

Jelnov P. Confronting Covid-19 myths: Morbidity and mortality. GLO Discussion Paper; 2020. https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/glodps/516.html

-

Sahoo S, Padhy SK, Ipsita J, Mehra A, Grover S. Demystifying the myths about COVID-19 infection and its societal importance. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020.

-

Massinga Loembé M, Tshangela A, Salyer SJ, Varma JK, Ouma AEO, Nkengasong JN. COVID-19 in Africa: the spread and response. Nature Medicine. 2020;26(7):999-1003.

-

Amgain K, Neupane S, Panthi L, Thapaliya P. Myths versus Truths regarding the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) Outbreak. Journal of Karnali Academy of Health Sciences. 2020;3(1).

-

Freeman D, Waite F, Rosebrock L, Petit A, Causier C, East A, et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychological Medicine. 2020:1-13.

-

Shamshina JL, Rogers RD. Are Myths and Preconceptions Preventing Us from Applying Ionic Liquid Forms of Antiviral Medicines to the Current Health Crisis? International journal of molecular sciences. 2020;21(17):6002.

-

Control CfD, Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019: COVID-19. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html

-

Carbone M, Green JB, Bucci EM, Lednicky JA. Coronaviruses: facts, myths, and hypotheses. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2020;15(5):675-8.

-

COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa [press release]. London: King’s Global Health Institute 2020. https://healthasset.org/daily-update-on-covid-19-in-sub-saharan-africa/

-

Organization WH. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): situation report, 182. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200720-covid-19-sitrep-182.pdf

-

Mennechet FJ, Dzomo GRT. Coping with COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa: what might the future hold? Virologica Sinica. 2020:1-10. doi:10.1007/s12250-020-00279-2

-

Global Health Workforce Statistics, OECD, supplemented by country data: Physicians (per 1,000 people) [Internet]. The World Bank Group. 2020. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS.

-

UN. COVID-19: Lockdown exit strategies for Africa. Addis Ababa: United Nations Economic Commission for Africa; 2020. https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210053945

-

Cram P, Fendrick AM, Inadomi J, Cowen ME, Carpenter D, Vijan S. The impact of a celebrity promotional campaign on the use of colon cancer screening: the Katie Couric effect. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163(13):1601-5.

-

Kim S, Koniak-Griffin D, Flaskerud JH, Guarnero PA. The impact of lay health advisors on cardiovascular health promotion: using a community-based participatory approach. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2004;19(3):192-9.

-

Kishore J, Gupta A, Jiloha RC, Bantman P. Myths, beliefs and perceptions about mental disorders and health-seeking behavior in Delhi, India. Indian journal of Psychiatry. 2011;53(4):324.

-

Higgs P, Sacks-Davis R, Gold J, Hellard M. Barriers to receiving hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs: Myths and evidence. Hepatitis Monthly. 2011;11(7):513.

-

Cameron KA, Roloff ME, Friesema EM, Brown T, Jovanovic BD, Hauber S, et al. Patient knowledge and recall of health information following exposure to “facts and myths” message format variations. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;92(3):381-7.

-

Pennycook G, McPhetres J, Zhang Y, Lu JG, Rand DG. Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychological science. 2020;31(7):770-80.

-

Ovenseri-Ogbomo G, Ishaya T, Osuagwu UL, Abu EK, Nwaeze O, Oloruntoba R, et al. Factors associated with the myth about 5G network during COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Global Health Reports. 2020;4:1-13.

-

WHO. Coronavirus. In: Organization WH, editor. Geneva 2020. https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1

-

Nadler JT, Weston R, Voyles EC. Stuck in the Middle: The Use and Interpretation of Mid-Points in Items on Questionnaires. The Journal of General Psychology. 2015;142(2):71-89.

-

Palmieri L, Vanacore N, Donfrancesco C, Lo Noce C, Canevelli M, Punzo O, et al. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized individuals dying with COVID-19 by age group in Italy. 2020;75(9):1796-800.

-

Ohlheiser A. Older users share more misinformation. Your guess why might be wrong. MIT Technology Review. 2020 May 26;Sect. Humans and technology.

-

Stanley M, Seli P, Barr N, Peters K. Analytic-thinking predicts hoax beliefs and helping behaviors in response to the covid-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/m3vth

-

Roozenbeek J, Schneider CR, Dryhurst S, Kerr J, Freeman AL, Recchia G, et al. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. 2020;7(10):201199.

-

Bastani P, Bahrami MAJJomIr. COVID-19 Related Misinformation on Social Media: A Qualitative Study from Iran. 2020. doi:10.2196/18932

-

Abedi V, Olulana O, Avula V, Chaudhary D, Khan A, Shahjouei S, et al. Racial, economic, and health inequality and COVID-19 infection in the United States. 2020:1-11. doi: 10-1007/s40615-020-00833-4

-

Gyasi RM. COVID-19 and mental health of older Africans: an urgency for public health policy and response strategy. International Psychogeriatrics. 2020;32(10):1187-92.

-

Porat T, Nyrup R, Calvo RA, Paudyal P, Ford E. Public Health and Risk Communication During COVID-19—Enhancing Psychological Needs to Promote Sustainable Behavior Change. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020;8(637).

-

Nakkazi E. Obstacles to COVID-19 control in east Africa. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(6):660.

-

Jakubu MG. Media Information Literacy. Nairobi, Kenya: Centre for media & information literacy; 2019 25 August. https://medialiteracy-kenya.info/now-is-the-time-for-global-and-local-adaptation-of-media-and-information-literacy-initiatives/

-

Roberts M, Callahan L, O’Leary C. Social media: A path to health literacy. Information Services & Use. 2017;37(2):177-87.

-

Kraemer MU, Yang C-H, Gutierrez B, Wu C-H, Klein B, Pigott DM, et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. 2020;368(6490):493-7. doi:10.1101/2020.03.02.20026708

-

Moehler DC, Singh N. Whose News Do You Trust? Explaining Trust in Private versus Public Media in Africa. Political Research Quarterly. 2009;64(2):276-92.

-

Islam MS, Sarkar T, Khan SH, Kamal A-HM, Hasan SM, Kabir A, et al. COVID-19–related infodemic and its impact on public health: A global social media analysis. 2020;103(4):1621-9.

-

Uscinski JE, Enders AM, Klofstad C, Seelig M, Funchion J, Everett C, et al. Why do people believe COVID-19 conspiracy theories? Harvard Kennedy Sch Misinf Rev. 2020;1(3). doi:10.37016/mr-2020-015

-

Pickles K, Cvejic E, Nickel B, Copp T, Bonner C, Leask J, et al. COVID-19: Beliefs in misinformation in the Australian community. medRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.08.04.20168583

-

Hjort J, Poulsen J. The arrival of fast internet and employment in Africa. American Economic Review. 2019;109(3):1032-79.

-

Fricker RD. Sampling methods for online surveys. The SAGE handbook of online research methods. 2016:184-202.

-

Effenberger M, Kronbichler A, Shin JI, Mayer G, Tilg H, Perco P. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic with Internet Search Volumes: A Google TrendsTM Analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;95:192-7.

-

Eysenbach G. Infodemiology: The epidemiology of (mis) information. The American Journal of Medicine. 2002;113(9):763-5.