Version of Record (VoR)

Abu, E. K., Oloruntoba, R., Osuagwu, U. L., Bhattarai, D., Miner, C. A., Goson, P. C., … Agho, K. E. (2021). Risk perception of COVID-19 among sub-Sahara Africans : a web-based comparative survey of local and diaspora residents. Bmc Public Health, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11600-3

Risk Perception of COVID-19 among Sub-Sahara Africans:

A Web-based Comparative Survey of Local and Diaspora Residents

Title page

Emmanuel Kwasi Abu, PhD[1], Richard Oloruntoba, PhD[2], Uchechukwu Levi Osuagwu, PhD[3,13]*, Dipesh Bhattarai[4], Chundung Asabe Miner FWACP [5], Piwuna Christopher Goson, MSc[6], Raymond Langsi, MBBS[7], Obinna Nwaeze, MSc DM[8], Timothy G Chikasirimobi, MSc[9], Godwin O Ovenseri-Ogbomo, PhD [10,13], Bernadine N Ekpenyong, PhD [11,13], Deborah Donald Charwe, MSc[12], Khathutshelo Percy Mashige, PhD[13], Tanko Ishaya, PhD[14], Kingsley Emwinyore Agho, PhD [15,13]

Affiliations:

[1] Senior Lecturer, Department of Optometry and Vision Science, School of Allied Health Sciences, University of Cape Coast, 00233, Ghana; email: eabu@ucc.edu.gh

[2] Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management and Discipline Leader (Supply Chain Management), Curtin Business School, School of Management and Marketing, Curtin University, Bentley, WA 6151, Australia; email: Richard.Oloruntoba@curtin.edu.au

[3] Research Fellow, Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism Translational Research Unit, Western Sydney University, Campbelltown, NSW 2560, Australia*; email: l.osuagwu@westernsydney.edu.au

[4] Lecturer, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, Victoria Australia. dipeshbhattarai@hotmail.com

[5] Associate Professor, Department of Community Medicine, College of Health Sciences, University of Jos, Jos 930003, Nigeria. Email: minerc@unijos.edu.ng

[6] Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, College of Health Sciences, University of Jos, Nigeria; Email: piwunag@unijos.edu.ng

[7] Head of Health Division, University of Bamenda Bambili, Cameroon; email: info@uniba.cm

[8] Practising Physician, County Durham and Darlington National Health Service (NHS) Foundation. DL3 0PD United Kingdom; email: o.nwaeze@nhs.net

[9] Masters Candidate, Department of Optometry and Vision Sciences, School of Public Health, Biomedical Sciences and Technology, Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kakamega 50100 Kenya; email: chikasirimobi@gmail.com

[10] Assistant Professor, Department of Optometry, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Qassim University, Saudi Arabia; Department of Optometry, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City 300283, Nigeria; email: godwin.ovenseri-ogbomo@uniben.edu

[11] Head, Department of Public Health, Faculty of Allied Medical Sciences, College of Medical Sciences, University of Calabar, Cross River State, 540271; email: bekpenyong@unical.edu.ng

[12] Senior Research Nutritionist, Tanzania Food and Nutrition Center, Dar-es Salaam P. O. Box 977 Tanzania; email: mischarwe@yahoo.co.uk

[13] Professor of Optometry, School of Health Sciences, African Vision Research Institute (AVRI), University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville Campus, Durban, 3629, South Africa; email: mashigek@ukzn.ac.za

[14] Professor of Computer Science, Department of Computer Science, University of Jos, Jos 930003, Nigeria; email: ishayat@unijos.edu.ng

[15]Associate Professor in Biostatistics, School of Health Sciences, Western Sydney University, Campbelltown, NSW 2560, Australia. African Eye and Public Health Research Initiative; email: K.Agho@westernsydney.edu.au

*Correspondence: Dr Uchechukwu Levi Osuagwu

Postal Address: Level 2, Rm X.08, MacArthur Clinical School building, Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism Translational Research Unit, Western Sydney University, Campbelltown, NSW 2560, Australia.

email: l.osuagwu@westernsydney.edu.au Tel.: +61401193234

Abstract

Background: Perceived risk towards the coronavirus pandemic is key to improved compliance with public health measures to reduce the infection rates. This study investigated how Sub-Saharan Africans (SSA) living in their respective countries and those in the diaspora perceive their risk of getting infected by the COVID-19 virus and associated factors.

Methods: A web-based cross-sectional survey on 1969 participants aged 18 years and above (55.1% male) was conducted between April 27th and May 17th 2020. The dependent variable was the perception of risk for contracting COVID-19 scores. Independent variables included demographic characteristics, and COVID-19 related knowledge and attitude scores. Univariate and multiple linear regression analyses identified the factors associated with risk perception towards COVID-19.

Results: Among the respondents, majority were living in SSA (n=1855, 92.8%) and 143 (7.2%) in the diaspora. There was no significant difference in the mean risk perception scores between the two groups (p=0.117), however, those aged 18-28 years had lower risk perception scores (p = 0.003) than the older respondents, while those who were employed (p = 0.040) and had higher levels of education (p < 0.001) had significantly higher risk perception scores than other respondents. After adjusting for covariates, multivariable analyses revealed that SSA residents aged 39-48 years (adjusted coefficient, β = 0.06, 95% CI [0.01, 1.19]) and health care sector workers (β = 0.61, 95% CI [0.09, 1.14]) reported a higher perceived risk of COVID-19. Knowledge and attitude scores increased as perceived risk for COVID-19 increased for both SSAs in Africa (β = 1.19, 95% CI [1.05, 1.34] for knowledge; β = 0.63, 95% CI [0.58, 0.69] for attitude) and in Diaspora (β = 1.97, 95% CI [1.16, 2.41] for knowledge; β = 0.30, 95% CI [0.02, 0.58] for attitude).

Conclusions: There is a need to promote preventive measures focusing on increasing people’s knowledge about COVID-19 and encouraging positive attitudes towards the mitigation measures such as vaccines and education. Such interventions should target the younger population, less educated and non-healthcare workers.

Keywords: Africa, pandemic, diaspora, lockdown, risk perception, Sub-Sahara Africa, knowledge, COVID-19.

Introduction

Risk perception refers to people’s subjective assessments of the possibility of outcomes that may follow undesirable events such as disasters and pandemics[1]. The ongoing novel coronavirus SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused enormous global mortality and public health devastation[2]. While the 2014 West African Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) pandemic was limited to African countries, and the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) of 2002–03 limited to Asian countries, COVID-19 has been a global and unprecedented ‘black swan’ event [3, 4]. COVID-19 infection is highly contagious, and mortality caused by the virus has exceeded 3.4 million deaths as of 27th of May 2021 ─ more than any of its predecessors[5]. It is, therefore no surprise that countries are in a race towards developing and administering an effective vaccine[6, 7].

In response to the COVID-19 global threat[8], the World Health Organization (WHO) immediately raised awareness of healthcare workers around the world[9]. The WHO has also raised funds globally and developed Strategic Preparedness and Response Plans (SPRP) to support and protect poorer countries with weak healthcare systems[10]. The goal of the SPRP was to control infection, limit transmission, communicate key information, provide early acute care, and minimize disastrous economic and social effects. National governments locked down their populations, stopped the mobility of goods and services, closed all schools and universities, and shut all state and international borders with many employees working from homes [11-14]. Nonetheless, these mitigating measures’ success depends upon the public’s readiness to comply, which in turn is inspired by their risk perceptions about the pandemic[15].

Globally, devastating pandemics such as COVID-19 can provide valuable opportunities to learn about human risk perception and attendant behavior[16, 17] and how findings from such studies can be used to inform the allocation of resources within such countries and within international multilateral organizations and agencies such as the WHO[18, 19]. Such studies can also provide an evidence base for the formulation of public health and risk policies. Severe outcomes from natural disasters are often influenced by the level and distribution of economic resources and income within the population of a country (or region)[20, 21]. Several seminal bodies of literature highlight the role of resources or the lack of them in societal responses to disasters[22] and show how positive psychology can contribute to community development during disasters[23]. Culture and risk perception are closely linked and cultural beliefs and values may contribute to the success or otherwise of efforts to control the COVID 19 pandemic[24, 25]. As a result of the different cultural exposures of African residents and Africans living in the diaspora (living outside Africa), this comparative analysis will bring to the fore what specific local context risk management strategies should be implemented by SSA governments. For instance, Quinn et al. showed that people’s attachment to their place of residence affected their perceived disaster-related risks [26]. The findings of this web-based cross-sectional study will highlight the implications of the analysis for what we might expect of Africans living in Africa and Africans living outside Africa as well as policy implications in disaster risk management in general. For policymakers tasked with communicating risk, this research would provide a particularly valuable lens through which we can address the emotional underpinnings of adaptation behavior.

Methods

Design and setting of the study

This was an online survey created in Survey monkey to assess the risk perceptions of Africans. The study was conducted between April 27th and May 17th 2020 corresponding to the mandatory lockdown period in most SSA countries. The survey instrument shown in the Supplementary Table, was adapted and developed from the WHO recommended questions [27] and have been used in previous studies[27]. It was not feasible to undertake a conventional Africa-wide community-based sampling survey at this particular period of lockdown and restricted mobility. A one-page project information statement, which doubled as a recruitment poster, was posted/reposted to WhatsApp and Facebook chat groups and individual accounts together with an e-Link to the online survey. The information sheet and poster contained a brief introduction on the background of the study, its objectives, procedures, the voluntary nature of participation, the declaration of anonymity, privacy and confidentiality, as well as instructions for completing the questionnaire.

We also posted the poster and questionnaire on various websites and official accounts of several local organisations and individuals. Survey questionnaires were also sent out by email to selected groups and individuals in all the target countries, relying on the authors’ networks with collaborating academics and local people.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was divided into three sections, including demographics, knowledge, risk perception, feeling about self-isolation, attitude towards public health practices to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 (compliance) as presented in Table 1. Most of the items on the questionnaire that assessed the respondent’s knowledge of COVID- 19, required mostly a ‘true’ or ‘false’ or a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response with an additional “Not sure” option. Each question used a binary scale, and a correct answer was assigned 1 point, whereas an incorrect/unsure answer was assigned 0 points. The knowledge score ranged from 0–18 points. These items have been validated elsewhere to have an acceptable internal consistency[28]. To reduce unintended bias, we conducted a statistical test using Kuder Richardson correlation coefficient for binary outcomes by creating two dummy variables. One of the dummy variables included ‘Yes’ and ‘Not sure’ and the other dummy variable was the combination of ‘No’ and ‘Unsure’ and the alpha coefficient for the two dummy variables was 0.86, indicating a strong relationship.

Table 1. Survey items for knowledge, attitude and perception towards COVID-19.

| Knowledge | |

| K1 | Are you aware of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak? |

| K2 | Are you aware of the origin of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak? |

| K3 | Do you think Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak is dangerous? |

| K5 | Do you think Hand Hygiene / Hand cleaning is important to control the spread of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak? |

| K6 | Do you think ordinary residents can wear general medical masks to prevent the infection by the COVID-19 virus? |

| K7 | Do you think there are any specific medicines to treat Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)? |

| K8 | The main clinical symptoms of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) are: Fever, Fatigue, dry cough, sore throat |

| K9 | Unlike the common cold, stuffy nose, runny nose, and sneezing are less common in persons infected with the COVID-19 virus. |

| K10 | There currently is no effective cure for COVID-2019, but early symptomatic and supportive treatment can help most patients recover from the infection |

| K11 | It is not necessary for children and young adults to take measures to prevent the infection by the COVID-19 virus |

| K12 | COVID-19 individuals cannot spread the virus to anyone if there’s no fever |

| K13 | The COVID-19 virus spreads via respiratory droplets of infected individuals |

| K14 | To prevent getting infected by Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), individuals should avoid going to crowded places such as train stations, religious gatherings, and avoid taking public transportation |

| K15 | Isolation and treatment of people who are infected with the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) virus are effective ways to reduce the spread of the virus. The observation period is usually 14 days |

| K16 | Not all persons with COVID-2019 will develop to severe cases. Only those who are elderly, have chronic illnesses, and are obese are more likely to be severe cases. |

| Risk Perception | |

| Please rate your chances of personal risk of infection with COVID-19 for each of the following? | |

| P1 | Risk of becoming infected. |

| P2 | Risk of becoming severely infected |

| P3 | Risk of dying from the infection |

| P4 | How much worried are you because of COVID-19? |

| P5 | How likely do you think Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) will continue in your country? |

| P6 | If Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues in your country, how concerned would you be that you or your family would be directly affected? |

| How do you feel about the Self-isolation? | |

| P7 | I am worried about self-isolation. |

| P8 | I am bored by self-isolation. |

| P9 | I am frustrated by self-isolation |

| P10 | I am angry because of self-isolation. |

| P11 | I am anxious about self-isolation. |

| P12 | I am angry because of the quarantine. |

| Attitude towards public health practices to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 (Compliance) | |

| A1 | Are you currently or have you been in (domestic/home) quarantine because of COVID-19? |

| A2 | Are you currently or have you been in self-isolation because of COVID-19? |

| A3 | In recent days, have you gone to any crowded place including religious events? |

| A4 | In recent days, have you worn a mask when leaving home? |

| A5 | In recent days, have you been washing your hands with soap and running water for at least 20 seconds each time? |

| A6 | Since the government gave the directives on preventing getting infected, have you procured your mask and possibly sanitizer? |

| A7 | Have you travelled outside your home in recent days using the public transport |

| A8 | Are you encouraging others that you meet to observe the basic prevention strategies suggested by the authorities? |

| See Supplementary Table for the full survey item with the response options | |

Characteristics of the participants

Participants were those living in South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and Malawi. Respondents in the diaspora, including those living in the UK, USA, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Germany, were also included. Recipients were further encouraged to send on or ‘snowball’ the survey questionnaire to other WhatsApp groups that they know as well as to friends. Eligibility criteria included that respondents had to be of African nationality, aged 18 years or older, able to understand the contents of the poster/questionnaire, and agreed to participate in the study.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable for this study was the perception of risk for contracting COVID-19, which was categorized as continuous. The items utilized to measure the risk perception of COVID-19 are shown in Table 1 (P1-P6). The responses included very high, high, low, very low, and unlikely. The items ranged from 1 (unlikely) to 5 (very high).

Independent variables

These included demographic A) characteristics of the participants, which consists of age, gender, marital status, education, employment status, occupation (if employed), religion, if they lived alone, the number of people living together in the household and place of current residence. B), Knowledge about COVID-19 origin, symptoms and prevention. C), Feeling about the practice of self-isolation during COVID-19 lockdown. D) Attitude towards COVID-19 mitigation measures that included the practice of self-isolation, home quarantine (A1 and A2) as well as compliance questions (A3-A8)(see Table 1).

Sample size determination

The survey assumed a proportion of 50% with 95% confidence and 2.5% margin of error was based on a previous study[29]. This is because the main objective of this research was on COVID-19, and there are no previous studies from SSA that examined factors associated with risk perception of 2019-nCoV. An online sample size calculator was used, and we assumed a sample size of approximately 1921, including 20% non-response rate.

Statistical analysis

Scores for risk perception were calculated for each of the independent variables and treated as a continuous variable with mean (±standard deviation) risk scores. The risk perception scores ranged from 1 to 30. Risk scores by independent variables were summarized using a t-test for two categorical groups and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for more than two categorical groups. Univariate linear regression analyses were conducted to assess the unadjusted coefficients (B) with 95% confidence intervals among SSA residents and residents in the diaspora. The adjusted coefficients (β) with 95% confidence intervals obtained from the multiple linear regression model were used to measure the factors associated with the risk perception of COVID-19 among SSA residents and those in the diaspora. Only significant variables in the univariate analysis were used to build the regression model. Knowledge was included in the model because it is strongly related to attitude and practice, while knowledge and attitude have been reported to be associated with practice ([30]). Feeling about the practice of self-isolation during COVID-19 lockdown would help in identifying individuals who could develop mental health issue during the lockdown because past studies showed that longer duration of separation and restriction of people’s movement due to SARS were associated with poorer mental health[31, 32]. Including attitude towards the mitigation practices in the model would influence action to reduce the spread of the infection. In our linear regression analyses, we checked for homogeneity of variance and multicollinearity, including Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) and the VIF < 4 was considered suitable [33]. All analysis was performed using Stata version 14.1 (Stata Corp. College Station United States of America), and a two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics of respondents in Africa and in the diaspora

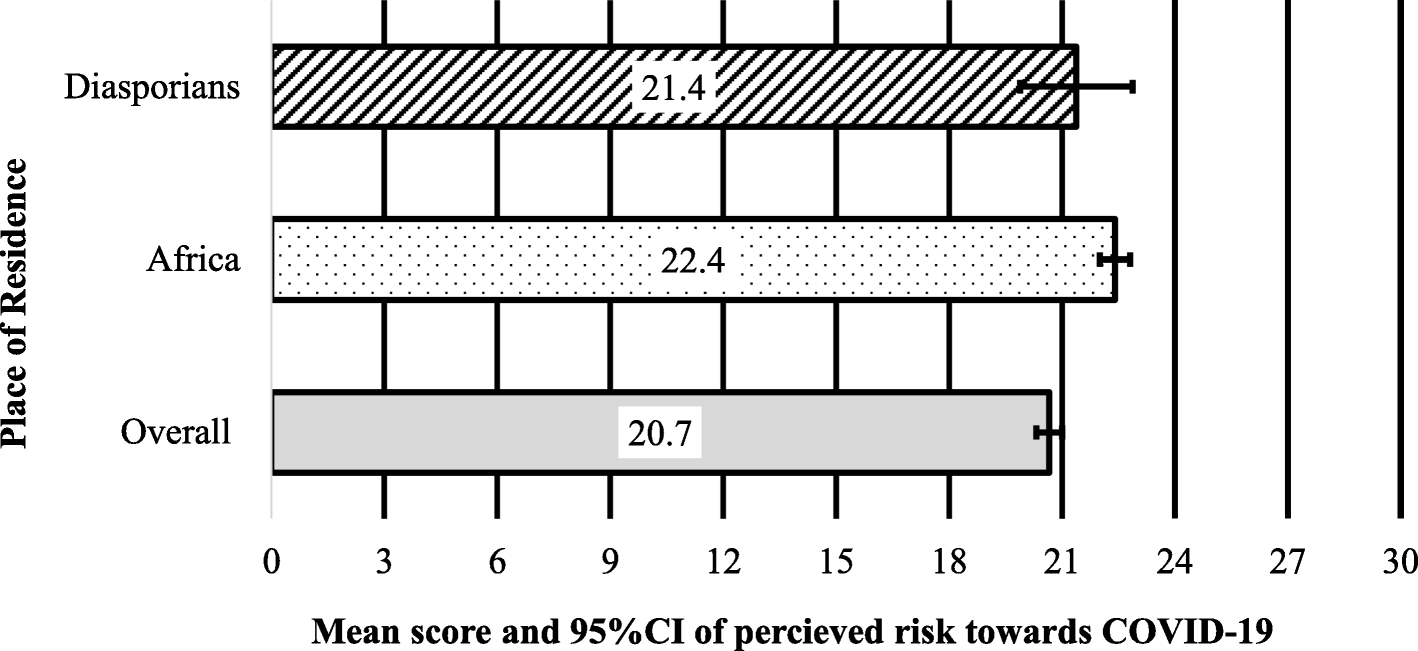

Of 1,969 respondents (55.1% male and 44.9% female) that completed the survey, the majority were living in SSA (n=1855, 92.8%) and 143 (7.2%) in the diaspora at the time of data collection. The percentage distribution of the respondents by country of residence for local residents and those in Diaspora has been presented as a Supplementary figure. The majority of the local respondents lived in Ghana (28.2%), Nigeria (26.7%) and South Africa (21.7%), while many of those in diaspora were from the USA (19.6%), UK (18.2%) and Australia (15.4%). Figure 1 presents the mean scores (out of 30) and the 95% CI of risk perception scores towards COVID-19 based on respondents region of residence. There was no significant difference in the mean risk perception scores between the two groups (p=0.117). Table 2 shows the demographics of SSA in Africa and in the diaspora with their mean (standard deviation) scores for perceived risk towards COVID-19. Compared to SSA residents, those living in the diaspora were younger, more often female, and less often married.

Figure 1. Mean scores (/30) of risk perception towards COVID-19 among Sub-Saharan Africans living locally (Africa) and in the diaspora. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals of mean scores

Table 2. Demographics of Sub-Saharan Africans living in Africa and in the diaspora with their mean (standard deviation) scores for the perceived risk of contracting COVID-19.

| Variables | Local SSA |

Scores | P-value | Diaspora SSA |

Scores | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | ||||||

| Age category in years, n = 1818(b) | ||||||

| 18–28 | 722 | 20.0 (8.1) | 0.003 | 52 | 20.7 (8.1) | 0.371 |

| 29–38 | 476 | 21.3 (7.3) | 47 | 20.2 (7.5) | ||

| 39–48 | 393 | 21.3 (7.7) | 31 | 18.3 (8.9) | ||

| 49+ | 227 | 21.6 (7.1) | 13 | 22.5 (5.6) | ||

| Sex, n = 1822 | ||||||

| Males | 1002 | 21.0 (7.6) | 0.394 | 80 | 21.0 (7.0) | 0.118 |

| Females | 820 | 20.7 (7.9) | 62 | 18.9 (8.8) | ||

| Marital status, n = 1825 | ||||||

| Married | 793 | 21.1 (7.4) | 0.293 | 70 | 20.1 (8.2) | 0.929 |

| Not married (a) | 1032 | 20.7 (8.0) | 73 | 20.2 (7.7) | ||

| Education status, n = 1827 (b) | ||||||

| Postgraduate education (Masters /PhD) |

576 | 21.3 (6.8) | < 0.001 | 56 | 20.4 (7.7) | 0.918 |

| Bachelor education | 861 | 21.1 (7.8) | 64 | 20.1 (8.2) | ||

| Secondary/Primary education |

390 | 19.1 (9.0) | 23 | 19.5 (7.2) | ||

| Employment status, n = 1830 | ||||||

| Employed | 1200 | 21.1 (7.5) | 0.04 | 97 | 19.8 (7.7) | 0.462 |

| Not employed | 630 | 20.3 (8.2) | 46 | 20.9 (8.3) | ||

| Religion, n = 1825 | ||||||

| Christianity | 1605 | 20.8 (7.7) | 0.510 | 136 | 20.2 (7.8) | 0.802 |

| Others | 220 | 21.2 (7.6) | 7 | 19.4 (9.6) | ||

| Occupation, 1753 | ||||||

| Non-health care sector | 1357 | 20.6 (7.8) | 0.109 | 111 | 19.6 (8.1) | 0.743 |

| Health care sector | 396 | 21.3 (7.8) | 34 | 20.2 (8.9) | ||

| Household factors | ||||||

| Do you live alone during COVID-19, n = 1826 | ||||||

| No | 1483 | 20.8 (7.6) | 0.864 | 117 | 20.0 (7.8) | 0.86 |

| Yes | 343 | 20.9 (8.1) | 26 | 20.3 (8.6) | ||

| Number living together, n = 1650 (b) | ||||||

| 1–3 people | 466 | 20.9 (7.5) | 0.866 | 36 | 18.9 (8.9) | 0.249 |

| 4–6 people | 870 | 20.7 (7.9) | 37 | 17.5 (10.2) | ||

| 6+ people | 314 | 21.0 (7.7) | 26 | 21.3 (6.4) | ||

| Public Attitude towards mitigation measures | ||||||

| Practiced self-isolation, n = 1644 | ||||||

| No | 1141 | 22.8 (4.7) | 0.390 | 83 | 21.9 (5.3) | 0.871 |

| Yes | 503 | 23.0 (5.1) | 50 | 21.8 (5.7) | ||

| Practiced home quarantine, n = 1641 | ||||||

| No | 989 | 22.8 (4.7) | 0.814 | 91 | 21.7 (5.3) | 0.496 |

| Yes | 652 | 22.9 (4.9) | 42 | 22.4 (5.9) | ||

| Feeling about the self-isolation | ||||||

| Anxious, n = 1463 | ||||||

| No | 592 | 20.8 (7.7) | 0.865 | 50 | 21.0 (6.8) | 0.213 |

| Yes | 871 | 20.7 (8.1) | 62 | 19.0 (9.4) | ||

| Bored, n = 1493 | ||||||

| No | 444 | 20.7 (7.9) | 0.990 | 30 | 19.9 (8.1) | 0.897 |

| Yes | 1049 | 20.7 (7.9) | 87 | 20.1 (8.3) | ||

| Frustrated, n = 1467 | ||||||

| No | 704 | 20.7 (7.8) | 0.982 | 63 | 20.5 (8.4) | 0.657 |

| Yes | 763 | 20.7 (8.2) | 56 | 18.4 (8.2) | ||

| Angry, n = 1418 | ||||||

| No | 1098 | 20.8 (8.0) | 0.692 | 88 | 22.4 (9.5) | 0.283 |

| Yes | 320 | 20.6 (7.8) | 23 | 19.7 (9.2) | ||

| Knowledge scores (c) | 1855 | 7.2 (2.2) | 150 | 7.2 (2.5) | ||

| Attitude scores | 1855 | 13.7 (5.2) | 150 | 14.0 (5.5) | ||

| Abbreviation: COVID-19 Coronavirus diseases 2019 For each variable, no of responses = 1969 otherwise indicated P-values are results of independent t-test and analysis of variance (a) single, divorced and widowed (b) Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used (c) continuous variables |

||||||

Perception of overall COVID-19-associated risk

For those in SSA, the risk perception score was significantly lower in the 18-28 years age group (p = 0.003, Table 2) than in older age groups. Again, employment (p = 0.040) and a higher level of education (p < 0.001, Table 2) had significantly higher risk perception scores than being unemployed with lower education, respectively. There was no significant difference in the risk perception scores based on gender, marital status, religion, occupation, and the number of people living together among SSA residents. The risk perception score did not significantly differ in sociodemographic characteristics among participants living in the diaspora.

Among those living in SSA and those in the diaspora, the mean scores for risk perception was similar between those who either practiced or did not practice self-isolation and home quarantine. Similarly, no significant differences in risk perception were observed between participants who reported being anxious, bored, frustrated, angry compared to those who did not report any of these symptoms in the two groups.Table 3 shows the unadjusted and adjusted coefficients for factors associated with risk perception of COVID-19 among Africans residing in SSA. In contrast, Table 4 shows the same information for those living in the diaspora. Table 3 shows that among the local SSA residents, working in the health care sector (adjusted coefficient, β = 0.61, 95% CI [0.09, 1.14]) was associated with high-risk perception towards COVID-19, as well as knowledge (β = 1.19, 95% CI [1.05, 1.34]) and attitude (β = 0.63, 95% CI [0.58, 0.69]) towards COVID-19 mitigation measures. Although, unemployment (B = -0.78, 95% CI [-5.53, -0.04]) and lower levels of education (primary/secondary education, B = -2.19, 95% CI [-3.32, -1.05]) were associated with lower risk perception towards COVID-19 in the univariate analysis, the significance was lost after adjusting for other potential cofounder factors.From Table 3, it can be seen that, among SSAs in the diaspora, knowledge (β = 1.79, 95% CI [1.16, 2.41]) and attitude (β = 0.30, 95% CI [0.02, 0.58]) were similarly associated with a high-risk perception of COVID-19. However, there was no significant association between the demographic variables and the risk perception scores in this group.

Table 3. Unadjusted and adjusted coefficients for factors associated with perceived risk of contracting Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) among SSAs living in African countries.

| Variables | Unadjusted Coefficient |

95%CI | Adjusted Coefficient |

95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | ||||

| Age category in years | ||||

| 18-28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 29-38 | 1.29 | 0.40, 2.18 | 0.49 | -0.06, 1.05 |

| 39-48 | 1.30 | 0.35, 2.24 | 0.60 | 0.01, 1.19 |

| 49+ | 1.59 | 0.44, 2.73 | 0.29 | -0.43, 1.01 |

| Sex | ||||

| Males | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Females | -0.31 | -1.02, 0.40 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Not married | -0.38 | -1.10, 0.33 | ||

| Education status | ||||

| Postgraduate education (Masters /PhD) |

0.00 | – | – | |

| Bachelor education | -0.20 | -0.98, 0.59 | ||

| Secondary/ Primary education |

-2.19 | -3.32, -1.05 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Not employed | -0.78 | -1.53, -0.04 | ||

| Religion | ||||

| Christianity | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Others | 0.37 | -0.72, 1.45 | ||

| Occupation | – | – | ||

| Non-health care sector | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Health care sector | 0.71 | -0.16, 1.59 | 0.61 | 0.09, 1.14 |

| Household factors | ||||

| Do you live alone during COVID-19 | ||||

| No | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Yes | 0.08 | -0.83, 0.99 | ||

| Number living together | ||||

| <3 people | 0.00 | – | – | |

| 4-6 people | -0.17 | -1.05, 0.70 | ||

| 6+ people | 0.07 | -1.04, 1.18 | ||

| Public Attitude towards COVID-19 Mitigation measures | ||||

| Practiced self-isolation | ||||

| No | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Yes | 0.22 | -0.28, 0.72 | ||

| Practiced home quarantine | ||||

| No | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Yes | 0.06 | -0.42, 0.53 | ||

| Feeling about the self-isolation | ||||

| Anxious | ||||

| No | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Yes | -0.07 | -0.90, 0.76 | ||

| Bored | ||||

| No | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Yes | 0.01 | -0.87, 0.88 | ||

| Frustrated | ||||

| No | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Yes | -0.01 | -0.83, 0.81 | ||

| Angry | ||||

| No | 0.00 | – | – | |

| Yes | -0.20 | -1.19, 0.79 | ||

| Knowledge score‡ | 2.38 | 2.26, 2.50 | 1.19 | 1.05, 1.34 |

| Attitude score‡ | 1.08 | 1.08, 1.13 | 0.63 | 0.58, 0.69 |

| Coronavirus diseases 2019, COVID-19. ‡=continuous variables. Confidence intervals (CIs) not including 0 are significant variables, |

||||

Table 4. Unadjusted and adjusted coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of factors associated with perceived risk of contracting Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) among SSAs living in the diaspora.

| Variables | Unadjusted Coefficent |

95% CI | Adjusted Coefficient |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | ||||

| Age category in years | ||||

| 18-28 | 0.00 | - | - | |

| 29-38 | -0.54 | -3.68, 2.60 | ||

| 39-48 | -2.45 | -6.00, 1.09 | ||

| 49+ | 1.75 | -3.09, 6.59 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Males | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Females | -2.08 | -4.70, 0.53 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Not married | 0.12 | -2.50, 2.74 | ||

| Education status | ||||

| Postgraduate Degree (Masters /PhD) | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Bachelor’s degree | -0.35 | -3.13, 2.44 | ||

| Secondary/Primary | -0.97 | -5.81, 3.87 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Unemployed | 1.04 | -1.76, 3.84 | ||

| Religion | ||||

| Christianity | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Others | -0.77 | -6.84, 5.30 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Non-health care sector | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Health care sector | 0.53 | -2.68, 3.75 | ||

| Household factors | ||||

| Do you live alone during COVID-19 | ||||

| No | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Yes | 0.30 | -3.09, 3.70 | ||

| Number living together | ||||

| <3 people | 0.00 | - | - | |

| 4-6 people | -1.43 | -5.55, 2.70 | ||

| 6+ people | 2.38 | -2.15, 6.92 | ||

| Public Attitude towards COVID-19 mitigation measures | ||||

| Self-isolation | ||||

| No | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Yes | -0.16 | -2.10, 1.78 | ||

| Home quarantined | ||||

| No | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Yes | 0.70 | -1.32, 2.72 | ||

| Feeling about the self-isolation | ||||

| Anxious | ||||

| No | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Yes | -1.98 | -5.13, 1.16 | ||

| Bored | ||||

| No | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Yes | 0.23 | -3.22, 3.67 | ||

| Frustrated | ||||

| No | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Yes | -0.67 | -3.65, 2.31 | ||

| Angry | ||||

| No | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Yes | -2.11 | -5.98, 1.77 | 0.00 | |

| Knowledge score‡ | 2.36 | 1.97, 2.75 | 1.79 | 1.16, 2.41 |

| Attitude score‡ | 0.99 | 0.81, 1.17 | 0.30 | 0.02, 0.58 |

| Coronavirus diseases 2019, COVID-19. ‡=continuous variables. Confidence intervals (CIs) not including 0 are significant variables, |

||||

From Table 4, it can be seen that, among SSAs in the diaspora, knowledge (β = 1.79, 95% CI [1.16, 2.41]) and attitude (β = 0.30, 95% CI [0.02, 0.58]) were similarly associated with a high-risk perception of COVID-19. However, there was no significant association between the demographic variables and the risk perception scores in this group.

Discussion

This study found comparable high-risk perception scores among residents living in SSA and those in the diaspora, which were associated with an increase in knowledge of COVID-19 and attitude towards the mitigation measures. Health care workers resident in SSA had higher risk perception scores compared to their counterpart non-healthcare workers. Although having lower education and not working during the pandemic was associated with significantly lower risk perception of COVID-19 among local residents, this was nullified after adjusting for other demographic variables.

The finding that older individuals felt at greater risk of COVID-19 was in line with past studies showing that older individuals have significantly higher COVID-19 related severe complications and deaths than young individuals[34]. Public awareness of this information may explain the finding of lower risk perception for contracting the infection among younger respondents in SSA. As highlighted by Dillard et al[35], having a perceived low risk of infection can make young people become less compliant to public health measures. This can in turn lead to higher COVID-19 infection[35], and ultimately passing the infection to the population more susceptible to COVID-19 related complications since young people were shown to be more likely to transmit the virus than others[36]. In line with these findings, some countries took stringent steps to limit the young population from transmitting COVID-19 infection to the older population [37-40] but recorded mixed success[40-42]. Rapid and proactive outreach programs targeted at young people in Australia and Canada might explain why the risk perception was similar between younger and older participants living in the diaspora in this study[43]. Such directed programs and policies should be implemented within the vulnerable groups in our local populations.

Studies have reported a high perceived risk of COVID-19 among African health workers[44-46] but did not compare between health and non-health workers. In a cross-sectional study conducted on 350 Ghanaians during the early stage of the outbreak, there was no difference in risk perception scores between health and non-healthcare workers[47] but healthcare worker reported a higher mean scores than non-healthcare workers. The higher mean reported by healthcare worker in this study may be attributed to the fact that healthcare workers had to work even if their individual risk perception would want to make them to comply with risk mitigation such as isolation[48, 46]. In this study, high-risk perception for contracting COVID-19 was associated with working in the health sector, but this was only significant among those who were living in SSA. Firsthand experience with the virus is often linked to high-risk perception[49], higher knowledge of the disease among health care workers compared to the non-health workers might explain their higher perception of risk for contracting the infection. The lack of proper training on protective measures reported in previous studies by health workers in SSA countries[46] may explain the significant association found among local health care workers but not among those living in the diaspora. Again, the implementation of targeted policies may as well account for the lack of association among respondents living abroad.

In this study, knowledge about COVID-19 and a positive attitude towards the mitigation measures were associated with a high-risk perception of contracting the disease, both in SSA and the diaspora. Similar findings have been reported in Ethiopia[50], showing that individuals who perceive higher risk are more likely to adopt protective measures, which in turn influences the probability of infection[50, 51]. However, the prevalence of misinformation about COVID-19 among SSA respondents[52], together with the immoderate psychological stress caused by this misinformation about COVID-19 due to the poor knowledge about the disease[28], are potential sources of reduced risk perception in this sub region. These would lead to increased transmissions and mortality. Hence, accurate information about the pandemic using the trusted media platforms can help in accurate risk judgement and proper adoption of public health measures to control the spread of infection [28, 53].

COVID-19 related morbidity and mortality vary disproportionately based on sociodemographic characteristics, for instance, males and older people have high mortality due to COVID-19 compared to females and the young population[54]. Individual’s behaviours towards safety measures have been linked to their level of the perceived risk of disease[35]. Adopting public health measures such as the use of a nose mask in public areas and frequent hand sanitization can lead to successful control of air-borne infectious diseases like COVID-19[53]. Therefore, public health strategies for successful control of COVID-19 among SSAs may benefit from targeting the sub-population identified in this study. That is the unemployed, non-healthcare workers, the younger population and those with lower levels of education.

This study was limited by several factors: 1), assessed risk perception and comparing the perceptions from SSA residents in and outside Africa may be limited by the fact that those who felt they were at risk of COVID-19 infection were more likely to respond to recommended health behaviours [55]; 2), findings from this study cannot be generalizable to entire SSA regions; 3), it was an online survey made available only in English language thus restricting respondents without access to the internet where internet penetration remains relatively low and some from French-speaking SSA nations[56]. However, the use of an internet-based methodology was the only reliable means to disseminate information at the time of this study; 4), the survey items were self-administered and some of the questions for example, those on compliance require subjective responses, and has no answer that can be verified. If a respondent reported good behaviour but not practiced it, there is no way we can independently verify their response. Despite these limitations, this study from the SSA region provided insight into the role of residence in mitigating the factors that influence risk perception of COVID-19 among SSAs during the pandemic. The study used a robust analysis to control for potential confounders during the analysis in order to reduce the issue of bias.

Conclusions

In summary, this study explored the factors associated with the risk perception of contracting COVID-19 among SSAs, particularly looking at the role of residence in peoples’ level of risk perception. The findings indicate that health communication and education strategies designed to promote the adoption of preventive behaviours among SSAs should focus on increasing knowledge about the disease and encouraging a positive attitude towards the mitigation measures. In addition, such programmes will benefit from targeting the unemployed, less educated, healthcare workers and the younger population, for optimum outcome. These findings can be helpful in policy implications in disaster risk management, including infection control of COVID-19, particularly in English speaking countries in the SSA region.

List of abbreviations

COVID-19: coronavirus SARS-CoV2

SSA: Sub-Sahara Africa

CI: Confidence intervals

EVD: Ebola Virus Disease

EPPM: Extended parallel process model

WHO: World Health Organization

SPRP: Strategic Preparedness and Response Plans

ANOVA: Analysis of variance

Declaration

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Human Research Ethics Committee of the Cross River State Ministry of Health, Nigeria approved this study (#: CRSMOH/RP/REC/2020/116). Written informed consent was obtained from all respondents before participation, by asking respondents to voluntarily answer either a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the question inquiring whether they agreed to participate in the survey. Respondents could only proceed to complete the survey if they answered ‘yes’ to this question. All protocols are carried out in accordance in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration for Human Research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study

Authors’ contributions

K.E.A, U.L.O, R.O. conceptualized the study. K.E.A., E.K.A., B.N.E., K.P.M., P.C.G., U.L.O., G.O.O., O.N., R.O., T.I., T.C.G., D.D.C., C.A.M., R.L. and D.B. were involved in data collection and interpretation of the data. K.E.A., D.B. and U.L.O performed the formal analysis of the data. E.K.A., D.B., R.O. and U.L.O. drafted the original manuscript. K.E.A., G.O.O., E.K.A., B.N.E., K.P.M., P.C.G., O.N., R.O., T.I., T.C.G, D.D.C., C.A.M, R.L. and D.B. reviewed and edited the manuscript. K.E.A., T.I., D.D.C., K.P.M. and U.L.O. supervised the project.

Acknowledgement

Not Applicable

References

-

Paek H-J, Hove T. Risk perceptions and risk characteristics. Oxford research encyclopedia of communication; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.283. [Book] [Google Scholar]

-

Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10228):931–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [Article] [CAS] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Zito RR. Bounding the “Black Swan” Probability. In: Mathematical Foundations of System Safety Engineering. Tucson: Springer Charm; 2020. p. 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26241-9_3.

-

McMaster M, Nettleton C, Tom C, Xu B, Cao C, Qiao P. Risk management: rethinking fashion supply chain management for multinational corporations in light of the COVID-19 outbreak. J Risk Financ Manage. 2020;13(8):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13080173. [Article] [Google Scholar]

-

Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): Our world in data; 2020. url: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (cited on page 4). 2020.

-

Pereira M, Paixão E, Trajman A, De Souza RA, Da Natividade MS, Pescarini JM, et al. The need for fast-track, high-quality and low-cost studies about the role of the BCG vaccine in the fight against COVID-19. Respir Res. 2020;21:1–3. [Article] [Google Scholar]

-

Henley J, Connolly K, Jones S. European and US experts question UK’s fast-track of COVID vaccine: The Guardian. 4 December 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/03/europe-us-experts-question-uk-fast-track-covid-vaccine.

-

World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 73. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331686.

-

Ferioli M, Cisternino C, Leo V, Pisani L, Palange P, Nava S. Protecting healthcare workers from SARS-CoV-2 infection: practical indications. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(155):200068. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0068-2020. [Article] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Organization WH. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) strategic preparedness and response plan: Accelerating readiness in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: February 2020: World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. 2020. [Google Scholar]

-

Ogolodom MP, Mbaba AN, Alazigha N, Erondu OF, Egbe NO, Golden I, et al. Knowledge, Attitudes and Fears of HealthCare Workers towards the Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic in South-South, Nigeria. Health Sci J. 2020;2020(1):1–10 Sp Iss 1: 002. [Google Scholar]

-

Di Gennaro F, Pizzol D, Marotta C, Antunes M, Racalbuto V, Veronese N, et al. Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) current status and future perspectives: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082690.

-

Xiao Y, Torok ME. Taking the right measures to control COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):523–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30152-3. [Article] [CAS] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Law S, Leung AW, Xu C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): from causes to preventions in Hong Kong. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:156–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.059. [Article] [CAS] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Jahangiry L, Bakhtari F, Sohrabi Z, Reihani P, Samei S, Ponnet K, et al. Risk perception related to COVID-19 among the Iranian general population: an application of the extended parallel process model. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–8. [Article] [Google Scholar]

-

Brown P. Studying COVID-19 in light of critical approaches to risk and uncertainty: research pathways, conceptual tools, and some magic from Mary Douglas: Taylor & Francis; 2020.

-

Barnes SJ. Information management research and practice in the post-COVID-19 world. Int J Inf Manag. 2020;55:102175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102175. [Article] [Google Scholar]

-

Marron JM, Joffe S, Jagsi R, Spence RA, Hlubocky FJ. Ethics and resource scarcity: ASCO recommendations for the oncology community during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(19):2201–5. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.00960. [Article] [CAS] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

Farrell TW, Francis L, Brown T, Ferrante LE, Widera E, Rhodes R, et al. Rationing limited health care resources in the COVID-19 era and beyond: ethical considerations regarding older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(6):1143–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16539. [Article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

Tang R, Wu J, Ye M, Liu W. Impact of economic development levels and disaster types on the short-term macroeconomic consequences of natural Hazard-induced disasters in China. Int J Disaster Risk Sci. 2019;10(3):371–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-019-00234-0. [Article] [CAS] [Google Scholar]

-

De Juan A, Pierskalla J, Schwarz E. Natural disasters, aid distribution, and social conflict–Micro-level evidence from the 2015 earthquake in Nepal. World Dev. 2020;126:104715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104715. [Article] [Google Scholar]

-

Haeffele S, Storr VH, editors. Government Responses to Crisis: Mercatus Studies in Political and Social Economy. London: Springer Nature ; 2020. p. 1-145.

-

Morgado AM. Disasters, individuals, and communities: can positive psychology contribute to community development after disaster? Community Dev. 2020:1–14.

-

Appleby-Arnold S, Brockdorff N, Jakovljev I, Zdravković S. Applying cultural values to encourage disaster preparedness: lessons from a low-hazard country. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018;31:37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.04.015. [Article] [Google Scholar]

-

Rathod S. Rapid response: impact of culture on response to COVID 19. BMJ. 2020;369:m1556. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1556. [Article] [Google Scholar]

-

Quinn T, Bousquet F, Guerbois C, Sougrati E, Tabutaud M. The dynamic relationship between sense of place and risk perception in landscapes of mobility. Ecol Soc. 2018;23(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10004-230239.

-

Abir T, Kalimullah NA, Osuagwu UL, Yazdani DMN-A, Al Mamun A, Husain T et al. Factors associated with perception of risk and knowledge of contracting the novel COVID-19 among adults in Bangladesh: analysis of online surveys. 2020. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhong Y, Liu W, Lee T-Y, Zhao H, Ji J. Risk perception, knowledge, information sources and emotional states among COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Nurs Outlook. 2020;69(1):13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.08.005. [Article] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Abir T, Kalimullah NA, Osuagwu UL, Yazdani DMN-A, Mamun AA, Husain T, et al. Factors associated with the perception of risk and knowledge of contracting the SARS-Cov-2 among adults in Bangladesh: analysis of online surveys. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5252. [Article] [CAS] [Google Scholar]

-

Li Z-H, Zhang X-R, Zhong W-F, Song W-Q, Wang Z-H, Chen Q, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to coronavirus disease 2019 during the outbreak among workers in China: a large cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(9):e0008584. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008584. [Article] [CAS] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto,Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(7):1206–12. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1007.030703. [Article] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Reynolds DL, Garay J, Deamond S, Moran MK, Gold W, Styra R. Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136(7):997–1007. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268807009156. [Article] [CAS] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

Vatcheva KP, Lee M, McCormick JB, Rahbar MH. Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiol (Sunnyvale, Calif). 2016;6(2):227. [Google Scholar]

-

Drefahl S, Wallace M, Mussino E, Aradhya S, Kolk M, Brandén M, et al. A population-based cohort study of socio-demographic risk factors for COVID-19 deaths in Sweden. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5097. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18926-3. [Article] [CAS] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Dillard AJ, Ferrer RA, Welch JD. Associations between narrative transportation, risk perception and behaviour intentions following narrative messages about skin cancer. Psychol Health. 2018;33(5):573–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1380811. [Article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

Huang L, Zhang X, Zhang X, Wei Z, Zhang L, Xu J, et al. Rapid asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19 during the incubation period demonstrating strong infectivity in a cluster of youngsters aged 16-23 years outside Wuhan and characteristics of young patients with COVID-19: a prospective contact-tracing study. J Infect. 2020;80(6):e1–e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.006. [Article] [CAS] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Organization WH. COVID-19 global risk communication and community engagement strategy, December 2020–May 2021: interim guidance, 23 December 2020: World Health Organization; 2020.

-

Hasmuk K, Sallehuddin H, Tan MP, Cheah WK, Ibrahim R, Chai ST. The long term care COVID-19 situation in Malaysia. International Long-Term Care Policy Network; 2020. [Google Scholar]

-

Karim W, Haque A, Anis Z, Ulfy MA. The movement control order (mco) for covid-19 crisis and its impact on tourism and hospitality sector in Malaysia. Int Tour Hosp J. 2020;3:1–7. [Google Scholar]

-

Cousins S. Experts criticise Australia’s aged care failings over COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;396(10259):1322–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32206-6. [Article] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Hsu AT, Lane N, Sinha SK, Dunning J, Dhuper M, Kahiel Z. Impact of COVID-19 on residents of Canada’s long-term care homes–ongoing challenges and policy response. Int Long Term Care Policy Netw. 2020;17:1–8.

-

Mustaffa N, Lee S-Y, Mohd Nawi SN, Che Rahim MJ, Chee YC, Muhd Besari A, et al. COVID-19 in the elderly: A Malaysian perspective. J Glob Health. 2020;10:020370. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.020370. [Article] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

DDG/P Office and OECD. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on jobs and incomes in G20 economies. Saudi Arabia: International Labour Organization (ILO); 2020. p. 1-46.

-

Girma S, Agenagnew L, Beressa G, Tesfaye Y, Alenko A. Risk perception and precautionary health behavior toward COVID-19 among health professionals working in selected public university hospitals in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0241101. [Article] [CAS] [Google Scholar]

-

Abdel Wahed WY, Hefzy EM, Ahmed MI, Hamed NS. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and perception of health care workers regarding COVID-19, a cross-sectional study from Egypt. J Community Health. 2020;45(6):1242–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00882-0. [Article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

Ekpenyong B, Obinwanne CJ, Ovenseri-Ogbomo G, Ahaiwe K, Lewis OO, Echendu DC, et al. Assessment of knowledge, practice and guidelines towards the novel COVID-19 among eye care practitioners in Nigeria–a survey-based study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145141. [Article] [CAS] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Serwaa D, Lamptey E, Appiah AB, Senkyire EK, Ameyaw JK. Knowledge, risk perception and preparedness towards coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) outbreak among Ghanaians: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Supp 2). https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.22630.

-

Koh D, Lim MK, Chia SE, Ko SM, Qian F, Ng V, et al. Risk perception and impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on work and personal lives of healthcare Workers in Singapore What can we learn? Med Care. 2005;43(7):676–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000167181.36730.cc. [Article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

Dryhurst S, Schneider CR, Kerr J, Freeman ALJ, Recchia G, van der Bles AM, et al. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J Risk Res. 2020;23(7-8):994–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193. [Article] [Google Scholar]

-

Asefa A, Qanche Q, Hailemariam S, Dhuguma T, Nigussie T. Risk perception towards COVID-19 and its associated factors among waiters in selected towns of Southwest Ethiopia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:2601–10. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S276257. [Article] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Herrera-Diestra JL, Meyers LA. Local risk perception enhances epidemic control. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0225576. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225576. [Article] [CAS] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Ovenseri-Ogbomo G, Ishaya T, Osuagwu UL, Abu EK, Nwaeze O, Oloruntoba R, et al. Factors associated with the myth about 5G network during COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. J Glob Health Rep. 2020;4:1–13. https://doi.org/10.29392/001c.17606. [Article] [Google Scholar]

-

Lau JT, Tsui H, Lau M, Yang X. SARS transmission, risk factors, and prevention in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(4):587–92. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1004.030628. [Article] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [Article CAS] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Ferrer RA, Klein WM. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;5:85–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.012. [Article] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

-

Hjort J, Poulsen J. The arrival of fast internet and employment in Africa. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109(3):1032–79. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161385. [Article] [Google Scholar]